Fort York

[3] In the early 1790s, John Graves Simcoe, the lieutenant governor of Upper Canada, began to consider building a fort in Toronto; as a part of a larger effort to reposition isolated British garrisons in the U.S. Northwest Territory and near the Canada–United States border to more centralized positions, and to vacate British forces from U.S. territory in an attempt to reduce tensions with the Americans.

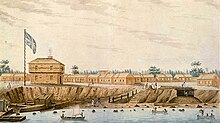

[5] Simcoe selected Toronto (renamed York from 1793 to 1834) as the location of a new military garrison, due to its proximity away from the border, and because its natural harbour only had one access point from water, making it easy to defend.

[5][note 2] Once established, Simcoe envisioned the harbour as a base where British control over Lake Ontario could be exerted, and where they could repel a potential American attack from the west into eastern Upper Canada.

[4] However, his proposal to further fortify the settlement was rejected by the governor general of the Canadas, Lord Dorchester, who took the position that the money should instead be spent on improving the defences at the naval base in Kingston.

[6] Over the next year, the Queen's Rangers erected a guard house, and two blockhouses near Gibraltar Point, albeit at a smaller scale than what was envisioned by Simcoe.

[9] In 1794, Simcoe took several artillery pieces from these fortifications after he was ordered to erect Fort Miamis in the Northwest Territory, leaving York with only a few condemned guns that were taken from Kingston.

Many of its original structures were also replaced with new buildings, including barracks, carriage and engine shed, the colonial government house, guardhouse, gunpowder magazine, and storehouses.

[14] As Anglo-American tensions rose again at the beginning of the 19th century, Major-General Isaac Brock ordered the construction of three artillery batteries, and a wall and dry moat on the western boundary of the fort.

[16] When news of the American declaration of war arrived at York, the regulars and military cavalry squad of the fort left for the Niagara peninsula, eventually participating in the Battle of Queenston Heights.

[19] After reports of approaching American ships reached the settlement, most professional troops in the area, First Nations-allied warriors, and some members of the local militia assembled at the fort.

[20] The regulars and militias stationed at the town's blockhouse were later ordered to reassemble at Fort York once it was made apparent that no landings would occur east of the settlement.

[13] In the following years, the forest around the fort was cleared to deprive Americans of cover in the event of another attack; and the defensive earthworks, barracks, and gunpowder magazine were rebuilt.

[29] The fort was not completed until around 1815; due to small numbers of artificer available at York, and a warm 1813–14 winter preventing the use of sleighs to transport supplies during that season.

[29] The fort operated as a hospital centre from the latter half of 1813 to the end of the war,[31] with the naval squadron stationed at York assisting in transporting wounded soldiers from the Niagara front to the town.

[33] However, the militia stationed in the fort shot at the vessel, resulting in the two sides exchanging fire before the Lady of the Lake withdrew back to its squadron outside the harbour.

[35] However, the fort's conditions was largely shaped by British foreign relations; as it suffered from poor maintenance during times of peace, and underwent repairs and reinforcing during perceived signs of hostilities.

[37] Although new fortifications were erected, the military continued to use Fort York's batteries to help defend the harbour;[38] and the adjacent open space for drills, and as a rifle range.

[39] In addition to its military uses, from 1839 to 1840, the old fort also hosted a Royal Society meteorological and magnetic observatory, before it was relocated to its permanent location at the University of King's College campus.

[13] The fort was eventually reinforced by the Queen's Rangers after the Battle of Montgomery's Tavern, with members of the militia descending on the city to defend the colonial government.

[35] During their two-year absence, the fort was largely maintained by a staff of 150 "enrolled pensioners," made up of British Army retirees who were granted land around the city following their retirement.

[42] Deteriorating Anglo-American relations in the 1860s as a result of the Trent Affair prompted the military to look into fortifying the Toronto garrison, using it as a base to repulse, or slow down, a potential invasion of Canada West.

[46] The last British imperial troops stationed at Fort York departed in 1871, alongside two Canadian militia regiments as a part of the Wolseley expedition.

[57] In 1994, the Friends of Fort York and Garrison Common was formed by local residents, with the organization later incorporated as a registered charity to support the national historic site.

Management of the Guard, which employed high school and university students clad in the uniforms of the Canadian Regiment of Fencible Infantry, was later assumed by the Friends of Fort York.

The Guard enlivened the site with musket, artillery, and music demonstrations in the summer months until 2022 when the municipal government suspended the grant used to support it, reportedly in the belief that living history displays perpetuated colonialism.

[58] In September 2017, Fort York served as the archery venue for the 2017 Invictus Games, a multi-parasports event for wounded, injured or sick armed forces personnel.

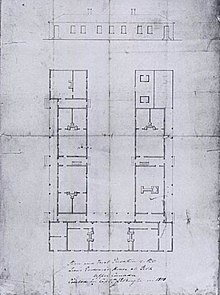

[13] The fort's buildings are surrounded by bastioned, stone-lined earthwork designed to absorb incoming cannon fire; with room for palisades to be placed on the earthen walls to prevent land assaults.

[74] However, due to the growth of the Railway Lands in the previous decade, the northern portion of the ramparts was rebuilt further south from its original location; with the wall's reconstruction also necessitating the demolition of a barracks.

The exterior southern facade of the building is made of monolithic weathering steel panels, reflecting where the historical escarpment and shoreline of the lake would be in the early 19th century.

[84] Certain parts of the southern facade feature a glass wall, with the steel panels placed in an "awning-like" position allowing visitors outside to glimpse into the museum.