Western literature

The later establishment of the medieval universities of Bologna, Padua, Vicenza, Naples, Salerno, Modena and Parma helped to spread culture and prepared the ground in which the new vernacular literature developed.

Scholasticism focused on preparing men to be doctors, lawyers or professional theologians, and was taught from approved textbooks in logic, natural philosophy, medicine, law and theology.

[38] Lorenzo de' Medici gave to his poetry the colors of the most pronounced realism as well as of the loftiest idealism, who passes from the Platonic sonnet to the impassioned triplets of the Amori di Venere, from the grandiosity of the Salve to Nencia and to Beoni, from the Canto carnascialesco to the lauda.

[52] His Storia d'Italia, which extends from the death of Lorenzo de' Medici to 1534, is full of political wisdom, is skillfully arranged in its parts, gives a lively picture of the character of the persons it treats of, and is written in a grand style.

[53][54] Inferior to them were Jacopo Nardi (a just and faithful historian and a virtuous man, who defended the rights of Florence against the Medici before Charles V), Benedetto Varchi, Giambattista Adriani, Bernardo Segni, and, outside Tuscany, Camillo Porzio, who related the Congiura de baroni and the history of Italy from 1547 to 1552; Angelo di Costanzo, Pietro Bembo, Paolo Paruta, and others.

[57] Prose and poetic literature within western regions, most prominently in England during the early modern era, had a distinct Biblical influence[3] which only began to be rejected during the Enlightenment period of the 18th century.

[60] These poets used wit and high intellectual standards while drawing from nature to reveal insights about emotion and rejected the romantic attributes of the Elizabethan period to birth a more analytical and introspective form of writing.

Marino and his followers mixed tradition and innovation: they worked with existing poetic forms, notably the sonnet, the sestina, the canzone, the madrigal, and less frequently the ottava rima, but developed new, more fluid structures and line lengths.

The passions, which had attracted the attention of Paduan writers and theorists in the mid-16th century as well as of Tasso, take centre stage, and are depicted in extreme forms in representations of subjects such as martyrdom, sacrifice, heroic grandeur, and abysmal existential fear.

The Marinists also take up new themes—notably the visual and musical arts and indoor scenes—with a new repertoire of references embracing modern scientific advances, other specialized branches of knowledge, and exotic locations and animals.

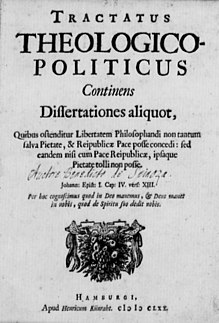

[73] Significant texts which shaped this literary period include Tractatus Theologico-Politicus, an anonymously published treatise in Amsterdam in which the author, Spinoza, rejected the Jewish and Christian religions for their lack of depth in teaching.

[75][76] Lodovico Antonio Muratori, after having collected in his Rerum Italicarum scriptores the chronicles, biographies, letters and diaries of Italian history from 500 to 1500, and having discussed the most obscure historical questions in the Antiquitates Italicae medii aevi, wrote the Annali d'Italia, minutely narrating facts derived from authentic sources.

Metastasio gave fresh expression to the affections, a natural turn to the dialogue and some interest to the plot; if he had not fallen into constant unnatural overrefinement and mawkishness, and into frequent anachronisms, he might have been considered the most important writer of opera seria libretti and the first dramatic reformer of the 18th century.

[83] In a collection of poems he published at twenty-three years of age, under the name of Ripano Eupilino, the poet shows his faculty of taking his scenes from real life, and in his satirical pieces he exhibits a spirit of outspoken opposition to his own times.

Love of liberty and desire for equality created a literature aimed at national objects, seeking to improve the condition of the country by freeing it from the double yoke of political and religious despotism.

[88] Vincenzo Monti was a patriot too, and wrote the Pellegrino apostolico, the Bassvilliana and the Feroniade; Napoleon's victories caused him to write the Prometeo and the Musagonia; in his Fanatismo and his Superstizione he attacked the papacy; afterwards he sang the praises of the Austrians.

The Lettere di Jacopo Ortis, inspired by Goethe's The Sorrows of Young Werther, are a love story with a mixture of patriotism; they contain a violent protest against the Treaty of Campo Formio, and an outburst from Foscolo's own heart about an unhappy love-affair of his.

[92] Pieces by authors including Marie-Antoinette Lenoir, Louise d'Épinay and Anne-Thérèse de Lambert all shared the same role of shaping young French women to lead successful and progressive lives.

The romantic school had as its organ the Conciliatore established in 1818 at Milan, on the staff of which were Silvio Pellico, Ludovico di Breme, Giovile Scalvini, Tommaso Grossi, Giovanni Berchet, Samuele Biava, and Alessandro Manzoni.

[5] The desire for freedom and the sense of "national redemption" is reflected heavily in the works of Italian Romantics, including Ugo Foscolo, who wrote the story The Last Letters of Jacopo Ortis, in which a man was forced to commit suicide due to the political persecutions of his country.

In his Operette Morali—dialogues and discourses marked by a cold and bitter smile at human destinies that freezes the reader—the clearness of style, the simplicity of language and the depth of conception are such that perhaps he is not only the greatest lyrical poet since Dante, but also one of the most perfect writers of prose that Italian literature has had.

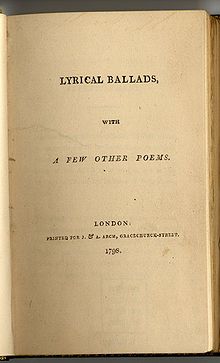

[citation needed] British 19th-century Romanticism developed literature which focused on the "self-organisation of living beings, their growth and adaption into their environments and the creative spark that inspired the physical system to perform complex functions".

The first trend is the Scapigliatura, that attempted to rejuvenate Italian culture through foreign influences, notably from the poetry of Charles Baudelaire and the works of American writer Edgar Allan Poe.

The second trend is represented by Giosuè Carducci, a dominant figure of this period, fiery opponent of the Romantics and restorer of the ancient metres and spirit who, great as a poet, was scarcely less distinguished as a literary critic and historian.

Olindo Guerrini (who wrote under the pseudonym of Lorenzo Stecchetti) is the chief representative of verismo in poetry, and, though his early works obtained a succès de scandale, he is the author of many lyrics of intrinsic value.

Moravia wrote the novels The Conformist (1951) and La Ciociara (1957), while The Moon and the Bonfires (1949) became Pavese's most recognized work; Primo Levi documented his experiences in Auschwitz in If This Is a Man (1947); among the other writers were Carlo Levi, who reflected the experience of political exile in southern Italy in Christ Stopped at Eboli (1951); Curzio Malaparte, author of Kaputt (1944) and The Skin (1949), novels dealing with the war on the Eastern Front and in Naples; Pier Paolo Pasolini, also a poet and a film director, who described the life of the Roman lumpenproletariat in The Ragazzi (1955);[127][128] and Corrado Alvaro.

Italo Calvino also ventured into fantasy in the trilogy I nostri antenati (Our Ancestors, 1952–1959) and post-modernism in the novel Se una notte d'inverno un viaggiatore... (If on a Winter's Night a Traveller, 1979).

[129] Leonardo Sciascia came to public attention with his novel Il giorno della civetta (The Day of the Owl, 1961), exposing the extent of Mafia corruption in modern Sicilian society.

In the 20th century, Italian children's literature was represented by such writers as Gianni Rodari, author of Il romanzo di Cipollino, and Nicoletta Costa, creator of Julian Rabbit and Olga the Cloud.

[138][139] Early Italian humanism, which in many respects continued the grammatical and rhetorical traditions of the Middle Ages, not merely provided the old Trivium with a new and more ambitious name (Studia humanitatis), but also increased its actual scope, content and significance in the curriculum of the schools and universities and in its own extensive literary production.