Arginine:glycine amidinotransferase

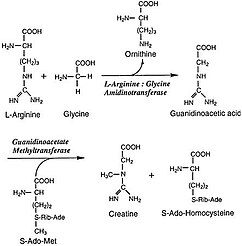

Creatine and its phosphorylated form play a central role in the energy metabolism of muscle and nerve tissues.

The second step of the process, producing the actual creatine molecule, occurs solely in the cytosol, where the second enzyme, S-adenosylmethionine:guanidinoacetate methyltransferase (GAMT), is found.

[1] The crystal structure of AGAT was determined by Humm, Fritsche, Steinbacher, and Huber of the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry in Martinsried, Germany in 1997.

The active site lies at the bottom of a long, narrow channel and includes a Cys-His-Asp catalytic triad.

[3] Consequently, the AGAT reaction is the most likely control step in the pathway, a hypothesis that is supported by a great deal of experimental work.

[4] It has been suggested that AGAT activity in tissues is regulated in a number of ways including induction by growth hormone and thyroxine,[5] inhibition of the enzyme by ornithine,[6] and repression of its synthesis by creatine.

In 2000, The American Journal of Human Genetics reported two female siblings, aged 4 and 6 years, with intellectual disability and severe creatine deficiency in the brain.

Because of its limited availability and high cost, the 1H-MRS technique cannot be proposed for all children whose clinical condition suggests the diagnosis of brain creatine depletion.

[11] Microarray analysis from one report shows a significant decrease in myocardial arginine:glycine amidinotransferase (AGAT) gene expression during the late-stage heart failure.