Geʽez

Geʽez (/ˈɡiːɛz/[5] or /ɡiːˈɛz/;[6] ግዕዝ Gəʽ(ə)z[7] IPA: [ˈɡɨʕ(ɨ)z] ⓘ, and sometimes referred to in scholarly literature as Classical Ethiopic) is an ancient South Semitic language.

"[18] A similar problem is found for the consonant transliterated ḫ. Gragg notes that it corresponds in etymology to velar or uvular fricatives in other Semitic languages, but it is pronounced exactly the same as ḥ in the traditional pronunciation.

The reconstructed phonetic value of a phoneme is given in IPA transcription, followed by its representation in the Geʽez script and scholarly transliteration.

Geʽez ś ሠ Sawt (in Amharic, also called śe-nigūś, i.e. the se letter used for spelling the word nigūś "king") is reconstructed as descended from a Proto-Semitic voiceless lateral fricative [ɬ].

Like Arabic, Geʽez merged Proto-Semitic š and s in ሰ (also called se-isat: the se letter used for spelling the word isāt "fire").

Due to the high predictability of stress location in most words, textbooks, dictionaries and grammars generally do not mark it.

[16] Geʽez distinguishes two genders, masculine and feminine, the latter of which is sometimes marked with the suffix ት -t, e.g. እኅት ʼəxt ("sister").

In Geʽez, this is formed by suffixing the construct suffix -a to the possessed noun, which is followed by the possessor, as in the following examples:[35] ወልደwald-ason-constructንጉሥnəguśkingወልደ ንጉሥwald-a nəguśson-construct kingthe son of the kingስመsəm-aname-constructመልአክmalʼakangelስመ መልአክsəm-a malʼakname-construct angelthe name of the angelAnother common way of indicating possession by a noun phrase combines the pronominal suffix on a noun with the possessor preceded by the preposition /la=/ 'to, for':[36] ስሙsəm-uname-3SGለንጉሥla=nəguśto=kingስሙ ለንጉሥsəm-u la=nəguśname-3SG to=king'the king's name; the name of the king'Lambdin[37] notes that in comparison to the construct state, this kind of possession is only possible when the possessor is definite and specific.

show the question word at the beginning of the sentence: አየʾayy-awhich-ACCሀገረhagar-acity-ACCሐነጹḥanaṣ-ubuild-3PLአየ ሀገረ ሐነጹʾayy-a hagar-a ḥanaṣ-uwhich-ACC city-ACC build-3PLWhich city did they build?The common way of negation is the prefix ኢ ʾi- which descends from ʾəy- (which is attested in Axum inscriptions), from earlier *ʾay, from Proto-Semitic *ʾal by palatalization.

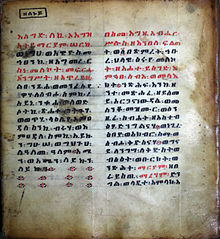

[39] It is prefixed to verbs as follows: ንሕነnəḥnaweኢንክልʾi-nəkl(we) cannotሐዊረḥawiragoንሕነ ኢንክል ሐዊረnəḥna ʾi-nəkl ḥawirawe {(we) cannot} gowe cannot goGeʽez is written with Ethiopic or the Geʽez abugida, a script that was originally developed specifically for this language.

The fourth stage began with the study of the Psalms of David and was considered an important landmark in a child's education, being celebrated by the parents with a feast to which the teacher, father confessor, relatives and neighbours were invited.

[40]However, works of history and chronography, ecclesiastical and civil law, philology, medicine, and letters were also written in Geʽez.

[44] Unlike previously assumed, the Geʽez language is now not regarded as an offshoot of Sabaean or any other forms of Old South Arabian.

[41][46] The oldest known example of the Geʽez script, unvocalized and containing religiously pagan references, is found on the Hawulti obelisk in Matara, Eritrea.

A number of these Books are called "deuterocanonical" (or "apocryphal" according to certain Western theologians), such as the Ascension of Isaiah, Jubilees, Enoch, the Paralipomena of Baruch, Noah, Ezra, Nehemiah, Maccabees, and Tobit.

Also to this early period dates Qerlos, a collection of Christological writings beginning with the treatise of Saint Cyril (known as Hamanot Reteʼet or De Recta Fide).

In the later 5th century, the Aksumite Collection—an extensive selection of liturgical, theological, synodical and historical materials—was translated into Geʽez from Greek, providing a fundamental set of instructions and laws for the developing Axumite Church.

Included in this collection is a translation of the Apostolic Tradition (attributed to Hippolytus of Rome, and lost in the original Greek) for which the Ethiopic version provides much the best surviving witness.

While there is ample evidence that it had been replaced by Amharic in the south and by Tigrinya and Tigre in the north, Geʽez remained in use as the official written language until the 19th century, its status comparable to that of Medieval Latin in Europe.

Apart from theological works, the earliest contemporary Royal Chronicles of Ethiopia are date to the reign of Amda Seyon I (1314–44).

Numerous homilies were written in this period, notably Retuʼa Haimanot ("True Orthodoxy") ascribed to John Chrysostom.

A letter of Abba ʼEnbaqom (or "Habakkuk") to Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi, entitled Anqasa Amin ("Gate of the Faith"), giving his reasons for abandoning Islam, although probably first written in Arabic and later rewritten in an expanded Geʽez version around 1532, is considered one of the classics of later Geʽez literature.

Around the year 1600, a number of works were translated from Arabic into Geʽez for the first time, including the Chronicle of John of Nikiu and the Universal History of George Elmacin.

[56][57][58][59] The first sentence of the Book of Enoch: ቃለQāla፡ በረከትbarakat፡ ዘሄኖክza-Henok፡ ዘከመzakama፡ ባረከbāraka፡ ኅሩያነḫəruyāna፡ ወጻድቃነwaṣādəqāna፡ እለʾəlla፡ ሀለዉhallawu፡ ይኩኑyəkunu፡ በዕለተbaʿəlata፡ ምንዳቤməndābe፡ ለአሰስሎlaʾasassəlo፡ ኵሉkʷəllu፡ እኩያንʾəkuyān፡ ወረሲዓንwarasiʿān። ቃለ ፡ በረከት ፡ ዘሄኖክ ፡ ዘከመ ፡ ባረከ ፡ ኅሩያነ ፡ ወጻድቃነ ፡ እለ ፡ ሀለዉ ፡ ይኩኑ ፡ በዕለተ ፡ ምንዳቤ ፡ ለአሰስሎ ፡ ኵሉ ፡ እኩያን ፡ ወረሲዓን ።Qāla {} barakat {} za-Henok {} zakama {} bāraka {} ḫəruyāna {} waṣādəqāna {} ʾəlla {} hallawu {} yəkunu {} baʿəlata {} məndābe {} laʾasassəlo {} kʷəllu {} ʾəkuyān {} warasiʿān {}"Word of blessing of Henok, wherewith he blessed the chosen and righteous who would be alive in the day of tribulation for the removal of all wrongdoers and backsliders."