Generalized Stokes theorem

Stokes' theorem was formulated in its modern form by Élie Cartan in 1945,[4] following earlier work on the generalization of the theorems of vector calculus by Vito Volterra, Édouard Goursat, and Henri Poincaré.

[5][6] This modern form of Stokes' theorem is a vast generalization of a classical result that Lord Kelvin communicated to George Stokes in a letter dated July 2, 1850.

[7][8][9] Stokes set the theorem as a question on the 1854 Smith's Prize exam, which led to the result bearing his name.

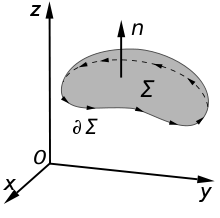

[9][10] This classical case relates the surface integral of the curl of a vector field

) in Euclidean three-space to the line integral of the vector field over the surface boundary.

), one can generalize the fundamental theorem of calculus, with a few additional caveats, to deal with the value of integrals (

is compactly supported in the domain of a single, oriented coordinate chart

This quantity is well-defined; that is, it does not depend on the choice of the coordinate charts, nor the partition of unity.

A (smooth) singular k-simplex in M is defined as a smooth map from the standard simplex in Rk to M. The group Ck(M, Z) of singular k-chains on M is defined to be the free abelian group on the set of singular k-simplices in M. These groups, together with the boundary map, ∂, define a chain complex.

the singular cohomology group Hk(M, Z)), defined using continuous rather than smooth simplices in M. On the other hand, the differential forms, with exterior derivative, d, as the connecting map, form a cochain complex, which defines the de Rham cohomology groups

Differential k-forms can be integrated over a k-simplex in a natural way, by pulling back to Rk.

Stokes' theorem says that this is a chain map from de Rham cohomology to singular cohomology with real coefficients; the exterior derivative, d, behaves like the dual of ∂ on forms.

On the level of forms, this means: De Rham's theorem shows that this homomorphism is in fact an isomorphism.

In other words, if {ci} are cycles generating the kth homology group, then for any corresponding real numbers, {ai} , there exist a closed form, ω, such that

To simplify these topological arguments, it is worthwhile to examine the underlying principle by considering an example for d = 2 dimensions.

The essential idea can be understood by the diagram on the left, which shows that, in an oriented tiling of a manifold, the interior paths are traversed in opposite directions; their contributions to the path integral thus cancel each other pairwise.

It thus suffices to prove Stokes' theorem for sufficiently fine tilings (or, equivalently, simplices), which usually is not difficult.

This classical statement is a special case of the general formulation after making an identification of vector field with a 1-form and its curl with a two form through

is not a smooth manifold with boundary, and so the statement of Stokes' theorem given above does not apply.

Whitney remarks that the boundary of a standard domain is the union of a set of zero Hausdorff

The study of measure-theoretic properties of rough sets leads to geometric measure theory.

Even more general versions of Stokes' theorem have been proved by Federer and by Harrison.

The traditional versions can be formulated using Cartesian coordinates without the machinery of differential geometry, and thus are more accessible.

The traditional forms are often considered more convenient by practicing scientists and engineers but the non-naturalness of the traditional formulation becomes apparent when using other coordinate systems, even familiar ones like spherical or cylindrical coordinates.

This special case is often just referred to as Stokes' theorem in many introductory university vector calculus courses and is used in physics and engineering.

in Euclidean three-space to the line integral of the vector field over its boundary.

Green's theorem is immediately recognizable as the third integrand of both sides in the integral in terms of P, Q, and R cited above.

Two of the four Maxwell equations involve curls of 3-D vector fields, and their differential and integral forms are related by the special 3-dimensional (vector calculus) case of Stokes' theorem.

If moving boundaries are included, interchange of integration and differentiation introduces terms related to boundary motion not included in the results below (see Differentiation under the integral sign): (with C and S not necessarily stationary) (with C and S not necessarily stationary) The above listed subset of Maxwell's equations are valid for electromagnetic fields expressed in SI units.

-form obtained by contracting the vector field with the Euclidean volume form.