Freeze-casting

The resulting green body contains anisotropic macropores in a replica of the sublimated ice crystals and structures from micropores to nacre-like packing[9] between the ceramic or metal particles in the walls.

The first observation of cellular structures resulting from the freezing of water goes back over a century,[12] but the first reported instance of freeze-casting, in the modern sense, was in 1954 when Maxwell et al.[13] attempted to fabricate turbosupercharger blades out of refractory powders.

[27] Assuming, however, that we are operating at speeds below vc and above those which produce a planar front, we will achieve some cellular structure with both ice-crystals and walls composed of packed ceramic particles.

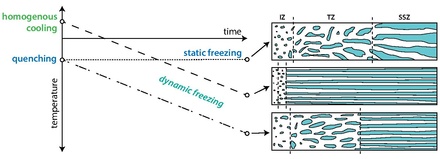

A competitive growth process develops between two crystal populations, those with their basal planes aligned with the thermal gradient (z-crystals) and those that are randomly oriented (r-crystals) giving rise to the start of the TZ.

Within the transition zone, the r-crystals either stop growing or turn into z-crystals that eventually become the predominant orientation, and lead to steady-state growth.

Thermodynamics dictate that all crystals will tend to align with the preferential temperature gradient causing r-crystals to eventually give way to z-crystals, which can be seen from the following radiographs taken within the TZ.

[2] The microstructure of a freeze-cast within the SSZ is defined by its wavelength (λ) which is the average thickness of a single ceramic wall plus its adjacent macropore.

[36] There are two general categories of tools for architecture a freeze-cast: Initially, the materials system is chosen based on what sort of final structure is needed.

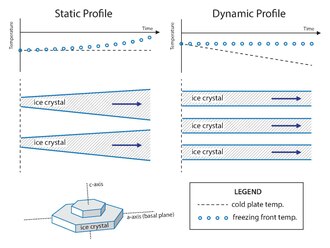

The microstructural wavelength (average pore + wall thickness) can be described as a function of the solidification velocity v (λ= Av−n) where A is dependent on solids loading.

[28][32] It has been shown that a linearly decreasing temperature on one side of a freeze-cast will result in near-constant solidification velocity, yielding ice crystals with an almost constant thickness along the SSZ of an entire sample.

In 2013, Deville et al.[45] made the observation that the periodicity of these dendrites (tip-to-tip distance) actually seems to be related to the primary crystal thickness.

At a certain point nearing the end of the transition zone, the particle-rich phase fraction rises sharply since z-crystals are less efficient at packing particles than r-crystals.

Using small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) they characterized the particle size, shape and interparticle spacing of nominally 32 nm silica suspensions that had been freeze-cast at different speeds.

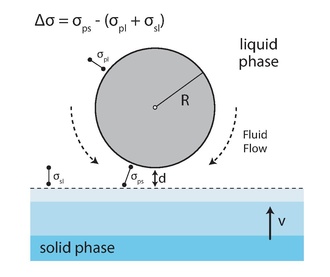

At low freezing rates, Brownian motion takes place, allowing particles to move easily away from the solid-liquid interface and maintain a homogeneous suspension.

[48] Most research into the mechanical properties of freeze casted structures focus on the compressive strength of the material and its yielding behavior at increasing stresses.

They found that the Young's modulus of the anisotropic structure was significantly higher than that of the isotropic aerogels, particularly when tested parallel to the freezing direction.

According to Ashby,[49] this deflection can be calculated from single beam theory, in which each of the cellular sections are idealized to be cubic shaped where each of the cell walls are assumed to be beam-like members with a square base.

[53] These models demonstrate that the bulk material selection can drastically impact the mechanical response of freeze casted structures under stress.

Other microstructural features such as the lamellar thickness, pore morphology and degree of macroporosity can also heavily influence the compressive strength and Young's modulus of these highly anisotropic structures.

[52] Freeze-casting can be applied to produce aligned porous structure from diverse building blocks including ceramics, polymers, biomacromolecules,[55] graphene and carbon nanotubes.

[56] Munch et al.[43] showed that it is possible to control the long-range arrangement and orientation of crystals normal to the growth direction by templating the nucleation surface.

In recent years, graphene[63] and carbon nanotubes[64] have been used to fabricate controlled porous structures using freeze casting methods, with materials often exhibiting outstanding properties.

Unlike aerogel materials produced without ice-templating, freeze cast structures of carbon nanomaterials have the advantage of possessing aligned pores, allowing, for example unparalleled combinations of low density and high conductivity.

The transport of fluids through aligned pores has led to the use of freeze casting as a method towards biomedical applications including bone scaffold materials.

The freeze casting of aligned porous fibres by spinning processes presents a promising method towards the fabrication of high performance insulating clothing articles.

In addition, materials with aligned pores produced via freeze casting from sintered nickel powder have gained significant attention in phase-change systems, such as loop heat pipes (LHPs), due to their excellent thermal properties.

This innovative approach eliminates interfacial resistance, ensuring seamless liquid transport while maintaining the high thermal conductivity and efficient capillary action required for optimal LHP performance.

These processes leverage the unique properties of porous metal structures, such as optimized reaction kinetics, enhanced thermal efficiency, and sustainability.

Similarly, in Steam Iron Process (SIP), dendritic pore structures ensure efficient water vapor distribution and maximize hydrogen yield.

The precise control over porosity and thermal properties afforded by freeze casting, along with the use of eco-friendly solvents like camphene, positions these foams as a vital innovation for scalable and sustainable hydrogen production, contributing to the fight against climate change.