History of the Puritans under King Charles I

He sent a strong delegation to the 1618–1619 Synod of Dort held in the Dutch Republic, and supported their condemnation of Arminianism as heretical, although he moderated his views when attempting to achieve a Spanish match for his son Charles, Prince of Wales.

While King Charles had no particular interest in theological questions, he preferred the emphasis of William Laud and the Caroline divines on order, decorum, uniformity, and High Church Anglicanism.

In 1625, shortly before the opening of the new parliament, Charles was married by proxy to Princess Henrietta Maria of France, the Catholic daughter of King Henri IV.

George Abbot, Archbishop of Canterbury from 1611, was in the mainstream of the English church, sympathetic with Scottish Protestants, anti-Catholic in a conventional Calvinist way, and theologically opposed to Arminianism.

When Parliament resumed in January 1629, Charles was met with outrage over the case of John Rolle, an MP who had been prosecuted for failing to pay Tonnage and Poundage.

The central ideal of Laudianism (the common name for the ecclesiastical policies pursued by Charles and Laud) was the "beauty of holiness" (a reference to Psalm 29:2).

In the late 1620s and early 1630s, Prynne had authored a number of works denouncing the spread of both Arminianism and Anglo-Catholicism in the Church of England, and was also opposed to King Charles' marriage to a Catholic princess.

At the same trial, Star Chamber also ordered that two other critics of the regime should have their ears cut off for writing against Laudianism: John Bastwick, a physician who wrote anti-episcopal pamphlets; and Henry Burton.

The authorities then resorted to flogging him with a three-thonged whip on his bare back, as he was dragged by his hands tied to the rear of an oxcart from Fleet Prison to the pillory at Westminster.

Nevertheless, in 1632, the Feoffees for Impropriations were dissolved and the group's assets forfeited to the crown: King Charles ordered that the money should be used to augment the salary of incumbents and used for other pious uses not controlled by the Puritans.

Charles intended to break the Treaty of Berwick at the next opportunity, and upon returning to London, began preparations for calling a Parliament that could pass new taxes to fund a war against the Scots and to re-establish episcopacy in Scotland.

At the same time, the Scots (who had many contacts among the English Puritans) learned that the king was intending to break the Treaty of Berwick and make a second attempt at invading Scotland.

When the Short Parliament was dissolved without having granted Charles the money he requested, the Covenanters determined that the time was ripe to launch a preemptive strike against English invasion.

The campaign to enforce the Et Cetera Oath met with firm Puritan resistance, organized in London by Cornelius Burges, Edmund Calamy the Elder, and John Goodwin.

The Petition also restated several of the Puritans' routine complaints: the Book of Sports, the placing of communion tables altar-wise, church beautification schemes, the imposing of oaths, the influence of Catholics and Arminians at court, and the abuse of excommunication by the bishops.

During this debate, Harbottle Grimston famously called Laud "the roote and ground of all our miseries and calamities...the sty of all pestilential filth that hath infected the State and Government."

Many moderate MPs, such as Lucius Cary, 2nd Viscount Falkland and Edward Hyde, were dismayed: although they believed that Charles and Laud had gone too far in the 1630s, they were not prepared to abolish episcopacy.

When the bishops attempted to take their seats in the House of Lords in late 1641, a pro-Puritan, anti-episcopal mob, probably organized by John Pym, prevented them from doing so.

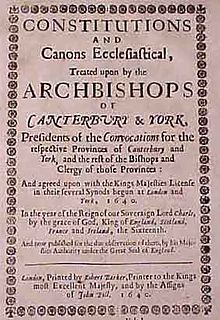

The Bishops Exclusion Act prevented those in holy orders from exercising any temporal jurisdiction or authority after 5 February 1642; this extended to taking a seat in Parliament or membership of the Privy Council.

In this period, Charles became increasingly convinced that a number of Puritan-influenced members of Parliament had treasonously encouraged the Scottish Covenanters to invade England in 1640, leading to the Second Bishops' War.

Following his failed attempt to arrest the Five Members, Charles realized that he was not only unpopular among parliamentarians, he was also in danger from London's pro-Puritan, anti-episcopal, and increasingly anti-royal mob.

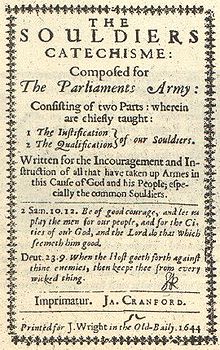

However, in summer 1643, shortly after the calling of the Westminster Assembly, the Parliamentary forces, under the leadership of John Pym and Henry Vane the Younger concluded an agreement with the Scots known as the Solemn League and Covenant.

However, in February 1644, five members of the Assembly – known to history as the Five Dissenting Brethren – published a pamphlet entitled "An Apologetical Narration, humbly submitted to the Honorable Houses of Parliament, by Thomas Goodwin, Philip Nye, Sidrach Simpson, Jeremiah Burroughs, & William Bridge."

The events of the 1640s caused the English legal community to worry that the Westminster Assembly was preparing to illegally alter the church in a way that overrode the Act of Supremacy.

Selden argued that not only English law, but the Bible itself required that the church be subordinate to the state: he cited the relationship of Zadok to King David and Romans 13 in support of this view.

In October 1645, the Scottish Commissioners succeeded when the Long Parliament voted in favour of an ordinance erecting a presbyterian form of church government in England.

The Westminster Assembly responded by sending a delegation, led by Stephen Marshall, a fiery preacher who had delivered several sermons to the Long Parliament, to protest the Erastian nature of the ordinance.

Parliament responded by sending a delegation which included Nathaniel Fiennes to the Westminster Assembly, along with a list of interrogatories related to the jure divino nature of church government.

Milton argued that the Long Parliament was imitating popish tyranny in the church; violating the biblical principle of Christian liberty; and engaging in a course of action that would punish godly men.

After the Purge, the remaining members (who were sympathetic to the Independent party and the Army Council)—henceforth known as the Rump Parliament—proceeded to do what the Long Parliament had refused to do: put Charles on trial for high treason.