Game of Change

Employing a plan involving decoy players, the Bulldogs avoided being served an injunction as they took a charter plane to Michigan the day before the game.

[3] The following night, he violated the unwritten rule for the first time by starting Harkness, Rouse, Hunter, Miller, and Egan in the NIT consolation game.

[3] The spectators at the University of Houston, which would not fully desegregate until the next fall, shouted racial slurs, threw popcorn, ice, and pennies, and chanted, "Our team is red hot.

[7] In the late 1950s and early 1960s, head coach Babe McCarthy led the Mississippi State Bulldogs to much success in the Southeastern Conference (SEC).

[9]: 32 This became a greater point of contention as McCarthy's successes repeatedly earned NCAA tournament invitations, and the coach increasingly expressed his discontent at being held back from the national stage.

[2]: 193–94 As the civil rights movement was gaining traction around the country, the unwritten law began to face opposition from outside the team as well.

On February 25, 1963, the Bulldogs secured a tournament invitation with a win over Tulane, and that night, hundreds of students gathered outside the home of Dean W. Colvard, president of Mississippi State University since 1960, chanting "we want to go".

[10]: 836 Colvard had personally been in favor of attending the tournament in 1961 and 1962, but the question never came directly to him, and he felt he lacked the political capital to oppose figures such as Governor Ross Barnett on this issue so early in his presidency.

The previous year, Barnett had attempted to pressure the state board of higher education into denying the admission of James Meredith as the first black student at the University of Mississippi.

Many local newspapers ran columns that decried the decision as treasonous or as a threat to the state's unity; one anonymous letter wrote that "something more than the game will be lost".

[2]: 198–99 [11] Sending the team to the tournament was also favored by the players themselves, who unanimously indicated their desire to play when interviewed by The Clarion-Ledger,[9]: 92–93 [12] as well as by the general public, with a poll conducted by WJTV and WSLI reporting 85% approval.

[9]: 81 On March 5, the state board of higher education announced they would be holding a special session to review Colvard's decision.

The meeting was convened by trustee M. M. Roberts of Hattiesburg, whom Sports Illustrated's Alexander Wolff describes as a "tenacious lawyer and proud racist".

Billy Mitts and B. W. Lawson obtained an injunction from the Chancery Court of Hinds County forbidding the team from playing in the game.

Colvard and the university vice president fled to a motel in Birmingham, Alabama, and coach Babe McCarthy and the athletic director headed north to Nashville.

[10]: 847–48 On the morning of March 14, the day before the game was to be played, the team sent trainer Dutch Luchsinger and five reserve players to Starkville airport at 8 a.m. as decoys.

[9]: 99 The Clarion-Ledger reported that Deputy Sheriff Johnson went to the airport to serve the injunction, but left after learning that the plane had not yet arrived due to delays in Atlanta.

[2]: 213 Regardless of why, it is clear that the reserve squad did not encounter the deputy sheriff when they arrived, and thus returned to campus to reunite with the rest of the team.

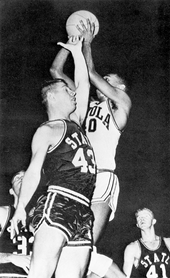

The underdog Mississippi State team started out with a jump shot and two lay-ups for a 7–0 lead, holding Loyola scoreless for several minutes.

The Bulldogs remained competitive in the game until forward Leland Mitchell, their leading scorer and rebounder, fouled out with 6:47 left.

[17][18][9]: 101–02 After the game, Loyola coach George Ireland praised Mississippi State as "the most deliberate offense we ran into all year".

An Art Heyman basket brought Duke within three points late in the second half, but Loyola rallied with a 10–0 scoring run and proceeded to a 94–75 victory.

[22][23] On July 10–11, 2013, members of the 1962–63 Loyola team reunited for a two-day trip to Washington, D.C. On the first day, they toured the Capitol Building and met privately with Senator Dick Durbin and House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi,[24] and on the second day, they met with President Barack Obama in the Oval Office.

[27] The 1962–63 Loyola Ramblers are often overlooked, or overshadowed by the 1965–66 Texas Western Miners, who won the 1966 NCAA championship with an all-black starting lineup over an all-white Kentucky team.

[28][29] The Miners' story gained prominence after the 2006 release of the film Glory Road, a dramatic retelling of the 1965–66 season and championship game.

[31] In a response letter to the editor, journalist Charles Paikert contends that, although the game did not cause sudden major change to ongoing racial tensions in the South, it did show that white athletes and students rejected the unwritten rule against interracial sports competitions.