Glyptotherium

The genus was first described in 1903 by American paleontologist Henry Fairfield Osborn with the type species being, G. texanum, based on fossils that had been found in the Pliocene Blancan Beds in Llano Estacado, Texas, USA.

Another species, G. cylindricum, was named in 1912 by fossil hunter Barnum Brown on the basis of a partial skeleton that had been unearthed from the Pleistocene deposits in Jalisco, Mexico.

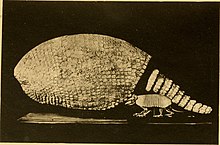

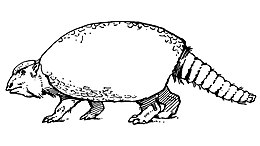

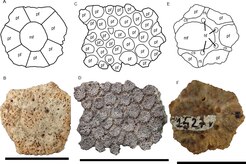

Glyptotherium was a large, quadrupedal (four-legged), herbivorous armadillo with an armored carapace (top shell) that was made of hundreds of interconnected osteoderms (structures in dermis composed of bone).

The armor could protect the animal from predators, of which many coexisted with Glyptotherium during its existence, including the "saber-tooth cat" Smilodon, the "bone-crushing dog" Borophagus, and the "short-faced bears" (Tremarctinae).

[2][3] The first Glyptotherium fossils to be described from the United States were described in 1888 by paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope and consisted only of a single carapace osteoderm that had been collected from the Lower Pleistocene "Equus Beds" of Nueces County, Texas.

[2][3] The next year, Joseph Leidy named Glyptodon floridanus based on isolated carapace osteoderms and pieces of caudal armor, though some were also referred to G. peltaliferus,[9] that were collected from Pleistocene deposits in DeSoto County, Florida.

[10][11] This species is now seen as a nomen vanum and considered a junior synonym of Glyptotherium cylindricum by a review of the genus by American paleontologists David Gillette and Clayton Ray (1981).

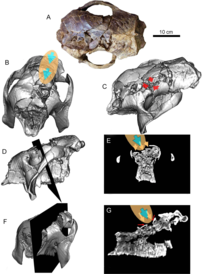

[2][16] Hay also described well preserved fossils, including skull elements and teeth, that were collected from Rancholabrean strata in Wolf City and Sinton, Texas that were referred to Cope's Glyptodon peltaliferus.

[22][24] One of the specimens reassigned to Glyptotherium, an isolated dorsal carapace osteoderm, was collected from Pleistocene age carbonate caves in Lagoa Santa, Minas Gerais, Brazil by Friedrich von Sellow during the early 1800s.

[22] In 2022, a host of fossils of Glyptotherium cylindricum including skulls, some preserving pathologies caused by humans, were described that had been collected from several sites in Falcón, northern Venezuela that dated to the Late Pleistocene.

[27] Glyptodontinae was classified in its own family or even superfamily until in 2016, when ancient DNA was extracted from the carapace of a 12,000 year old Doedicurus (a large, mace-clubbed glyptodont) specimen, and a nearly complete mitochondrial genome was reconstructed (76x coverage).

The following phylogenetic analysis was conducted by Frédéric Delsuc and colleagues in 2016 and represents the phylogeny of Cingulata using ancient DNA from Doedicurus to determine the position of it and other Glyptodonts:[27][29] Dasypodidae Euphractus Zaedyus Chaetophractus villosus Chaetophractus nationi C. vellerosus †Glyptodontinae (Doedicurus) Chlamyphorus Calyptophractus Priodontes Tolypeutes Cabassous The internal phylogeny of Glyptodontinae is convoluted and in a flux, with many species and families erected on the basis of fragmentary or undiagnostic material that lacks comprehensive review.

[18] Below is the phylogenetic analysis conducted by Cuadrelli et al., 2020 of Glyptodontinae, with Glyptodontidae as a family instead of subfamily, that focuses on advanced Glyptodonts:[33] Euphractus sexcinctus Pampatherium Boreostemma acostae Boreostemma venezolensis Glyptotherium cylindricum Glyptotherium texanum Glyptodon jatunkhirkhi Glyptodon reticulatus Glyptodon munizi Propalaehoplophorus australis Eucinepeltus petestatus Cochlops muricatus Plohophorus figuratus Pseudoplohophorus absolutus Eleutherocercus antiquus Doedicurus clavicaudatus Neosclerocalyptus ornatus Neosclerocalyptus paskoensis Hoplophorus euphractus Panochthus intermedius Panochthus tuberculatus Like its living relative, the armadillo, Glyptotherium had a shell that covered its entire torso, with smaller armor also covering the skull roof of the head, similar to a turtle.

[38] Glyptodont skulls have several unique features; the maxilla and palatine are enlarged vertically to make space for the molariforms, while the braincase is brachycephalic, short and flat.

[53] The genus was mainly a grazer but also had a mixed diet of C3 and C4 plants based on isotope analyses of dental specimens recovered from the Late Pleistocene Cedral locality in San Luis Potosí, México.

[60] Many extant species of armadillo have digging capabilities, with large claws adapted for scraping dirt to make burrows or forage for food underground.

[47][48] However, the evolution of a rigid carapace as opposed to a flexible one in extant armadillos as well as a weakly developed deltoid crest on the humerus (upper arm bone) provided evidence against fossorial hypotheses.

The Blancan age strata of western Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona preserves the gomphothere proboscideans Stegomastodon and Cuvieronius, equids represented by grazers like Nannipus and Equus.

In the Mexican state of Yucatan, fossils of Glyptotherium and the ground sloth Paramylodon are known from water-rich areas like riparian forests and swamps as opposed to open grasslands.

[76] In the Brazilian Intertropical Region (BIR) in eastern Brazil, Glyptotherium was a mixed grazer in arboreal savannahs, tropical grasslands, and other grassy areas near water sources.

Large, mesoherbivore mammals in the BIR were widespread and diverse, including the cow-like toxodontids Toxodon platensis and Piauhytherium, the macraucheniid litoptern Xenorhinotherium and equids such as Hippidion principale and Equus neogaeus.

Other xenarthran fossils are present in the area as well from several different families, like the giant megatheriid ground sloth Eremotherium, the scelidotheriids Catonyx and Valgipes, the mylodontids Glossotherium, Ocnotherium, and Mylodonopsis.

[80] This period of separation from the rest of the Earth's continents led to an age of unique mammalian evolution, with the dominance of groups such as marsupials, xenarthrans, and notoungulates in contrast to the North American mammal fauna.

Marsupials likely got to South America prior to its separation from the rest of Gondwana in the Late Cretaceous or Paleogene, although the origins of mammalian orders like Xenarthra and Notoungulata ended up on the continent remains a mystery.

[82][83] As for the fauna of North America, contemporary groups like canids, felids, ursids, tapirids, antilocaprids, and equids populated the region in addition to extinct families like gomphotheres, amphicyonids, and mammutids.

[88] The period following the Isthmus' foundation witnessed the extinction or extirpation of many groups, including the South American terror birds, toxodonts, macraucheniids, pampatheres, ground sloths, and glyptodonts.

[32] Subsequently, Glyptodon lived primarily in Andean and coastal sites, with Glyptotherium being known from grassland and lightly forested lowland deposits near aquatic areas, motivating its dispersal to the tropical regions of Venezuela and eastern Brazil.

[2][105] In the Blancan-Irvingtonian stages of the Early Pleistocene, G. texanum fossils are known from most of Mexico as well as the U.S. states of Arizona, Texas, Oklahoma, Florida, and possibly South Carolina.

[2][105] In the Rancholabrean of the Late Pleistocene, G. cylindricum evolved from G. texanum and its fossils have been unearthed from northern Venezuela, eastern Brazil, Central America, Mexico, and the U.S. states of Texas, Louisiana, Florida, and South Carolina.

[115] However, statistical analyses suggest that a later survival until the terminal Pleistocene of the United States is possible, based on sampling biases associated with uncommon fauna, and a lack of reliable dates from the humid Atlantic plain due to poor preservation.