Fallingwater

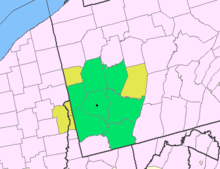

Fallingwater is situated in Stewart Township in the Laurel Highlands of southwestern Pennsylvania, United States,[4][5] about 72 miles (116 km) southeast of Pittsburgh.

[11] Nearby are the Bear Run Natural Area to the north, as well as Ohiopyle State Park[12][13] and Fort Necessity National Battlefield to the south.

[47] In 1922, Edgar and his wife Liliane built a simple summer cabin on a nearby cliff, which was nicknamed the "Hangover" and lacked electricity, plumbing, or heating.

[73][74] Wright's apprentices Edgar Tafel and Robert Mosher were the most heavily involved in the building's design, while his employees Mendel Glickman and William Wesley Peters were the structural engineers.

[78][80] Contrary to common claims that Wright had ignored the design for nine months before hurriedly sketching it, he had already devised the plans mentally[73][74][81] and had written about them to Edgar Sr. multiple times.

[84][85] The house was to be placed on Bear Run's northern bank, oriented 30 degrees counterclockwise from due south, so that every room would receive natural light.

[111] Edgar Jr. was heavily involved with the project and acted as an intermediary between his father and Wright,[112] and several Kaufmann's employees and extended family members also worked on site.

[108] A disused rock quarry nearby was reopened in late 1935 to provide stone for the house,[92][93][106] although actual work on the foundation did not begin until April 1936.

[109] The masonry contractor, Norbert James Zeller, began building the house's access bridge shortly thereafter; he was later fired following disputes with Wright and Kaufmann.

[92][127][128] Wright rejected these plans because he believed the extra steel would overload the terraces,[129][130] and he also dismissed the idea of constructing additional supports in Bear Run's streambed.

[129] Glickman, contacted by Mosher, reportedly confessed that he had forgotten to account for the compressive forces of the concrete beams,[140][129] though the historian Franklin Toker disputes that this happened.

[153] Wright reportedly decided on the final color, a shade of ocher, after picking up a dried rhododendron leaf;[154] he ordered waterproof paint from DuPont.

[149][153] At Kaufmann's request, Wright added a plunge pool at the bottom of the living-room stairs, and he retained the large boulder on the living room's floor.

[7][248] The Getty Foundation provided the WPC with a $70,000 grant to investigate the structural issues,[137] and Fallingwater received approximately $900,000 through the federal Save America's Treasures program.

[128][233] The WPC also planned to strengthen one of the terraces using carbon fiber, rebuild the staircase from the living room to Bear Run, and repair water damage.

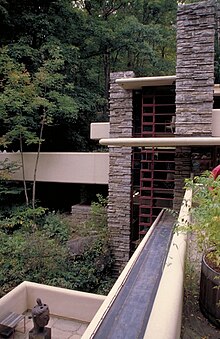

[279][280] Though the house is also sometimes described as a Modern–styled building, The Wall Street Journal wrote that the design was "a kind of streamlined, handmade, organic architecture" not emulated by other architects.

[87][321] Wright, who was 5 ft 8 in (1.73 m) tall, designed the house based on the assumption that the average person was his height, so some ceilings are as low as 6 feet 4 inches (1.93 m).

[160] Some interior design elements (such as furniture, shelves, and the beam on which the kitchen kettle is hung) are cantilevered,[205][292] while others (including niches and stairs) incorporate circular arcs.

[23][327] The master bedroom has custom movable shelves and bedside lighting,[63] glass doors to the master-bedroom terrace,[315] and an ornate fireplace mantel with three large rocks.

[63] On the third floor is a dead-end gallery, which was originally intended to connect with the footbridge over the driveway,[172][342] but instead functioned as a bedroom for Edgar Jr.[342] A set of stairs descends to the western second-story terrace.

[54] Liliane's bedroom features a niche with a wooden sculpture of Madonna and Child, which was carved c. 1420,[54][367] while Edgar Sr.'s room includes two busts by Richmond Barthé.

The guesthouse includes woodblock prints and an 1877 landscape painting by José María Velasco Gómez, while the guest wing's pool has an abstract sculpture by Peter Voulkos.

[281] Fallingwater continued to record nearly 130,000 annual visitors through the 1990s,[300] and an Associated Press article from 1999 estimated that over 2.7 million people had visited the building ever since it opened to the public.

[388] A writer for The Christian Science Monitor in 1938 wrote that the use of contrasting materials, shapes, and tones "add so much enchantment to the interior",[289] while Time called Fallingwater Wright's "most beautiful job".

[115] A Baltimore Sun writer, in 1981, praised both the house's architecture and furnishings, regarding the Kaufmanns' possessions as giving Fallingwater a homey feel.

[398] The Patriot-News said that Fallingwater retained the character of a mountain lodge,[101] and Thomas Hine of The Philadelphia Inquirer regarded the house as being simultaneously comfortable and rustic.

[205][288] The Hartford Courant said that, despite mixed reviews of Wright's design philosophy, the house itself "feels organic and inevitable",[154] and The Guardian said that Fallingwater combined the natural environment and modern-style architecture.

[91] David Taylor of The Washington Post said the design "gives fresh meaning to the phrase 'living on the land'",[81] while Americas magazine called the house "a universal icon of the persistent effort to achieve harmony with nature".

[144] The house gained more prominence in early 1938 following a MoMA exhibition and extensive media coverage,[5][17][423] particularly in publications controlled by Henry Luce and William Randolph Hearst.

[384][446] UNESCO ultimately added eight properties, including Fallingwater, to the World Heritage List in July 2019 under the title "The 20th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright".