Functional fixedness

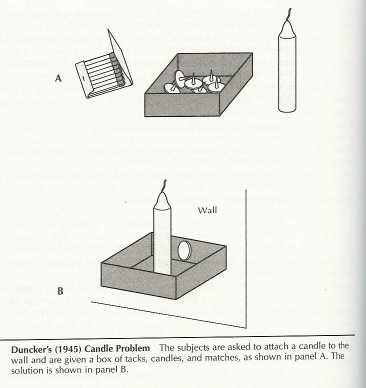

Karl Duncker defined functional fixedness as being a mental block against using an object in a new way that is required to solve a problem.

[2] Experimental paradigms typically involve solving problems in novel situations in which the subject has the use of a familiar object in an unfamiliar context.

In Duncker's terms, the participants were "fixated" on the box's normal function of holding thumbtacks and could not re-conceptualize it in a manner that allowed them to solve the problem.

For instance, participants presented with an empty tack box were two times more likely to solve the problem than those presented with the tack box used as a container[3] More recently, Frank and Ramscar (2003)[4] gave a written version of the candle problem to undergraduates at Stanford University.

The authors concluded that students' performance was contingent on their representation of the lexical concept "box" rather than instructional manipulations.

In its classic form, popularized by American test designer professor Alexander Calandra (1911–2006), the question asked the student to "show how it is possible to determine the height of a tall building with the aid of a barometer?

[7] Calandra's essay, "Angels on a Pin", was published in 1959 in Pride, a magazine of the American College Public Relations Association.

[12] The essay has been referenced frequently since,[13] making its way into books on subjects ranging from teaching,[14] writing skills,[15] workplace counseling,[16] and investment in real estate[17] to chemical industry,[18] computer programming,[19] and integrated circuit design.

[21] The study's purpose was to test if individuals from non-industrialized societies, specifically with low exposure to "high-tech" artifacts, demonstrated functional fixedness.

The study tested the Shuar, hunter-horticulturalists of the Amazon region of Ecuador, and compared them to a control group from an industrial culture.

The Shuar community had only been exposed to a limited amount of industrialized artifacts, such as machete, axes, cooking pots, nails, shotguns, and fishhooks, all considered "low-tech".

Two tasks were assessed to participants for the study: the box task, where participants had to build a tower to help a character from a fictional storyline to reach another character with a limited set of varied materials; the spoon task, where participants were also given a problem to solve based on a fictional story of a rabbit that had to cross a river (materials were used to represent settings) and they were given varied materials including a spoon.

The findings support the fact that students show positive transfer (performance) on problem solving after being presented with analogies of certain structure and format.

The experiment was a 2x2 design where conditions: "task contexts" (type and format) vs. "prior knowledge" (specific vs. general) were attested.

Inconclusive evidence was found for positive analogical transfer based on prior knowledge; however, groups did demonstrate variability.

The researcher suggested that a well-thought and planned analogy relevant in format and type to the problem-solving task to be completed can be helpful for students to overcome functional fixedness.

This study not only brought new knowledge about the human mind at work but also provides important tools for educational purposes and possible changes that teachers can apply as aids to lesson plans.

Latour performed an experiment researching this by having software engineers analyze a fairly standard bit of code—the quicksort algorithm—and use it to create a partitioning function.

[24] A comprehensive study exploring several classical functional fixedness experiments showed an overlying theme of overcoming prototypes.

Individuals are therefore thinking creatively and overcoming the prototypes that limit their ability to successfully complete the functional fixedness problem.

People trained in this technique solved 67% more problems that suffered from functional fixedness than a control group.