Gene flow

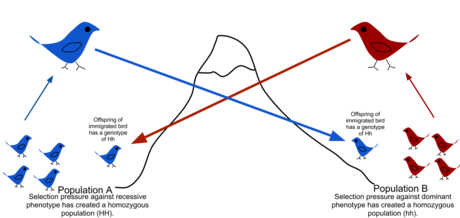

Migrants change the distribution of genetic diversity among populations, by modifying allele frequencies (the proportion of members carrying a particular variant of a gene).

Using the approximation based on the Island model, the effect of migration can be calculated for a population in terms of the degree of genetic differentiation(

However, when there is less than 1 migrant per generation (no migration), the inbreeding coefficient rises rapidly resulting in fixation and complete divergence (

[1] When gene flow is blocked by physical barriers, this results in Allopatric speciation or a geographical isolation that does not allow populations of the same species to exchange genetic material.

In some cases, they can be artificial, human-made barriers, such as the Great Wall of China, which has hindered the gene flow of native plant populations.

[14] One of these native plants, Ulmus pumila, demonstrated a lower prevalence of genetic differentiation than the plants Vitex negundo, Ziziphus jujuba, Heteropappus hispidus, and Prunus armeniaca whose habitat is located on the opposite side of the Great Wall of China where Ulmus pumila grows.

[14] [failed verification]This is because Ulmus pumila has wind-pollination as its primary means of propagation and the latter-plants carry out pollination through insects.

In human populations, genetic differentiation can also result from endogamy, due to differences in caste, ethnicity, customs and religion.

When a species exist in small populations there is an increased risk of inbreeding and greater susceptibility to loss of diversity due to drift.

[17] This was demonstrated in the lab with two bottleneck strains of Drosophila melanogaster, in which crosses between the two populations reversed the effects of inbreeding and led to greater chances of survival in not only one generation but two.

These processes can lead to homogenization or replacement of local genotypes as a result of either a numerical and/or fitness advantage of introduced plant or animal.

This is a direct result of evolutionary forces such as natural selection, as well as genetic drift, which lead to the increasing prevalence of advantageous traits and homogenization.

While some degree of gene flow occurs in the course of normal evolution, hybridization with or without introgression may threaten a rare species' existence.

The second is called the urban facilitation model, and suggests that in some populations, gene flow is enabled by anthropogenic changes to the landscape.

[23] Urban facilitation can occur in many different ways, but most of the mechanisms include bringing previously separated species into contact, either directly or indirectly.

The effectiveness of this depends on individual species’ dispersal abilities and adaptiveness to different environments to use anthropogenic structures to travel.

Human-driven climate change is another mechanism by which southern-dwelling animals might be forced northward towards cooler temperatures, where they could come into contact with other populations not previously in their range.

[24] This urban facilitation model was tested on a human health pest, the Western black widow spider (Latrodectus hesperus).

A study by Miles et al. collected genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphism variation data in urban and rural spider populations and found evidence for increased gene flow in urban Western black widow spiders compared to rural populations.

However, it is also an example of how urban facilitation, despite increasing gene flow, is not necessarily beneficial to an environment, as Western black widow spiders have highly toxic venom and therefore pose risks for human health.

The anthropogenic influence on bobcat migration pathways is an example of urban facilitation via opening up a corridor for gene flow.

This has implications for conservation: for example, urban facilitation benefits an endangered species of tarantula and could help increase the population size.

[25] Examples of this include the previously mentioned Western black widow spider, and also the cane toad, which was able to use roads by which to travel and overpopulate Australia.

[30] "Sequence comparisons suggest recent horizontal transfer of many genes among diverse species including across the boundaries of phylogenetic 'domains'.

"[31] Biologist Gogarten suggests "the original metaphor of a tree no longer fits the data from recent genome research".

Combining the simple coalescence model of cladogenesis with rare HGT events suggest there was no single last common ancestor that contained all of the genes ancestral to those shared among the three domains of life.

Differential hybridization also occurs because some traits and DNA are more readily exchanged than others, and this is a result of selective pressure or the absence thereof that allows for easier transaction.