Freeman on the land movement

[13] Canada developed its own tradition of pseudolaw and tax protesters, which merged over time with ideas from the American sovereign citizen movement.

[13] In 1945, Walter Frederick Kuhl MP delivered a speech in the House of Commons in which he argued, based on Smith's theories, that the Canadian constitution was defective and needed to be amended.

[13] Warman claimed that whereas in the United States, an individual's Social Security Number was used to attach this "strawman" to a natural person, in Canada, this was done using a birth certificate.

[16] Around 2000, Warman also worked with Ernst Friedrich Kyburz and Sikander Abdulali "Alex" Muljiani to promote anti-tax ideas based on the sovereign citizen movement's beliefs, at joint seminars across Canada.

As of 2016, the last "guru" actively teaching Detaxer theories was David Kevin Lindsay,[13] a serial litigant who participated in hundreds of court cases as a plaintiff or as an "agent" acting on behalf of others.

[16] A former construction worker and stand-up comic,[23] Menard entered pseudolaw as a student of Detaxer theories, which he later espoused on the Internet, using online forums such as "Cannabis culture", videos and freely distributed ebooks.

[16] Donald J. Netolitzky comments that despite Menard's stature in pseudolegal circles, his understanding of law is "best described as unsophisticated", and "grossly inferior" to that of Detaxer gurus such as David Kevin Lindsay.

[24] The notable difference between the Detaxer and freemen on the land populations is that the latter shows a politically leftist orientation, open to environmentalism, anti-globalization concepts and marijuana advocacy.

[16] Besides claiming that governments and statute laws are illegitimate and refusing to pay income tax, movement members reject the use of official documents such as health cards and driver's licences.

[29] In 2013, Canadian media reported the case of a Calgary woman whose tenant, a freeman on the land, had claimed her property as his own and declared it an "embassy".

[9][13] Unlike Menard who had begun his activities in far-left circles, Clifford had a white supremacist and skinhead background: his earlier adherents came largely from these environments.

[35] After his release, he endeavored to restore his status in the pseudolaw community[13] and operated for a time a company which purported to discharge customers' debts through an "A4V" scheme.

He stood out by using actual Canadian legal resources to develop pseudolegal concepts more sophisticated than Menard's,[16] as well as a new definition of the strawman theory based on misinterpretations of international texts.

[24] However, Spirit's attempt to develop a serious freeman on the land legal thinking proved a "two-edged sword"[16] when his concepts were refuted in Canadian provincial and Federal courts.

[12] The decline of Menard as a guru was also caused by the lack of success of his other initiatives such as the creation of the "peace officers" corps, of an alternative community and government structure, and a touring arts and crafts event.

[13] His reputation in the freeman on the land community was especially damaged by the failure of his AACP scheme, when the substantial numbers of Canadian freemen who had paid to subscribe to it never received their "Menard Cards" and other promised benefits.

[13] He eventually disavowed his original pseudolegal theories, went on to promote equity as superior to common law, and appeared to revert back to his earlier right-wing and racist associations.

Use of pseudolaw in the UK is difficult to evaluate, but there is clear evidence of an active community using concepts mostly derived from Canadian freeman on the land sources.

Unlike Canadian freemen who primarily use pseudolaw to justify illegal activity, UK litigants mostly focus on economic issues, such as avoiding Council Tax, motor vehicle registration and insurance, television licence fees, mortgages, and other debts.

[16] The expansion of pseudolegal "freeman" activity in Ireland was fostered by a period of economic difficulties in the late 2000s, following the burst of a real-estate bubble which led people to seek remedies for their financial woes.

[16] Canadian legal scholar Donald J. Netolitzky commented that the "freeman" population had an "amorphous" character and was "less an organization or 'movement' than a collection of individuals who hold powerful anti-authority beliefs".

OSTF Founder Mark McMurtrie, an Aboriginal Australian man, has produced YouTube videos speaking about "common law", which incorporate Freemen beliefs.

In 2018, The White Pendragons, a group of freemen on the land whose ideology combined pseudolaw with anti-government, anti-immigration and anti-Islam views, tried to "arrest" London Mayor Sadiq Khan.

[16] In Ireland, the Tir na Saor website, which operated from 2009 to 2016, was a major hub for the Irish pseudolaw community and showed clear Canadian freeman influences.

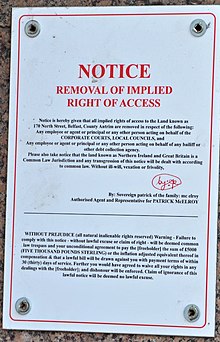

Menard created the original NOUICR template, which was later adapted and revised by many other freemen "gurus" to expand the rights claimed in the document or to make it appear more authoritative.

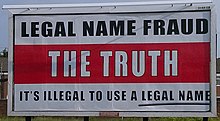

Freemen believe that the government is constantly trying to trick people into entering into a contract with them, so they often return bills, notices, summons and so on with the message "No contract—return to sender".

[10] This belief extends to Freemen's use of the "Notices of Understanding, Intent, and Claim of Right" which they consider stand as fact if any government actor can be persuaded to file them and does not rebut them afterwards.

[52] A common pseudolegal belief, originating in the redemption and sovereign citizen movements, is that people have two parts to their existence: their "flesh and blood" identity as individuals and their legal "person".

[20] [emphasis in original]In refuting each of the arguments used by Meads, Rooke concluded that "a decade of reported cases, many of which he refers to in his ruling, have failed to prove a single concept advanced by OPCA litigants".

[50] The whole process meant that a simple matter of driving without insurance took up hours of police time – and ultimately a stint behind bars after being convicted of contempt of court while defending himself.