Coverture

Coverture was first substantially modified by late-19th-century Married Women's Property Acts passed in various common-law jurisdictions, and was weakened and eventually eliminated by later reforms.

Upon this principle, of a union of person in husband and wife, depend almost all the legal rights, duties, and disabilities, that either of them acquire by the marriage.

"[3] A married woman could not own property, sign legal documents or enter into a contract, obtain an education against her husband's wishes, or keep a salary for herself.

[7] Collectively, many of these studies have argued that 'there has been a tendency to overplay the extent to which coverture applied', as legal records reveal that married women could possess rights over property, could take part in business transactions, and interact with the courts.

Married women were responsible for their own actions in criminal presentments and defamation, but their husbands represented them in litigation for abduction and in interpersonal pleas.

[10] The custom is known to have been adopted in a number of other towns, including Bristol, Lincoln, York, Sandwich, Rye, Carlisle, Chester and Exeter.

[13] According to Chernock, "coverture, ... [a 1777] author ... concluded, was the product of foreign Norman invasion in the eleventh century—not, as Blackstone would have it, a time-tested 'English' legal practice.

The way in which coverture operated across the common law world has been the subject of recent studies examining the subordinating effects of marriage for women across medieval and early modern England and North America, in a variety of legal contexts.

[17] It has been argued that in practice, most of the rules of coverture "served not to guide every transaction but rather to provide clarity and direction in times of crisis or death.

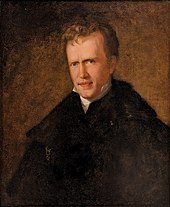

"[21] Chernock claimed that "as the editor of Blackstone's Commentaries, [Edward] Christian used his popular thirteenth edition, published in 1800, to highlight the ways in which the practice of coverture might be modified.

"[16] Chernock wrote that "Christian ... proceeded to recommend that a husband cease to be 'absolutely master of the profits of the wife's lands during the coverture.

[23] The earliest American women's rights lecturer, John Neal[24][25] attacked coverture in speeches and public debates as early as 1823,[26] but most prominently in the 1840s,[27] asking "how long [women] shall be rendered by law incapable of acquiring, holding, or transmitting property, except under special conditions, like the slave?

"[26] In the 1850s, according to DuBois, Lucy Stone criticized "the common law of marriage because it 'gives the "custody" of the wife's person to her husband, so that he has a right to her even against herself.

"[30] Chernock continued, "for those who determined that legal reforms were the key to achieving a more enlightened relationship between the sexes, coverture was a primary object of attention.

[33] In the mid-19th century, according to Melissa J. Homestead, coverture was criticized as depriving married women authors of the financial benefits of their copyrights,[34] including analogizing to slavery; one woman poet "explicitly analogized her legal status as a married woman author to that of an American slave.

[36] Hendrik Hartog counter-criticized that coverture was only a legal fiction and not descriptive of social reality[37] and that courts applying equity jurisdiction had developed many exceptions to coverture,[38] but, according to Norma Basch, the exceptions themselves still required that the woman be dependent on someone[39] and not all agreements between spouses to let wives control their property were enforceable in court.

[43] According to Canaday, "coverture was diminished ... in the 1970s, as part of a broader feminist revolution in law that further weakened the principle that a husband owned a wife's labor (including her person). ...

[49] This situation continued until the mid-to-late 19th century, when married women's property acts started to be passed in many English-speaking jurisdictions, setting the stage for further reforms.

[52] The abolition of coverture has been seen as "one of the greatest extensions of property rights in human history", and one that led to a number of positive financial and economic impacts.

Specifically, it led to shifts in household portfolios, a positive shock to the supply of credit, and a reallocation of labor towards non-agriculture and capital intensive industries.

[53] As recently as 1972, two US states allowed a wife accused in criminal court to offer as a legal defense that she was obeying her husband's orders.

[58] Neighboring Switzerland was one of the last European countries to establish gender equality in marriage: married women's rights were severely restricted until 1988, when legal reforms providing gender equality in marriage, abolishing the legal authority of the husband, came into force (these reforms had been approved in 1985 in a referendum, with 54.7% votes in favor).