Germanic paganism

With a chronological range of at least one thousand years in an area covering Scandinavia, the British Isles, modern Germany, the Netherlands, and at times other parts of Europe, the beliefs and practices of Germanic paganism varied.

[4] In many contact areas (e.g. Rhineland and eastern and northern Scandinavia), Germanic paganism was similar to neighboring religions such as those of the Slavs, Celts, or Finnic peoples.

[28] The poems of the Edda, while pagan in origin, continued to circulate orally in a Christian context before being written down, which makes an application to pre-Christian times difficult.

[12] In contrast, pre-Christian images such as on bracteates, gold foil figures, and rune and picture stones are direct attestations of Germanic religion.

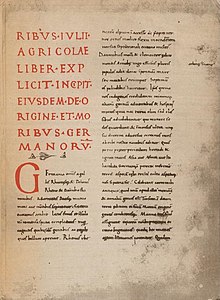

[35] Tacitus' reliability as a source can be characterized by his rhetorical tendencies, since one of the purposes of Germania was to present his Roman compatriots with an example of the virtues he believed they lacked.

[80][78] The Norse imagined the inhabited world to be surrounded by a sort of dragon or serpent, Jörmungandr; although only explicitly attested in Scandinavian sources, allusions to a world-surrounding monster from southern Germany and England suggest that this concept may have been common Germanic.

[81] Some Christian authors of the Middle Ages, such as Bede (c. 700) and Thietmar of Merseburg (c. 1000), attribute a strong belief in fate and chance to the followers of Germanic religion.

The number three often occurs as a symbol of completeness, which is probably how the frequent use in Germanic religion of triads of gods or giants should be understood.

[104] Groups of three gods are mentioned in a number of sources, including Adam of Bremen, the Nordendorf Fibula, the Old Saxon Baptismal Formula, Gylfaginning, and Þorsteins þáttr uxafóts.

[115] Words descended from Proto-Germanic *ansuz, the origin of the Old Norse family of gods known as the Aesir (singular Áss), are attested as a name for divine beings from around the Germanic world.

[120] There is no evidence for the existence of a separate Vanir family of gods outside of Icelandic mythological texts,[121] namely the Eddic poem Vǫluspá and Snorri Sturluson's Prose Edda and Ynglinga Saga.

[136] People's understanding of elves varied by time and place: in some instances they were godlike beings, in others dead ancestors, nature spirits, or demons.

[173] Collectives of three goddess known as matronae appear on numerous votive altars from the Roman province of Germania inferior, especially from Cologne,[174] dating to the third and fourth centuries CE.

[181] The disir share some functions with the Norns and valkyries,[182] and the Nordic sources suggest a close association between the three groups of Norse minor female deities.

[184] Besides Nerthus, Tacitus elsewhere mentions other important female deities worshiped by the Germanic peoples, such as Tamfana by the Marsi (Annals, 1:50) and the "mother of the gods" (mater deum) by the Aestii (Germania, chapter 45).

[189] She appears to have been associated with trade and commerce, and was possibly a chthonic deity: she is usually depicted with baskets of fruit, a dog, or the prow of a ship or an oar.

[197] Scholars generally believe that Tyr became less and less important in the Scandinavian branch of Germanic paganism over time and had largely ceased to be worshiped by the Viking Age.

[210] Odin (*Wodanaz) plays the main role in a number of myths as well as well-attested Norse rituals; he appears to have been venerated by many Germanic peoples in the early Middle Ages, though his exact characteristics probably varied in different times and places.

[234] He is sometimes known as Yngvi-Freyr, which would associate him with the god or hero *Ingwaz, the presumed progenitor of the Inguaeones found in Tacitus's Germania,[235] whose name is attested in the Old English rune poem (8th or 9th century CE) as Ing.

[239] The most important goddess in the recorded Old Norse pantheon was Freyr's sister, Freyja,[240] who features in more myths and appears to have been worshiped more than Frigg, Odin's wife.

[246] Julius Caesar and Tacitus claimed that the Germani did not venerate their gods in human form; however, this is a topos of ancient ethnography when describing supposedly primitive people.

[270] Tacitus mentions a temple of the goddess Tamfana in Annales 1.51, and also uses the word templum in reference to Nerthus in Germania, though this could simply mean a consecrated place rather than a building.

[306] Some scholars have discussed these images as related to shamanism, while others view animal art as similar to Skaldic kennings, capable of expressing both Christian and pagan meanings.

[312] While ritual specialists in Viking Age Scandinavia may have had defining insignia such as staffs and oath rings, it is unclear if they formed a hierarchy and they seem to have fulfilled non-cultic roles in society as well.

[318][319] Some insight into Germanic religion can be provided by burial customs,[321] which varied widely in time and space but nonetheless show a few consistent practices.

[91] Burials with dogs are found over a wide area through the migration period; it is possible that they were meant either to protect the deceased in the afterlife or to prevent the return of the dead as a revenant.

[353] The casting and drawing of lots to determine the future is well-attested among the Germanic peoples in medieval and ancient texts; linguistic analysis confirms that it was an old practice.

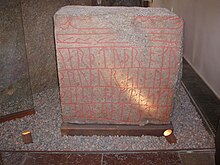

[379] Migration-age inscriptions on bracteates and later rune stones contain a number of early magical words and formulas, the best attested of which, alu, is found on multiple objects from 200 to 700 CE.

[407] Gregory of Tours, when describing a Frankish shrine near Cologne, depicts worshipers leaving wooden carvings of parts of the human body whenever they felt pain.

[424][425] A possible exception is the site of Alken Enge bog in Jutland: it contains the crushed and dismembered bodies of about 200 men, aged 13–45 years, who seem to have died on a battlefield.