Fourier-transform spectroscopy

The term "Fourier-transform spectroscopy" reflects the fact that in all these techniques, a Fourier transform is required to turn the raw data into the actual spectrum, and in many of the cases in optics involving interferometers, is based on the Wiener–Khinchin theorem.

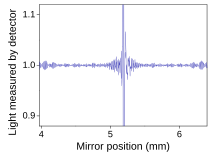

To be more specific, between the light source and the detector, there is a certain configuration of mirrors that allows some wavelengths to pass through but blocks others (due to wave interference).

The processing required turns out to be a common algorithm called the Fourier transform (hence the name, "Fourier-transform spectroscopy").

Because of the existing computer equipment requirements, and the ability of light to analyze very small amounts of substance, it is often beneficial to automate many aspects of the sample preparation.

In general, the goal of absorption spectroscopy is to measure how well a sample absorbs or transmits light at each different wavelength.

By making measurements of the signal at many discrete positions of the movable mirror, the spectrum can be reconstructed using a Fourier transform of the temporal coherence of the light.

In the most general description of pulsed FT spectrometry, a sample is exposed to an energizing event which causes a periodic response.

The frequency of the periodic response, as governed by the field conditions in the spectrometer, is indicative of the measured properties of the analyte.

Each spin exhibits a characteristic frequency of gyration (relative to the field strength) which reveals information about the analyte.

In Fourier-transform mass spectrometry, the energizing event is the injection of the charged sample into the strong electromagnetic field of a cyclotron.

Each traveling particle exhibits a characteristic cyclotron frequency-field ratio revealing the masses in the sample.

Pulsed FT spectrometry gives the advantage of requiring a single, time-dependent measurement which can easily deconvolute a set of similar but distinct signals.

Pulsed sources allow for the utilization of Fourier-transform spectroscopy principles in scanning near-field optical microscopy techniques.

[5] While the analysis of the interferometric output is similar to that of the typical scanning interferometer, significant differences apply, as shown in the published analyses.

The Fellgett advantage, also known as the multiplex principle, states that when obtaining a spectrum when measurement noise is dominated by detector noise (which is independent of the power of radiation incident on the detector), a multiplex spectrometer such as a Fourier-transform spectrometer will produce a relative improvement in signal-to-noise ratio, compared to an equivalent scanning monochromator, of the order of the square root of m, where m is the number of sample points comprising the spectrum.

However, if the detector is shot-noise dominated, the noise will be proportional to the square root of the power, thus for a broad boxcar spectrum (continuous broadband source), the noise is proportional to the square root of m, thus precisely offset the Fellgett's advantage.

Shot noise is the main reason Fourier-transform spectrometry was never popular for ultraviolet (UV) and visible spectra.