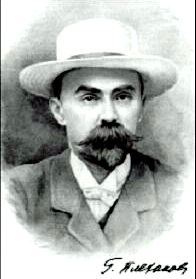

Georgi Plekhanov

Georgi Valentinovich Plekhanov was born 29 November 1856 (old style) in the Russian village of Gudalovka in the Tambov Governorate, one of twelve siblings.

[5] Georgi's mother, Maria Feodorovna, was a distant relative of the famous literary critic Vissarion Belinsky and was married to Valentin in 1855, following the death of his first wife.

[7] In 1871, Valentine Plekhanov gave up his effort to maintain his family as a small-scale landlord and accepted a job as an administrative official in a newly formed zemstvo.

[8] There in 1875 he was introduced to a young revolutionary intellectual named Pavel Axelrod, who later recalled that Plekhanov instantly made a favorable impression upon him:

[9]Under Axelrod's influence, Plekhanov was drawn into the populist movement as an activist in the primary revolutionary organization of the day, "Zemlia i Volia" (Land and Liberty).

On 6 December 1876, Plekhanov delivered a fiery speech during a demonstration in front of the Kazan Cathedral in Saint Petersburg in which he indicted the Tsarist autocracy and defended the ideas of Chernyshevsky.

When the question of terrorism became a matter of heated debate in the populist movement in 1879, Plekhanov cast his lot decisively with the opponents of political assassination.

[12] In the words of historian Leopold Haimson, Plekhanov "denounced terrorism as a rash and impetuous movement, which would drain the energy of the revolutionists and provoke a government repression so severe as to make any agitation among the masses impossible.

[12] Plekhanov founded a tiny populist splinter group called Chërnyi Peredel (Black Repartition), which attempted to wage a battle of ideas against the new organization of the growing terrorist movement, Narodnaya Volya (the People's Will).

[13] During the next three years, Plekhanov read extensively on political economy, gradually coming to question his faith in the revolutionary potential of the traditional village commune.

[16] In September 1883 Plekhanov joined with his old friend Pavel Axelrod, Lev Deutsch, Vasily Ignatov, and Vera Zasulich in establishing the first Russian-language Marxist political organization, the Gruppa Osvobozhdenie Truda or the "Emancipation of Labor Group."

[17] Based in Geneva, the Emancipation of Labor Group attempted to popularize the economic and historical ideas of Karl Marx, in which they met with some success, attracting such eminent intellectuals as Peter Struve, Vladimir Ulianov (Lenin), Iulii Martov, and Alexander Potresov to the organization.

[18] In 1900, Plekhanov, Pavel Axelrod, Zasulich, Lenin, Potresov, and Martov joined forces to establish a Marxist newspaper, Iskra (The Spark).

[18] The paper was intended to serve as a vehicle to unite various independent local Marxist groups into a single unified organization.

[18] From this effort emerged the Russian Social-Democratic Labor Party (RSDLP), an umbrella group which soon split into hostile Bolshevik and Menshevik political organizations.

[20] He believed the Bolsheviks were acting contrary to objective laws of history, which called for a stage of capitalist development before the establishment of socialist society would be possible in economically and socially backwards Russia and characterized the expansive goals of his radical opponents "political hallucinations.

The elected Zemstvos, which formed a local government in the European sectors of the Russian Empire, had been initiated by Nicholas' grandfather, Tsar Alexander II in 1864.

Later on 8 February 1895, Engels wrote directly to Plekhanov congratulating him on the "great success" of getting the book "published inside the country".

Plekhanov defended both Helvètius and Holbach from attacks by Friedrich Albert Lange, Jules–Auguste Soury and the other neo-Kantian idealist philosophers.

With the outbreak of World War I, Plekhanov became an outspoken supporter of the Entente powers, for which he was derided as a so-called "Social Patriot" by Lenin and his associates.

[40] He soon came to terms with the event, however, conceiving of it as a long-anticipated bourgeois-democratic revolution which would ultimately bolster flagging popular support for the war effort and he returned home to Russia.

[40] Plekhanov was extremely hostile to the Bolshevik Party headed by Lenin and was the top leader of the tiny Yedinstvo group, which published a newspaper by the same name.

[40] Plekhanov lent support to the idea that Lenin was a "German agent" and urged the Russian Provisional Government of Alexander Kerensky to take severe repressive measures against the Bolshevik organization to halt its political machinations.

She trained as a doctor in Saint Petersburg (medical courses for women were first opened in 1873) and joined the ranks of the Populists or Narodniks, spending the summer of 1877 in the village of Shirokoe in Samara Oblast where she sought (without very much success) to raise the political consciousness of the local peasantry.

[41] She went to the front during the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878) where she recorded witnessing medical personnel treated badly, the sick cared for inadequately and military authorities engaged in theft and corruption.