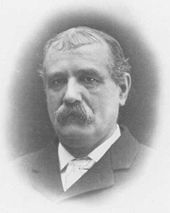

Francis Amasa Walker

Francis Amasa Walker (July 2, 1840 – January 5, 1897) was an American economist, statistician, journalist, educator, academic administrator, and an officer in the Union Army.

During his tenure, he placed the institution on more stable financial footing by aggressively fund-raising and securing grants from the Massachusetts government, implemented many curricular reforms, oversaw the launch of new academic programs, and expanded the size of the Boston campus, faculty, and student enrollments.

[10] As tensions between the North and South increased over the winter of 1860–1861, Walker equipped himself and began drilling with Major Devens' 3rd Battalion of Rifles in Worcester and New York.

Walker returned to Worcester but began to lobby William Schouler and Governor John Andrew to grant him a commission as a second lieutenant under Devens' command of the 15th Massachusetts.

[15] Following his 21st birthday and the First Battle of Bull Run in July 1861, Walker secured the consent of his father to join the war effort as well as assurances by Devens that he would receive an officer's commission.

Based upon his experiences in the military, Walker published two books describing the history of II Corps (1886) as well as a biography of General Winfield Scott Hancock (1884).

He also taught Latin, Greek, and mathematics at the Williston Seminary in Easthampton, Massachusetts until being offered an editorial position at the Springfield Republican by Samuel Bowles.

Cox, who had also previously served in McClellan's army and was currently the Secretary of the Interior under President Grant's administration, notified the twenty-nine-year-old Walker that he was being nominated to become the superintendent of the 1870 census.

Among the problems facing Walker included a lack of authority to determine, enforce, or control the marshals personnel, methods, or timing all of which were regularly manipulated by local political interests.

[43] Owing to the confluence of these problems, the Census was completed and tabulated several months behind schedule to much popular criticism, and led indirectly to a deterioration in Walker's health during the spring of 1871.

[47] The appointment was simultaneously a go-around to continue to fund Walker's federal responsibilities as Census superintendent despite Congress' cessation of appropriations for the position as well as a political opportunity to replace a scandal-ridden predecessor.

[54] Walker makes a number of moral arguments to support reparations for past actions toward Native Americans, including : “We may have no fear that the dying curse of the red man, outcast and homeless by our fault, will bring barrenness upon the soil that once was his, or dry the streams of the beautiful land that, through so much of evil and of good, has become our patrimony; but surely we shall be clearer in our lives, and freer to meet the glances of our sons and grandsons, if in our generation we do justice and show mercy to a race which has been impoverished that we might be made rich.”[55] He elevated the treatment of the natives to be one of the great issues of the time: “The United States will be judged at the bar of history according to what they shall have done in two respects, -by their disposition of negro slavery, and by their treatment of the Indians.”[56] 1876 was a busy year for Walker.

[67] Walker also used the position as a bully pulpit to advocate for the creation of a permanent Census Bureau to not only ensure that professional statisticians could be trained and retained but that the information could be better popularized and disseminated.

"[6] He said that without racial immigration restrictions, "every foul and stagnant pool of population in Europe, [in] which no breath of intellectual life has stirred for ages ... [will] be decanted upon our shores.

[6] As his Census obligations diminished in 1872, Walker reconsidered becoming an editorialist and even briefly entertained the idea of becoming a shoe manufacturer with his brother-in-law back in North Brookfield.

However, in October 1872, he was unanimously offered to fill Daniel Coit Gilman's vacated post at Yale's recently established Sheffield Scientific School led by the mineralogist George Jarvis Brush.

[83] Despite Walker's advocacy of profit sharing and expansion of educational opportunities using trade and industrial schools, he was an avowed opponent of the nascent socialist movement and published critiques of Edward Bellamy's popular novel Looking Backward.

[88] Walker's position on international bimetallism influenced his arguments that the primary cause of economic depressions was not land speculation, but rather constriction of the money supply.

Although he returned to the U.S. in October disheartened by the failure of the conference and exhausted by his obligations at the Exposition, the trip had secured Walker a commanding national and international reputation.

[92] Walker published International Bimetallism in 1896[93] roundly critiquing the demonetization of silver out of political pressure and the impact of this change on prices and profits as well as worker employment and wages.

[97] Robert Solow criticized the third edition (1888) for being devoid of facts, figures, and mostly full of off-the-cuff judgments on the practices and capacities of Native Americans and immigrants, but generally embodying the state of the art of economics at the time.

[100] Writing on immigrants from southern Italy, Hungary, Austria, and Russia in The Atlantic, Walker claimed, The entrance into our political, social, and industrial life of such vast masses of peasantry, degraded below our utmost conceptions, is a matter which no intelligent patriot can look upon without the gravest apprehension and alarm.

They have none of the ideas and aptitudes which fit men to take up readily and easily the problem of self-care and self-government, such as belong to those who are descended from the tribes that met under the oak-trees of old Germany to make laws and choose chieftains.

[104] Walker ultimately accepted in early May and was formally elected president by the MIT Corporation on May 25, 1881, resigning his Yale appointment in June and his Census directorship in November.

[110] In light of the difficulties in raising capital for these expansions and despite MIT's privately endowed status, Walker and other members of the Corporation lobbied the Massachusetts legislature for a $200,000 grant to aid in the industrial development of the Commonwealth ($4,974,000 in 2016 dollars).

[113] With the financial health of the Institute only beginning to recover, Walker began construction on the partially-funded expansion, fully expecting the immediacy of the project to be a persuasive tool for raising its funds.

[116] Walker also set out to reform and expand the institute's organization by creating a smaller Executive Committee, apart from the fifty-member Corporation, to handle regular administrative issues.

These reforms were largely a response to Walker's on-going defense of the Institute and its curriculum from outside accusations of overwork, poor writing, inapplicable skills, and status as a "mere" trade school.

The new Beaux-Arts campus opened in 1916, and featured a neo-classical Walker Memorial building housing a gymnasium, students' club and lounge, and a commons room.

The medal was awarded to Wesley Clair Mitchell in 1947, John Maurice Clark in 1952, Frank Knight in 1957, Jacob Viner in 1962, Alvin Hansen in 1967, Theodore Schultz in 1972, and Simon Kuznets in 1977.