Geology of the Canyonlands area

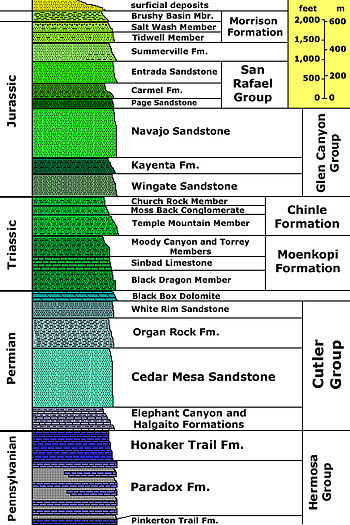

From the top of the mesa to the Honaker Trail Formation at the canyon river bottom, 150 million years of geologic stratum is exposed.

Various fossil-rich limestones, sandstones, and shales were deposited by advancing and retreating warm shallow seas through much of the remaining Paleozoic.

Vast deserts covered much of that part of North America, except for one period when streams for a time fought the sand dunes.

Great quantities of seawater were trapped in the subsiding basin and water became increasingly saline in the hot and dry climate.

Thousands of feet of evaporites (anhydrite and gypsum then halite) started to build up in the Mid Pennsylvanian and storms occasionally washed sediment from the nearby mountains.

Compressed salt beds from the Paradox started to flow plastically later in the Pennsylvanian and probably continued to move from then until the end of the Jurassic.

The Paradox is up to 5000 feet (1520 m) thick in places and in the park is exposed at the bottom of Cataract Canyon as rock gypsum inter-bedded with black shale.

Today these two competing rock units are exposed in a 4 to 5 mile (6.4 to 8 km) wide belt across the park, stretching from south of the Needles through the Maze and to the Elaterite Basin.

These sediments were deposited on flood plains by streams on an expansive lowland that was slightly sloped in the direction of an ocean to the west.

Triassic climates progressively became dryer, prompting the formation of sand dunes that buried dry stream beds and their flood plain.

Reddish-brown to lavender-colored sandstones interbedded with siltstones and shales constitute the resulting ledgy slope-forming Kayenta Formation.

A vast and very dry desert, not unlike the modern Sahara, covered 150,000 square miles (388,000 km2) of western North America.

Starting 70 million years ago and extending well into the Cenozoic, a mountain-building event called the Laramide orogeny uplifted the Rocky Mountains and with it the Canyonlands region.

Canyon widening and deepening was especially rapid for the gorges of the Green and Colorado Rivers, which were in part fed by glacier-melt from the Rocky Mountains.

These processes continue to shape the Canyonlands landscape in the Holocene (the current epoch), but at a slower rate due to a significant increase in aridity.