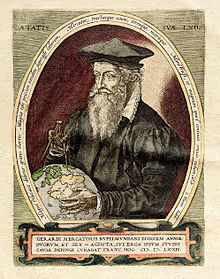

Gerardus Mercator

He is most renowned for creating the 1569 world map based on a new projection which represented sailing courses of constant bearing (rhumb lines) as straight lines—an innovation that is still employed in nautical charts.

His table of chronology ran to some 400 pages fixing the dates (from the time of creation) of earthly dynasties, major political and military events, volcanic eruptions, earthquakes and eclipses.

This period of persecution is probably the major factor in his move from Catholic Leuven (Louvain) to a more tolerant Duisburg, in the Holy Roman Empire, where he lived for the last thirty years of his life.

[e] Gerardus Mercator was born Geert or Gerard (De) Kremer (or Cremer) in Rupelmonde, Flanders, a small village to the southwest of Antwerp, which was in the fiefdom of Habsburg Netherlands.

The seventh child of Hubert (De) Kremer and his wife Emerance, his parents came from Gangelt in the Holy Roman Duchy of Jülich (present-day Germany).

The Brotherhood and the school was founded by the charismatic Geert Groote who placed great emphasis on study of the Bible and, at the same time, expressed disapproval of the dogmas of the church, both facets of the new "heresies" of Martin Luther propounded only a few years earlier in 1517.

During his time at the school the headmaster was Georgius Macropedius, and under his guidance Geert would study the Bible, the trivium (Latin, logic and rhetoric) and classics such as the philosophy of Aristotle, the natural history of Pliny and the geography of Ptolemy.

[m] Although the trivium was now augmented by the quadrivium[n] (arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, music), their coverage was neglected in comparison with theology and philosophy and consequently Mercator would have to resort to further study of the first three subjects in years to come.

[10] The arrival of Mercator on the cartographic scene would have been noted by the cognoscenti who purchased Gemma's globe – the professors, rich merchants, prelates, aristocrats and courtiers of the emperor Charles V at nearby Brussels.

His connection with this world of privilege was facilitated by his fellow student Antoine Perrenot, soon to be appointed Bishop of Arras, and Antoine's father, Nicholas Perrenot, the chancellor of Charles V. Working alongside Gemma whilst they were producing the globes, Mercator would have witnessed the process of progressing geography: obtaining previous maps, comparing and collating their content, studying geographical texts and seeking new information from correspondents, merchants, pilgrims, travellers and seamen.

[16] It was much favoured by humanist scholars who enjoyed its elegance and clarity as well as the rapid fluency that could be attained with practice, but it was not employed for formal purposes such as globes, maps and scientific instruments (which typically used Roman capitals or gothic script).

His visits to the free thinking Franciscans in Mechelen may have attracted the attention of the theologians at the university, amongst whom were two senior figures of the Inquisition, Jacobus Latomus and Ruard Tapper.

After seven months Mercator was released for lack of evidence against him but others on the list suffered torture and execution: two men were burnt at the stake, another was beheaded and two women were entombed alive.

In 1547 Mercator was visited by the young (nineteen year old) John Dee who, on completion of his undergraduate studies in Cambridge (1547), "went beyond the seas to speak and confer with some learned men".

[30] Celestial globes were a necessary adjunct to the intellectual life of rich patrons[y] and academics alike, for both astronomical and astrological studies, two subjects which were strongly entwined in the sixteenth century.

[37] Rumold, the third son, would spend a large part of his life in London's publishing houses providing for Mercator a vital link to the new discoveries of the Elizabethan age.

Accompanied by his son Bartholemew, Mercator meticulously triangulated his way around the forests, hills and steep sided valleys of Lorraine, difficult terrain as different from the Low Countries as anything could be.

He never committed anything to paper but he may have confided in his friend Ghim who would later write: "The journey through Lorraine gravely imperiled his life and so weakened him that he came very near to a serious breakdown and mental derangement as a result of his terrifying experiences.

The first element was the Chronologia,[44] a list of all significant events since the beginning of the world compiled from his literal reading of the Bible and no less than 123 other authors of genealogies and histories of every empire that had ever existed.

On the other hand, the Catholic Church placed the work on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum (List of Prohibited Books) because Mercator included the deeds of Martin Luther.

[48][46] As the Chronologia was going to press in 1569, Mercator also published what was to become his most famous map: Nova et Aucta Orbis Terrae Descriptio ad Usum Navigantium Emendate Accommodata ('A new and more complete representation of the terrestrial globe properly adapted for use in navigation').

[aj] The large size of what was a wall map meant that it did not find favour for use on board ship but, within a hundred years of its creation, the Mercator projection became the standard for marine charts throughout the world and continues to be so used to the present day.

[ak] Although several hundred copies of the map were produced[aa] it soon became out of date as new discoveries showed the extent of Mercator's inaccuracies (of poorly known lands) and speculations (for example, on the arctic and the southern continent).

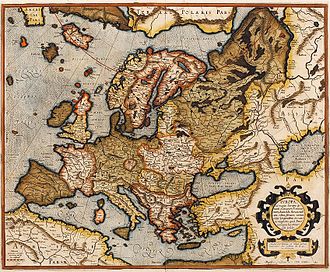

[al] Around this time the marshall of Jülich approached Mercator and asked him to prepare a set of European regional maps which would serve for a grand tour by his patron's son, the crown prince Johannes.

He compared the great many editions of the Ptolemy's written Geographia, which described his two projections and listed the latitude and longitude of some 8000 places, as well as the many different versions of the printed maps which had appeared over the previous one hundred years, all with errors and accretions.

In addition, the time he had available for cartography was reduced by a burst of writing on philosophy and theology: a substantial written work on the Harmonisation[ao] of the Gospels[54] as well as commentaries on the epistle of St. Paul and the book of Ezekiel.

[60] Of the titles identified there are 193 on theology (both Catholic and Lutheran), 217 on history and geography, 202 on mathematics (in its widest sense), 32 on medicine and over 100 simply classified (by Basson) as rare books.

The contents of the library provide an insight into Mercator's intellectual studies but the mathematics books are the only ones to have been subjected to scholarly analysis: they cover arithmetic, geometry, trigonometry, surveying, architecture, fortification, astronomy, astrology, time measurement, calendar calculation, scientific instruments, cartography and applications.

Hondius was an accomplished business man and under his guidance the Atlas was an enormous success; he (followed by his son Henricus, and son-in-law Johannes Janssonius) produced 29 editions between 1609 and 1641, including one in English.

[64] His construction of a chart on which the courses of constant bearing favoured by mariners appeared as straight lines ultimately revolutionised the art of navigation, making it simpler and therefore safer.