European colonisation of Southeast Asia

Fiercely competitive, the Europeans soon sought to eliminate each other by forcibly taking control of the production centres, trade hubs and vital strategic locations, beginning with the Portuguese acquisition of Malacca in 1511.

[1] By the 19th century, all of Southeast Asia had been forced into the various spheres of influence of European global players except Siam, which had served as a convenient buffer state sandwiched between British Burma and French Indochina.

[2][3][4] The second phase of European colonisation of Southeast Asia is related to the Industrial Revolution and the rise of powerful nation states in Europe.

As the primary motivation for the first phase was the mere accumulation of wealth, the reasons for and degree of European interference during the second phase are dictated by geostrategic rivalries, the need to defend and grow spheres of interest, competition for commercial outlets, long term control of resources and the Southeast Asian economies becoming more closely tied to European industrial and financial affairs by the late 19th century.

[5][6] Advances in sciences, cartography, shipbuilding and navigation during the 15th to 17th centuries in Europe and tightening Turkish control and eventual shut down of the Eastern Mediterranean gateways into Asia first prompted Portuguese, and later Spanish and Dutch, sea voyagers to ship around Africa in search of new trading routes and business opportunities.

By 1498 Vasco da Gama, who had sailed round the Cape of Good Hope, established the first direct sea route from Europe to India.

[7] Central among the various plannings was to establish direct and permanent trade of the highly priced spices native to Southeast Asia, included pepper, cloves, nutmeg, mace and cinnamon.

An early form of the modern giant global corporations and the introduction of the stock market had trade volumes reach unprecedented levels.

Governmental support, military and administrative privileges, coining, legal and real estate rights enabled these enterprises to act as the official representatives of their country of origin in Southeast Asia.

[12][13] Initially, the British East India Company, led by Josiah Child, had little interest in or impact on the region, and were effectively expelled following the Siam–England war (1687).

Britain, in the guise of the British East India Company, turned their attention to the Bay of Bengal following the Peace with France and Spain (1783).

In 1786, the settlement of George Town was founded at the northeastern tip of Penang Island by Captain Francis Light, under the administration of Sir John Macpherson; this marked the beginning of British expansion into the Malay Peninsula.

Mutual economic dependence had become real by the 19th century, as Southeast Asia was now an integral provider of material and resources for the European economies.

To keep pace with surplus output, European manufacturers pushed the development of markets in new territories, such as Southeast Asia, which led to the next phase of establishing imperial rule.

The Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824 obligated the Dutch to ensure the safety of shipping and overland trade in and around Aceh, who accordingly sent the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army on the punitive expedition of 1831.

Only Siam managed to avoid direct foreign rule, although was compelled to political reforms and make generous concessions in order to appease the Western powers.

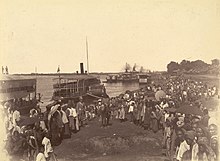

[19][20] By 1913, the British crown had occupied Burma, Malaya and the northern Borneo territories, the French controlled Indochina, the Dutch ruled the Netherlands East Indies while Portugal managed to hold on to Portuguese Timor.

One of these goals was expressed in the slogan, ‘The White Man's Burden’ (taken from a line in a poem by Rudyard Kipling), which was the mission to ‘civilise’ (uplift, advance) the ‘less fortunate’ and ‘less gifted’ people of Southeast Asia.

It expanded into Indochina in response to its need for international prestige to improve the government's image at home, and to keep abreast of other important European powers in terms of colonial acquisitions.

The early 20th century popular communist movement leaders of Vietnam were notably optimistic and “predicted a blessed future in which automobiles and trains would no longer be uniquely Western”, while Dutch author J.H.

[28][29] Increased labour demand resulted in mass immigration, especially from British India and China, which brought about massive demographic change.

Later on, more common features would emerge, such as the rise of nationalist movements, the Japanese occupation of Southeast Asia, and later the Cold War that engulfed many parts of the region.

Populations were then on the rise in order to meet demands for things like labor forces to create raw materials and industrial plants.

Siam's location on the map made it the perfect buffer zone between the French colony of Indochina and the British possessions on the Malay Peninsula.

The French and the British used maps to identify the areas they controlled, and when borders were unclear, they took advantage of the situation to lay claim to the region.

of Southeast Asia