Fixed stars

This is in contrast to those lights visible to naked eye, namely planets and comets, that appear to move slowly among those "fixed" stars.

Due to their star-like appearance when viewed with the naked eye, the few visible individual nebulae and other deep-sky objects also are counted among the fixed stars.

Due to their immense distance from Earth, these objects appear to move so slowly in the sky that the change in their relative positions is nearly imperceptible on human timescales, except under careful examination with modern instruments, such as telescopes, that can reveal their proper motions.

In the astronomical tradition of Aristotelian physics which spanned from ancient Greece to early scientific Europe, the fixed stars were believed to exist attached on a giant celestial sphere, or firmament, which revolves daily around Earth.

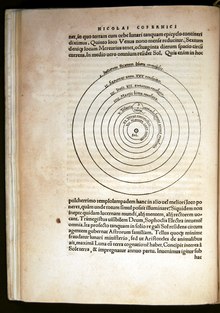

The Copernican Revolution of the 1540s fueled the idea held by some philosophers in ancient Greece and the Islamic world that stars were actually other suns, possibly with their own planets.

People in many cultures have imagined that the brightest stars form constellations, which are apparent pictures in the sky seeming to be persistent, being deemed also as fixed.

He writes in On the Heavens, "If the bodies of the stars moved in a quantity either of air or of fire...the noise which they created would inevitably be tremendous, and this being so, it would reach and shatter things here on earth".

This system presented two more unique ideas in addition to being heliocentric: the Earth rotated daily to create day, night, and the perceived motions of the other heavenly bodies, and the sphere of fixed stars at its boundary were immensely distant from its center.

[10] Ptolemy used and wrote about the geocentric system, drawing greatly on traditional Aristotelian physics,[10] but using more complicated devices, known as deferent and epicycles he borrowed from previous works by geometer Apollonius of Perga and astronomer Hipparchus of Nicaea.

[12] His model was not widely accepted, despite his authority; he was one of the earliest developers of the system of the seven liberal arts, the trivium (grammar, logic, and rhetoric) and the quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, music, astronomy), that structured early medieval education.

[10] Kepler's laws were the tipping point in finally disproving the old geocentric (or Ptolemaic) cosmic theories and models,[18] what was backed by the first uses of telescope by his contemporary Galileo Galilei, also an advocate of Copernicus.

[20] Nonetheless, later Pythagorians as Philolaus around 400 BC, also conceived a universe with orbiting bodies,[21] thus assuming the fixed stars were, at least, a bit farther than the Moon, the Sun and the rest of the planets.

[23] As far as the Sun and the Moon were conceived as spherical bodies, and as they do not collide at solar eclipses, this implies than the outer space should have some certain, indeterminate, depth.

Eudoxus of Cnidus, in around 380 BC, devised a geometric-mathematical model for the movements of the planets based on (conceptual) concentric spheres centered on Earth,[24] and by 360 BC Plato claimed in his Timaeus that circles and spheres were the preferred shape of the universe, and that the Earth was at the centre and the stars forming the outermost shell, followed by planets, the Sun, and the Moon.

By all these devices, and even assuming the planets were star-like, single points, the sphere of the fixed stars should implicitly be farther than previously thought.

[28] This reasoning led him to assert that, as stars do not show evident parallax viewed from Earth along a single year, they must be very, very far away from the terrestrial surface and, assuming they were all at the same distance from us, he gave a relative estimation.

Following the heliocentric ideas of Aristarcus (but not explicitly supporting them), around 250 BC Archimedes in his work The Sand Reckoner computes the diameter of the universe centered around the Sun to be about 10×1014 stadia (in modern units, about 2 light years, 18.93×1012 km, 11.76×1012 mi).

[30]Around 210 BC, Apollonius of Perga shows the equivalence of two descriptions of the apparent retrograde motions of planets (assuming the geocentric model): one using eccentrics and another deferent and epicycles.

1/3 Earth radius), plus the width of the Sun (it being, at least, the same that the Moon), plus the indeterminate thickness of the planets' spheres (believed to be thin, anyway), for a total about 386,400 km (240,100 mi).

[36] But by the European Renaissance, the possibility that such a huge sphere could complete a single revolution of 360° around the Earth in only 24 hours was deemed improbable,[37] and this point was one of the arguments of Nicholas Copernicus for leaving behind the centuries-old geocentric model.

The highest upper bound ever given was by Jewish astronomer Levi ben Gershon (Gersonides) who, circa 1300, estimated the distance to the fixed stars to be no less than 159,651,513,380,944 Earth radii, or about 100,000 light-years in modern units.

Other cultures contributed to thought about the fixed stars including the Babylonians, who from the eighteenth to the sixth century BC constructed constellation maps.

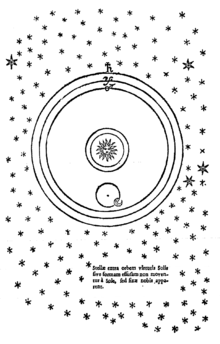

[42] All other later models of the planetary system show a celestial sphere containing fixed stars on the outermost part of the universe, its edge, within it lie all the rest of the moving luminaires.

[10] He continued to examine the skies and constellations and soon knew that the "fixed stars" which had been studied and mapped were only a tiny portion of the massive universe that lay beyond the reach of the naked eye.

[10] When in 1610 he aimed his telescope to the faint strip of the Milky Way, he found it resolves into countless white star-like spots, presumably farther stars themselves.

[48] By then it had been established beyond doubt, thanks to increased telescopic observations plus Keplerian and Newtonian celestial mechanics, that planets are other worlds, and stars are other distant suns, so the whole Solar System is actually only a small part of an immensely large universe, and definitively something distinct.

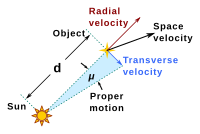

One group contained the fixed stars, which appear to rise and set but keep the same relative arrangement over time, and show no evident stellar parallax, which is a change in apparent position caused by the orbital motion of the Earth.

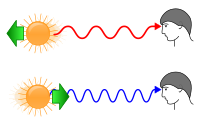

William Huggins ventured in 1868 to estimate the radial velocity of Sirius with respect to the Sun, based on observed redshift of the star's light.

Mach would criticize Newton's concept of absolute acceleration, stating that the shape of the water only proves the rotation with respect to the rest of the universe.

However, these attempts led to many opposing concepts to inertia that were not supported, to which many agreed that the basic premise of Newtonian kinetic energy should be preserved.