Geopolitics

Geopolitics (from Ancient Greek γῆ (gê) 'earth, land' and πολιτική (politikḗ) 'politics') is the study of the effects of Earth's geography on politics and international relations.

[5][6] According to Christopher Gogwilt and other researchers, the term is currently being used to describe a broad spectrum of concepts, in a general sense used as "a synonym for international political relations", but more specifically "to imply the global structure of such relations"; this usage builds on an "early-twentieth-century term for a pseudoscience of political geography" and other pseudoscientific theories of historical and geographic determinism.

Mahan's theoretical framework came from Antoine-Henri Jomini, and emphasized that strategic locations (such as choke points, canals, and coaling stations), as well as quantifiable levels of fighting power in a fleet, were conducive to control over the sea.

[13] Lea believed that while Japan moved against Far East and Russia against India, the Germans would strike at England, the center of the British Empire.

Both continued their influence on geopolitics after the end of the Cold War, writing books on the subject in the 1990s—Diplomacy and The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives.

Kissinger argued against the belief that with the dissolution of the USSR, hostile intentions had come to an end and traditional foreign policy considerations no longer applied.

"They would argue … that Russia, regardless of who governs it, sits astride the territory which Halford Mackinder called the geopolitical heartland, and it is the heir to one of the most potent imperial traditions."

Now, however, he focused on the beginning of the Cold War: "The objective of moral opposition to Communism had merged with the geopolitical task of containing Soviet expansion.

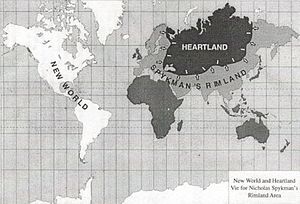

In classical Spykman terms, Brzezinski formulated his geostrategic "chessboard" doctrine of Eurasia, which aims to prevent the unification of this mega-continent.

"[14]The Austro-Hungarian historian Emil Reich (1854–1910) is considered to be the first having coined the term in English[22][7] as early as 1902 and later published in England in 1904 in his book Foundations of Modern Europe.

[24] Those scholars who look to MacKinder through critical lenses accept him as an organic strategist who tried to build a foreign policy vision for Britain with his Eurocentric analysis of historical geography.

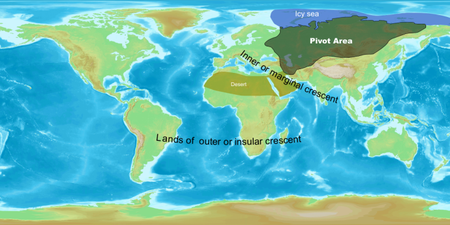

Mackinder's doctrine of geopolitics involved concepts diametrically opposed to the notion of Alfred Thayer Mahan about the significance of navies (he coined the term sea power) in world conflict.

The Heartland theory hypothesized a huge empire being brought into existence in the Heartland—which would not need to use coastal or transoceanic transport to remain coherent.

This theory can be traced in the origins of containment, a U.S. policy on preventing the spread of Soviet influence after World War II (see also Truman Doctrine).

[citation needed] The geopolitical theory of Ratzel has been criticized as being too sweeping, and his interpretation of human history and geography being too simple and mechanistic.

[31] After World War I, the thoughts of Rudolf Kjellén and Ratzel were picked up and extended by a number of German authors such as Karl Haushofer (1869–1946), Erich Obst, Hermann Lautensach, and Otto Maull.

[32] Nevertheless, German Geopolitik was discredited by its (mis)use in Nazi expansionist policy of World War II and has never achieved standing comparable to the pre-war period.

[citation needed] The resultant negative association, particularly in U.S. academic circles, between classical geopolitics and Nazi or imperialist ideology, is based on loose justifications.

Classical geopolitics forms an important element of analysis for military history as well as for sub-disciplines of political science such as international relations and security studies.

[34] In disciplines outside geography, geopolitics is not negatively viewed (as it often is among academic geographers such as Carolyn Gallaher or Klaus Dodds) as a tool of imperialism or associated with Nazism, but rather viewed as a valid and consistent manner of assessing major international geopolitical circumstances and events, not necessarily related to armed conflict or military operations.

However, in complete opposition to Ratzel's vision, Reclus considers geography not to be unchanging; it is supposed to evolve commensurately to the development of human society.

French geographer and geopolitician Jacques Ancel (1879–1936) is considered to be the first theoretician of geopolitics in France, and gave a notable series of lectures at the European Center of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Paris and published Géopolitique in 1936.

Braudel's broad view used insights from other social sciences, employed the concept of the longue durée, and downplayed the importance of specific events.

This method was inspired by the French geographer Paul Vidal de la Blache (who in turn was influenced by German thought, particularly that of Friedrich Ratzel whom he had met in Germany).

While rejecting the generalizations and broad abstractions employed by the German and Anglo-American traditions (and the new geographers), this school does focus on spatial dimension of geopolitics affairs on different levels of analysis.

Lacoste proposed that every conflict (both local or global) can be considered from a perspective grounded in three assumptions: Connected with this stream, and former member of Hérodote editorial board, the French geographer Michel Foucher developed a long term analysis of international borders.

[36] French philosopher Michel Foucault's dispositif introduced for the purpose of biopolitical research was also adopted in the field of geopolitical thought where it now plays a role.

[44] Various analysts state that China created the Belt and Road Initiative as a geostrategic effort to take a larger role in global affairs, and undermine what the Communist Party perceives as American hegemony.

Chen stated, "Regardless of the prospect, China through the BRI is deep in playing a 'New Great Game' in Central Asia that differs considerably from its historical precedent about 150 years ago when Britain and Russia jostled with each other on the Eurasian steppes.

"[52] In the Carnegie Endowment, Paul Stronski and Nicole Ng wrote in 2018 that China has not fundamentally challenged any Russian interests in Central Asia.