Four Barbarians

"Four Barbarians" (Chinese: 四夷; pinyin: sìyí) was a term used by subjects of the Zhou and Han dynasties to refer to the four major people groups living outside the borders of Huaxia.

[a] Scholars such as Herrlee Glessner Creel[6] argue that Yi, Man, Rong, and Di were originally Chinese names of particular ethnic groups or tribes.

[b] The Russian anthropologist Mikhail Kryukov concludes: This would, in the final analysis, mean that once again territory had become the primary criterion of the we-group, whereas the consciousness of common origin remained secondary.

The sinologist Edwin G. Pulleyblank states that the name Yi "furnished the primary Chinese term for 'barbarian'," despite paradoxically being "considered the most civilized of the non-Chinese peoples.

Schuessler[10] defines Yi as "The name of non-Chinese tribes, prob[ably] Austroasiatic, to the east and southeast of the central plain (Shandong, Huái River basin), since the Spring and Autumn period also a general word for 'barbarian'", and proposes a "sea" etymology, "Since the ancient Yuè (=Viet) word for 'sea' is said to have been yí, the people's name might have originated as referring to people living by the sea".

[12] Ignoring this historical paleography, the Chinese historian K. C. Wu claimed that Yi should not be translated as "barbarian" because the modern graph implies a big person carrying a bow, someone to perhaps be feared or respected, but not to be despised.

[20] In Chinese Buddhism, siyi (四夷) or siyijie (四夷戒) abbreviates the si boluoyi (四波羅夷) "Four Parajikas" (grave offenses that entail expulsion of a monk or nun from the sangha).

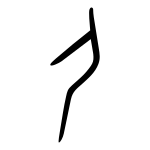

Bronze inscriptions and reliable documents from the Western Zhou period (c. 1046–771 BCE) used the word Yi in two meanings, says Chinese sinologist Chen.

Second, Yi meant specifically or collectively (e.g., zhuyi 諸夷) peoples in the remote lands east and south of China, such as the well-known Dongyi (東夷), Nanyi (南夷), and Huaiyi (淮夷).

Western Zhou bronzes also record the names of some little-known Yi groups, such as the Qiyi (杞夷), Zhouyi (舟夷), Ximenyi (西門夷), Qinyi (秦夷), and Jingyi (京夷).

[22] Inscriptions on bronze gui vessels (including the Xun 詢, Shiyou 師酉, and Shi Mi 史密) do not always use the term yi exclusively in reference to alien people of physically different ethnic groups outside China.

Shang people were employed in positions based upon their cultural legacy and education, such as zhu 祝 "priest", zong 宗 "ritual official", bu 卜 "diviner", shi 史 "scribe", and military commander.

The Chinese classics used it in directional compounds (e.g., "eastern" Dongyi 東夷, "western" Xiyi 西夷, "southern" Nanyi, and "northern" Beiyi 北夷), numerical (meaning "many") generalizations ("three" Sanyi 三夷, "four" Siyi 四夷, and "nine" Jiuyi 九夷), and groups in specific areas and states (Huaiyi 淮夷, Chuyi 楚夷, Qinyi 秦夷, and Wuyi 吳夷).

Therefore, even, though the soldiers went forth only once, their great accomplishments [victories] numbered twelve, and as a consequence none of the eastern Yi, western Rong, southern Man, northern Di, or the feudal lords of the central states failed to submit.

Dongyi occurs in a claim (4B/1)[43] that the legendary Chinese sages Shun and King Wen of Zhou were Yi: "Mencius said, 'Shun was an Eastern barbarian; he was born in Chu Feng, moved to Fu Hsia, and died in Ming T'iao.

If your deportment is respectful and reverent, your heart loyal and faithful, if you use only those methods sanctioned by ritual principles and moral duty, and if your emotional disposition is one of love and humanity, then though you travel throughout the empire, and though you find yourself reduced to living among the Four Yi 夷 tribes, everyone would consider you to be an honorable person.

The people of those [wufang 五方] five regions – the Middle states, and the Rong, Yi, (and other wild tribes round them) – had all their several natures, which they could not be made to alter.

The people of the Middle states, and of those Yi, Man, Rong, and Di, all had their dwellings, where they lived at ease; their flavours which they preferred; the clothes suitable for them; their proper implements for use; and their vessels which they prepared in abundance.

To make what was in their minds apprehended, and to communicate their likings and desires, (there were officers) – in the east, called transmitters; in the south, representationists; in the west, Di-dis; and in the north, interpreters.

Therefore, the sage-kings of antiquity paid particular attention to conforming to the endowment Heaven gave them in acting on their desires; all the people, therefore, could be commanded and all their accomplishments were firmly established.

The sword of the son of heaven has a point made of Swallow Gorge and Stone Wall … It is embraced by the four uncivilized tribes, encircled by the four seasons, and wrapped around by the Sea of Po.

(30)[54] Master Mo declared, "Long ago, when Yü was trying to stem the flood waters, he cut channels from the Yangtze and the Yellow rivers and opened communications with the four uncivilized tribes and the nine regions.

Yu understood that the world had become rebellious and thereupon knocked down the wall [built by his father Gun to protect Xia], filled in the moat surrounding the city, gave away their resources, burned their armor and weapons, and treated everyone with beneficence.

In the literary tradition, the four directions (north, south, east, west) are linked with four general categories of identification denoting a derogatory other (di, man, yi, rong).

The Dutch sinologist Kristofer Schipper cites a (c. 5th–6th century) Celestial Masters Daoist document (Xiaren Siyi shou yaolu 下人四夷受要籙) that substitutes Qiang 羌 for Man 蠻 in the Sìyí.

[67] The Liji records regional "interpreter" words for the Sìyí: ji 寄 for the Dongyi, xiang 象 for the Nanman, didi 狄鞮 for the Xirong, and yi 譯 for the Beidi.

The Ming Yongle Emperor established the Sìyí guǎn 四夷館 "Bureau of Translators" for foreign diplomatic documents in 1407, as part of the imperial Hanlin Academy.

(Article LI) states, "It is agreed, that henceforward the character "I" 夷 ('barbarian') shall not be applied to the Government or subjects of Her Britannic Majesty, in any Chinese official document."

This prohibition in the Treaty of Tientsin had been the end result of a long dispute between the Qing and British officials regarding the translation, usage and meaning of Yí.

Using the linguistic concept of heteroglossia, Lydia Liu analyzed the significance of yí in Articles 50 and 51 as a "super-sign": The law simply secures a three-way commensurability of the hetero-linguistic sign 夷/i/barbarian by joining the written Chinese character, the romanized pronunciation, and the English translation together into a coherent semantic unit.