Functional genomics

The term functional genomics is often used to refer to the many technical approaches to study an organism's genes and proteins, including the "biochemical, cellular, and/or physiological properties of each and every gene product"[2] while some authors include the study of nongenic elements in their definition.

This could potentially provide a more complete picture of how the genome specifies function compared to studies of single genes.

The latter comprise a number of "-omics" such as transcriptomics (gene expression), proteomics (protein production), and metabolomics.

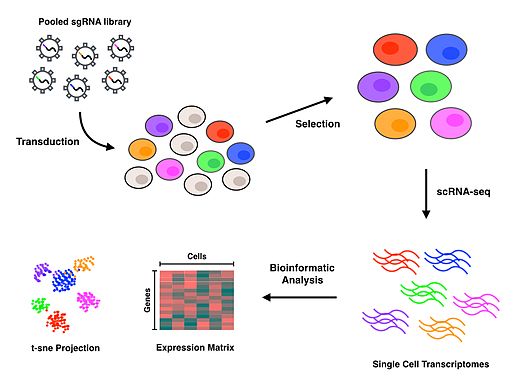

Functional genomics uses mostly multiplex techniques to measure the abundance of many or all gene products such as mRNAs or proteins within a biological sample.

Together these measurement modalities endeavor to quantitate the various biological processes and improve our understanding of gene and protein functions and interactions.

Microarrays measure the amount of mRNA in a sample that corresponds to a given gene or probe DNA sequence.

Probe sequences are immobilized on a solid surface and allowed to hybridize with fluorescently labeled "target" mRNA.

RNA sequencing has taken over microarray and SAGE technology in recent years, as noted in 2016, and has become the most efficient way to study transcription and gene expression.

Next-generation sequencing is the gold standard tool for non-coding RNA discovery, profiling and expression analysis.

Massively parallel reporter assays is a technology to test the cis-regulatory activity of DNA sequences.

One limitation of MPRAs is that the activity is assayed on a plasmid and may not capture all aspects of gene regulation observed in the genome.

STARR-seq is a technique similar to MPRAs to assay enhancer activity of randomly sheared genomic fragments.

In the original publication,[8] randomly sheared fragments of the Drosophila genome were placed downstream of a minimal promoter.

In vivo interaction of bait and prey proteins in a yeast cell brings the activation and binding domains of GAL4 close enough together to result in expression of a reporter gene.

While it is possible to assay every possible single amino-acid change due to combinatorics two or more concurrent mutations are hard to test.

This is critical to investigate the function of specific amino acids in a protein, e.g. in the active site of an enzyme.

Putative genes can be identified by scanning a genome for regions likely to encode proteins, based on characteristics such as long open reading frames, transcriptional initiation sequences, and polyadenylation sites.

The Rosetta stone approach is a computational method for de-novo protein function prediction.

Genomes are scanned for sequences that are independent in one organism and in a single open reading frame in another.

If two genes have fused, it is predicted that they have similar biological functions that make such co-regulation advantageous.

[24] This allows the user to infer if the selection process in nature applies similar constraints on a protein as the results of the deep mutational scan indicate.

[25] The authors used a thermodynamic model to predict the effects of mutations in different parts of a dimer.

[26][27] Results from MPRA experiments have required machine learning approaches to interpret the data.

Deep learning and random forest approaches have also been used to interpret the results of these high-dimensional experiments.

[29] These models are beginning to help develop a better understanding of non-coding DNA function towards gene-regulation.

[30] The genomic resource was developed to "enrich our understanding of how differences in our DNA sequence contribute to health and disease.