First Australian Imperial Force

It was formed as the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) following Britain's declaration of war on Germany on 15 August 1914, with an initial strength of one infantry division and one light horse brigade.

[2] The Australian government pledged to supply 20,000 men organised as one infantry division and one light horse brigade plus supporting units, for service "wherever the British desired", in keeping with pre-war Imperial defence planning.

[17] Predominantly a fighting force based on infantry battalions and light horse regiments—the high proportion of close combat troops to support personnel (e.g. medical, administrative, logistic, etc.)

[20] However, the AIF mainly relied on the British Army for medium and heavy artillery support and other weapons systems necessary for combined arms warfare that were developed later in the war, including aircraft and tanks.

These shortages were unable to be rectified prior to the landing at Gallipoli where the howitzers would have provided the plunging and high-angled fire that was required due to the rough terrain at Anzac Cove.

[59] The following corps-level formations were raised:[60] The Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) was formed from the AIF and NZEF in preparation for the Gallipoli Campaign in 1915 and was commanded by Birdwood.

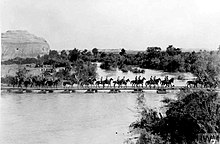

[64] Meanwhile, the majority of the Australian Light Horse had remained in the Middle East and subsequently served in Egypt, Sinai, Palestine and Syria with the Desert Column of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force.

[80] Although operationally placed at the disposal of the British, the AIF was administered as a separate national force, with the Australian government reserving the responsibility for the promotion, pay, clothing, equipment and feeding of its personnel.

[81] The AIF was administered separately from the home-based army in Australia, and a parallel system was set up to deal with non-operational matters including record-keeping, finance, ordnance, personnel, quartermaster and other issues.

[100][Note 6] Approximately 18 percent of those who served in the AIF had been born in the United Kingdom, marginally more than their proportion of the Australian population,[103] although almost all enlistments occurred in Australia, with only 57 people being recruited from overseas.

[115] From then a gradual decline occurred,[116] and whereas news from Gallipoli had increased recruitment, the fighting at Fromelles and Pozieres did not have a similar effect, with monthly totals dropping from 10,656 in May 1916 to around 6,000 between June and August.

[119] Monthly intakes fell further in early 1918, but peaked in May (4,888) and remained relatively steady albeit reduced from previous periods, before slightly increasing in October (3,619) prior to the armistice in November.

Battle hardened and experienced as a result, this fact partially explains the important role the AIF subsequently played in the final defeat of the German Army in 1918.

[46] Reflecting the progressive nature of Australian industrial and social policy of the era, this rate of pay was intended to be equal to that of the average worker (after including rations and accommodation) and higher than that of soldiers in the Militia.

[133] While the AIF's initial senior officers had been members of the pre-war military, few had any substantial experience in managing brigade-sized or larger units in the field as training exercises on this scale had been rarely conducted before the outbreak of hostilities.

These formations were later sent to the United Kingdom and were absorbed into a large system of depots that was established on Salisbury Plain by each branch of the AIF including infantry, engineers, artillery, signals, medical and logistics.

[135][136] Like the British Army, the AIF sought to rapidly pass on "lessons learned" as the war progressed, and these were widely transmitted through regularly updated training documents.

[147] Historian Peter Stanley has written that "the AIF was, paradoxically, both a cohesive and remarkably effective force, but also one whose members could not be relied upon to accept military discipline or to even remain in action".

[145] Indiscipline, misbehaviour, and public drunkenness were reportedly widespread in Egypt in 1914–15, while a number of AIF personnel were also involved in several civil disturbances or riots in the red-light district of Cairo during this period.

This may be partially explained by the refusal of the Australian government to follow the British Army practice of applying the death penalty to desertion, unlike New Zealand or Canada, as well as to the high proportion of front-line personnel in the AIF.

Approximately three-quarters of AIF volunteers were members of the working class, with a high proportion also being trade unionists, and soldiers frequently applied their attitudes to industrial relations to the Army.

[158] Historian Nathan Wise has judged that the frequent use of industrial action in the AIF led to improved conditions for the soldiers, and contributed to it having a less strict military culture than was common in the British Army.

[168] The Australians first saw combat during the Senussi Uprising in the Libyan Desert and the Nile Valley, during which the combined British forces successfully put down the primitive pro-Turkish Islamic sect with heavy casualties.

[170] Following this victory the British forces went on the offensive in the Sinai, although the pace of the advance was governed by the speed by which the railway and water pipeline could be constructed from the Suez Canal.

[176] I ANZAC Corps subsequently took up positions in a quiet sector south of Armentières on 7 April 1916 and for the next two and a half years the AIF participated in most of the major battles on the Western Front, earning a formidable reputation.

[194] The offensive continued for four months, and during the Second Battle of the Somme the Australian Corps fought actions at Lihons, Etinehem, Proyart, Chuignes, and Mont St Quentin, before their final engagement of the war on 5 October 1918 at Montbrehain.

[196] The AIF was withdrawn for rest and reorganisation following the engagement at Montbrehain; at this time the Australian Corps appeared to be close to breaking as a result of its heavy casualties since August.

As part of the "Anzac legend", the soldiers were depicted as good humoured and egalitarian men who had little time for the formalities of military life or strict discipline, yet fought fiercely and skilfully in battle.

Yet many of the factors which had resulted in the AIF's success as a military formation were not exclusively Australian, with most modern armies recognising the importance of small-unit identity and group cohesion in maintaining morale.

During the 1950s and 1960s social critics began to associate the "Anzac legend" with complacency and conformism, and popular discontent concerning the Vietnam War and conscription from the mid-1960s led many people to reject it.

![Black and white group portrait of a group of men wearing suits seated and standing in front of two banners. Both banners read "We are the recruits for the A.I.F. from Central Q'Land [Queensland] will you join us?" in block letters.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/95/AIF_recruits_from_Rockhampton_and_district_at_Brisbane_in_1915_or_1916_-_adjusted.jpg/220px-AIF_recruits_from_Rockhampton_and_district_at_Brisbane_in_1915_or_1916_-_adjusted.jpg)