Gravity turn

Second, and more importantly, during the initial ascent phase the vehicle can maintain low or even zero angle of attack.

A gravity turn is commonly used with rocket powered vehicles that launch vertically, like the Space Shuttle.

During this portion of the launch, gravity acts directly against the thrust of the rocket, lowering its vertical acceleration.

Losses associated with this slowing are known as gravity drag, and can be minimized by executing the next phase of the launch, the pitchover maneuver or roll program, as soon as possible.

The pitchover should also be carried out while the vertical velocity is small to avoid large aerodynamic loads on the vehicle during the maneuver.

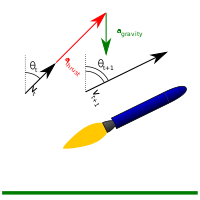

[1] The pitchover maneuver consists of the rocket gimbaling its engine slightly to direct some of its thrust to one side.

The pitchover angle varies with the launch vehicle and is included in the rocket's inertial guidance system.

This zeroing of the angle of attack reduces lateral aerodynamic loads and produces negligible lift force during the ascent.

If the rocket were not producing thrust, the flight path would be a simple ellipse like a thrown ball (it is a common mistake to think it is a parabola: this is only true if it is assumed that the Earth is flat, and gravity always points in the same direction, which is a good approximation for short distances), leveling off and then falling back to the ground.

Because heat shields and parachutes cannot be used to land on an airless body such as the Moon, a powered descent with a gravity turn is a good alternative.

[5] The vehicle begins by orienting for a retrograde burn to reduce its orbital velocity, lowering its point of periapsis to near the surface of the body to be landed on.

After the deorbit burn is complete the vehicle can either coast until it is nearer to its landing site or continue firing its engine while maintaining zero angle of attack.

After the coast and possible entry, the vehicle jettisons any no longer necessary heat shields and/or parachutes in preparation for the final landing burn.

In this case a gravity turn is not the optimal entry trajectory but it does allow for approximation of the true delta-v required.

If it is not already properly oriented, the vehicle lines up its engines to fire directly opposite its current surface velocity vector, which at this point is either parallel to the ground or only slightly vertical, as shown to the left.

This process is the mirror image of the pitch over maneuver used in the launch procedure and allows the vehicle to hover straight down, landing gently on the surface.

The pitch program maintains a zero angle of attack (the definition of a gravity turn) until the vacuum of space is reached, thus minimizing lateral aerodynamic loads on the vehicle.

Although the preprogrammed pitch schedule is adequate for some applications, an adaptive inertial guidance system that determines location, orientation and velocity with accelerometers and gyroscopes, is almost always employed on modern rockets.

[7] The initial pitch program is an open-loop system subject to errors from winds, thrust variations, etc.

To maintain zero angle of attack during atmospheric flight, these errors are not corrected until reaching space.

[8] Then a more sophisticated closed-loop guidance program can take over to correct trajectory deviations and attain the desired orbit.

To serve as an example of how the gravity turn can be used for a powered landing, an Apollo type lander on an airless body will be assumed.

After separation from the command module the lander performs a retrograde burn to lower its periapsis to just above the surface.

It has been shown that in this situation guidance can be achieved by maintaining a constant angle between the thrust vector and the line of sight to the orbiting command module.

Although gravity turn trajectories use minimal steering thrust they are not always the most efficient possible launch or landing procedure.

Several things can affect the gravity turn procedure making it less efficient or even impossible due to the design limitations of the launch vehicle.

In these cases it may be possible to perform a flyby of a nearby planet or moon, using its gravitational attraction to alter the ship's direction of flight.

Although in theory it is possible to execute a perfect free return trajectory, in practice small correction burns are often necessary during the flight.

The simplest case of the gravity turn trajectory is that which describes a point mass vehicle, in a uniform gravitational field, neglecting air resistance.