Fascism and ideology

[14] Hitler focused on ancient Rome during its rise to dominance and at the height of its power as a model to follow, and he deeply admired the Roman Empire for its ability to forge a strong and unified civilization.

[24] The fin-de-siècle intellectual school of the 1890s – including Gabriele d'Annunzio and Enrico Corradini in Italy; Maurice Barrès, Edouard Drumont and Georges Sorel in France; and Paul de Lagarde, Julius Langbehn and Arthur Moeller van den Bruck in Germany – saw social and political collectivity as more important than individualism and rationalism.

[24] The fin-de-siècle outlook was influenced by various intellectual developments, including Darwinian biology; Wagnerian aesthetics; Arthur de Gobineau's racialism; Gustave Le Bon's psychology; and the philosophies of Friedrich Nietzsche, Fyodor Dostoyevsky and Henri Bergson.

[24] Nietzsche's argument that "God is dead" coincided with his attack on the "herd mentality" of Christianity, democracy and modern collectivism; his concept of the Übermensch; and his advocacy of the will to power as a primordial instinct were major influences upon many of the fin-de-siècle generation.

[40] He emphasized class collaboration, the role of intuition and emotion in politics alongside racial Antisemitism, and "he tried to combine the search for energy and a vital style of life with national rootedness and a sort of Darwinian racism.

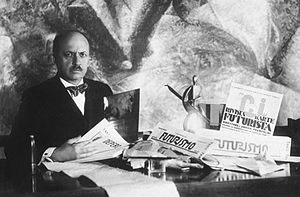

[42] One of the key persons who greatly influenced fascism was the French intellectual Georges Sorel, who "must be considered one of the least classifiable political thinkers of the twentieth century" and supported a variety of different ideologies throughout his life, including conservatism, socialism, revolutionary syndicalism and nationalism.

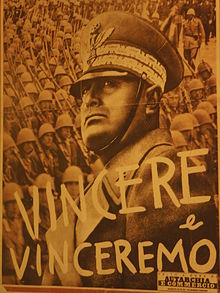

[58] Italian national syndicalists held a common set of principles: the rejection of bourgeois values, democracy, liberalism, Marxism, internationalism and pacifism and the promotion of heroism, vitalism and violence.

[66] At first, these interventionist groups were composed of disaffected syndicalists who had concluded that their attempts to promote social change through a general strike had been a failure, and became interested in the transformative potential of militarism and war.

The revolution in Russia gave rise to a fear of communism among the elites and among society at large in several European countries, and fascist movements gained support by presenting themselves as a radical anti-communist political force.

He admired Lenin's boldness in seizing power by force and was envious of the success of the Bolsheviks, while at the same time attacking them in his paper for restricting free speech and creating "a tyranny worse than that of the tsars.

In a speech delivered in Milan's Piazza San Sepolcro in March 1919, Mussolini set forward the proposals of the new movement, combining ideas from nationalism, Sorelian syndicalism, the idealism of the French philosopher Henri Bergson, and the theories of Gaetano Mosca and Vilfredo Pareto.

[88] Nevertheless, Mussolini also demanded the expansion of Italian territories, particularly by annexing Dalmatia (which he claimed could be accomplished by peaceful means), and insisted that "the state must confine itself to directing the civil and political life of the nation," which meant taking the government out of business and transferring large segments of the economy from public to private control.

Soon, agrarian conflicts in the region of Emilia and in the Po Valley provided an opportunity to launch a series of violent attacks against the socialists, and thus to win credibility with the conservatives and establish fascism as a paramilitary movement rather than an electoral one.

[100] Together with many smaller donations that he received from the public as part of a fund drive to support D'Annunzio, this helped to build up the Fascist movement and transform it from a small group based around Milan to a national political force.

[100] Mussolini organized his own militia, known as the "blackshirts," which started a campaign of violence against Communists, Socialists, trade unions and co-operatives under the pretense of "saving the country from bolshevism" and preserving order and internal peace in Italy.

[114] Some political organizations, such as the conservative Italian Nationalist Association, "assured King Victor Emmanuel that their own Sempre Pronti militia was ready to fight the Blackshirts" if they entered Rome, but their offer was never accepted.

[120] The Fascists began their attempt to entrench Fascism in Italy with the Acerbo Law, which guaranteed a plurality of the seats in parliament to any party or coalition list in an election that received 25% or more of the vote.

He attempted to entrench his Party of National Unity throughout the country, created a youth organization and a political militia with sixty thousand members, promoted social reforms such as a 48-hour workweek in industry, and pursued irredentist claims on Hungary's neighbors.

By 1943, after Italy faced multiple military failures, complete reliance and subordination to Germany and an Allied invasion, Mussolini was removed as head of government and arrested by the order of King Victor Emmanuel III.

[181] The affinity shown by some neo-Nazis to the leftist-oriented Syrian Ba'ath party is commonly explained as part of the former's far-right worldview rooted in Islamophobia, admiration for totalitarian states and perception that the Ba'athist government is against Jews.

[208] The economic policies of fascist governments, meanwhile, were generally not based on ideological commitments one way or the other, instead being dictated by pragmatic concerns with building a strong national economy, promoting autarky, and the need to prepare for and to wage war.

[216] Yet Mussolini at the same time promised to eliminate state intervention in business and to transfer large segments of the economy from public to private control,[89] and the fascists met in a hall provided by Milanese businessmen.

[107] Mussolini appealed to conservative liberals to support a future fascist seizure of power by arguing that "capitalism would flourish best if Italy discarded democracy and accepted dictatorship as necessary in order to crush socialism and make government effective.

[230][231] He claimed that supercapitalism had resulted in the collapse of the capitalist system in the Great Depression,[232] but that the industrial developments of earlier types of capitalism were valuable and that private property should be supported as long as it was productive.

[285] Although Fascism sought to "destroy the existing political order", it had tentatively adopted the economic elements of liberalism, but "completely denied its philosophical principles and the intellectual and moral heritage of modernity".

They took a stance against unemployment benefits upon coming to power in 1922,[227] but later argued that improving the well-being of the labor force could serve the national interest by increasing productive potential, and adopted welfare measures on this basis.

"[297] Out of a "determination to make Italy the powerful, modern state of his imagination," Mussolini also began a broad campaign of public works after 1925, such that "bridges, canals, and roads were built, hospitals and schools, railway stations and orphanages; swamps were drained and land reclaimed, forests were planted and universities were endowed".

"[305] Fascism is historically strongly opposed to socialism and communism, due to their support of class revolution as well as "decadent" values, including internationalism, egalitarianism, horizontal collectivism, materialism and cosmopolitanism.

[324] Fascists see themselves as supporting a moral and spiritual renewal based on a warlike spirit of violence and heroism, and they condemn democratic socialism for advocating "humanistic lachrimosity" such as natural rights, justice, and equality.

[327] Benito Mussolini mentioned revolutionary syndicalist Georges Sorel – along with Hubert Lagardelle and his journal Le Mouvement socialiste, which advocated a technocratic vision of society – as major influences on fascism.