Total fertility rate

The total fertility rate (TFR) of a population is the average number of children that are born to a woman over her lifetime, if they were to experience the exact current age-specific fertility rates (ASFRs) through their lifetime, and they were to live from birth until the end of their reproductive life.

Historically, developed countries have significantly lower fertility rates, generally correlated with greater wealth, education, urbanization, and other factors.

[1] The United Nations predicts that global fertility will continue to decline for the remainder of this century and reach a below-replacement level of 1.8 by 2100, and that world population will peak in 2084.

Instead, the TFR is based on the age-specific fertility rates of women in their "child-bearing years," typically considered to be ages 15–44 in international statistical usage.

The NRR is not as commonly used as the TFR, but it is particularly relevant in cases where the number of male babies born is very high due to gender imbalance and sex selection.

In other words, the TPFR is a misleading measure of life cycle fertility when childbearing age is changing, due to this statistical artifact.

At the left side is shown the empirical relation between the two variables in a cross-section of countries with the most recent y-y growth rate.

[citation needed] Factors generally associated with increased fertility include the intention to have children, very high level of gender inequality, inter-generational transmission of values, marriage and cohabitation, maternal and social support, rural residence, pro family government programs, low IQ and increased food production.

[citation needed] Factors generally associated with decreased fertility include rising income, value and attitude changes, education, female labor participation, population control, age, contraception, partner reluctance to having children, a low level of gender inequality, and infertility.

The effect of all these factors can be summarized with a plot of total fertility rate against Human Development Index (HDI) for a sample of countries.

The chart shows that the two factors are inversely correlated, that is, in general, the lower a country's HDI the higher its fertility.

[citation needed] Another common way of summarizing the relationship between economic development and fertility is a plot of TFR against per capita GDP, a proxy for standard of living.

[citation needed] The impact of human development on TFR can best be summarized by a quote from Karan Singh, a former minister of population in India.

The inverse relationship between income and fertility has been termed a demographic-economic paradox because evolutionary biology suggests that greater means should enable the production of more offspring, not fewer.

For instance, Scandinavian countries and France are among the least religious in the EU, but have the highest TFR, while the opposite is true about Portugal, Greece, Cyprus, Poland and Spain.

[22] Conversely, in China the government sought to lower the fertility rate, and, as such, enacted the one-child policy (1978–2015), which included abuses such as forced abortions.

Such policies were carried out against ethnic minorities in Europe and North America in the first half of the 20th century, and more recently in Latin America against the Indigenous population in the 1990s; in Peru, former President Alberto Fujimori has been accused of genocide and crimes against humanity as a result of a sterilization program put in place by his administration targeting indigenous people (mainly the Quechua and Aymara people).

[25] From around 10,000 BC to the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, fertility rates around the world were high by 21st-century standards, ranging from 4.5 to 7.5 children per woman.[2]76-77,.

[2] 76-77 Child mortality could reach 50%[27] and that plus the need to produce workers, male heirs, and old-age caregivers required a high fertility rate by 21st-century standards.

[29] After 1800, the Industrial Revolution began in some places, particularly Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, and they underwent the beginnings of what is now called the demographic transition.

Stage two of this process fueled a steady reduction in mortality rates due to improvements in public sanitation, personal hygiene and the food supply, which reduced the number of famines.

[34] The average fertility rate in countries such as Thailand[35] or Chile[36] approached the mark of one child per woman, which triggered concerns about the rapid aging of populations worldwide.

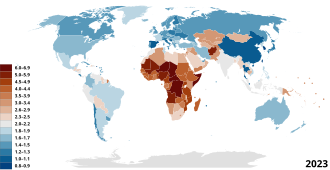

[34] The table[37] shows that after 1965, the demographic transition spread around the world, and the global TFR began a long decline that continues in the 21st century.

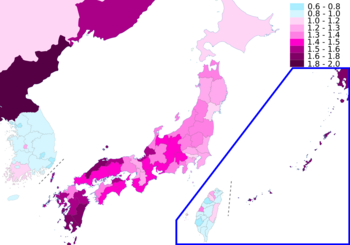

[39] Hong Kong, Macau, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan have the lowest-low fertility, defined as TFR at or below 1.3, and are among the lowest in the world.

In July 2021, a three-child policy was introduced, as China's population is aging faster than almost any other country in modern history.

[43] Japan's population is rapidly aging due to both a long life expectancy and a low birth rate.

[45] Rising housing expenses, shrinking job opportunities for younger generations, insufficient support to families with newborns either from the government or employers are among the major explanations for its crawling TFR, which fell to 0.92 in 2019.

[46] Koreans are yet to find viable solutions to make the birthrate rebound, even after trying out dozens of programs over a decade, including subsidizing rearing expenses, giving priorities for public rental housing to couples with multiple children, funding day care centers, reserving seats in public transportation for pregnant women, and so on.

In 2021 estimates for the non-EU European post-Soviet states group, Russia had a TFR of 1.60, Moldova 1.59, Ukraine 1.57, and Belarus 1.52.

However, the fertility rate of immigrants to the US has been found to decrease sharply in the second generation, correlating with improved education and income.