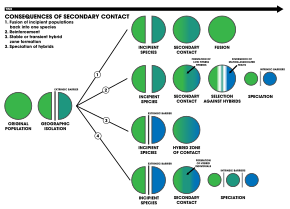

Secondary contact

Secondary contact is the process in which two allopatrically distributed populations of a species are geographically reunited.

This contact allows for the potential for the exchange of genes, dependent on how reproductively isolated the two populations have become.

For example, the secondary contact between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals, as well as the Denisovans, left traces of their genes in modern human.

Concerns have been raised that the homogenizing of the environment may contribute to more and more fusion, leading to the loss of biodiversity.

Because hybridization is costly (e.g. giving birth and raising a weak offspring), natural selection favors strong isolation mechanisms that can avoid such outcome, such as assortative mating.

1. An extrinsic barrier separates a species population into two but they come into contact before reproductive isolation is sufficient to result in speciation. The two populations fuse back into one species

2. Speciation by reinforcement

3. Two separated populations stay genetically distinct while hybrid swarms form in the zone of contact

4. Genome recombination results in speciation of the two populations, with an additional hybrid species . All three species are separated by intrinsic reproductive barriers [ 1 ]