Great Purge

However, in the early 1930s, party officials began to lose faith in his leadership, largely due to the human cost of the first five-year plan and the collectivization of agriculture, notably including the Holodomor famine in Ukraine.

The threat of war heightened Stalin's and generally Soviet perception of marginal and politically suspect populations as the potential source of an uprising in case of invasion.

The political purge was primarily an effort by Stalin to eliminate challenge from past and potential opposition groups, including the left and right wings led by Leon Trotsky and Nikolai Bukharin, respectively.

Following the Civil War and reconstruction of the Soviet economy in the late 1920s, veteran Bolsheviks no longer thought necessary the "temporary" wartime dictatorship, which had passed from Lenin to Stalin.

As the purges began, the government (through the NKVD) shot Bolshevik heroes, including Mikhail Tukhachevsky and Béla Kun, as well as the majority of Lenin's Politburo, for disagreements in policy.

[35] From the October Revolution[37] onward,[38] Lenin had used repression against perceived and legitimate enemies of the Bolsheviks as a systematic method of instilling fear and facilitating control over the population in a campaign called the Red Terror.

These trials were highly publicized and extensively covered by the outside world, which was mesmerized by the spectacle of Lenin's closest associates confessing to most outrageous crimes and begging for death sentences:[original research?]

[27] Differently from Broué, one of his former allies,[55] Jules Humbert-Droz, said in his memoirs that Bukharin told him that he formed a secret bloc with Zinoviev and Kamenev in order to remove Stalin from leadership.

It was now alleged that Bukharin and others sought to assassinate Lenin and Stalin from 1918, murder Maxim Gorky by poison, partition the USSR and hand its territories to Germany, Japan, and Great Britain, and other charges.

[57] For some prominent communists such as Bertram Wolfe, Jay Lovestone, Arthur Koestler, and Heinrich Brandler, the Bukharin trial marked their final break with communism, and even turned the first three into fervent anti-communists eventually.

[60] Anastas Mikoyan and Vyacheslav Molotov later claimed that Bukharin was never tortured, but it is now known[neutrality is disputed] that his interrogators were given the order "beating permitted", and were under great pressure to extract confession out of the "star" defendant.

[61] Bukharin's confession in particular became subject of much debate among Western observers, inspiring Koestler's acclaimed novel Darkness at Noon and philosophical essay by Maurice Merleau-Ponty in Humanism and Terror.

He finished his last plea with the words:[63][T]he monstrousness of my crime is immeasurable especially in the new stage of struggle of the U.S.S.R. May this trial be the last severe lesson, and may the great might of the U.S.S.R. become clear to all.Romain Rolland and others wrote to Stalin seeking clemency for Bukharin, but all the leading defendants were executed except Rakovsky and two others (who were killed in NKVD prisoner massacres in 1941).

Despite the promise to spare his family, Bukharin's wife, Anna Larina, was sent to a labor camp, but she survived to see her husband posthumously rehabilitated a half-century later by the Soviet state under Mikhail Gorbachev in 1988.

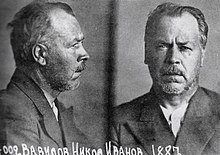

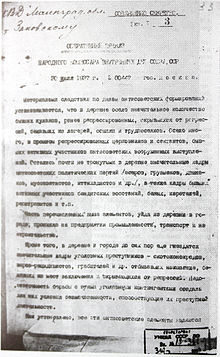

[citation needed] On 2 July 1937, in a top secret order to regional Party and NKVD chiefs Stalin instructed them to produce the estimated number of "kulaks" and "criminals" in their districts.

The following categories appear to have been on index-cards, catalogues of suspects assembled over the years by the NKVD and were systematically tracked down: "ex-kulaks" previously deported to "special settlements" in inhospitable parts of the country (Siberia, the Urals, Kazakhstan, and the Far North), former tsarist civil servants, former officers of the White Army, participants in peasant rebellions, members of the clergy, persons deprived of voting rights, former members of non-Bolshevik parties, ordinary criminals, like thieves, known to the police and various other "socially harmful elements".

[25] Local units of the NKVD, in order to meet their "casework minimums" and force confessions out of arrestees worked long uninterrupted shifts during which they interrogated, tortured and beat the prisoners.

[73] Timothy Snyder attributes 300,000 deaths during the Great Purge to "national terror" including ethnic minorities and Ukrainian "kulaks" who had survived dekulakization and the Holodomor famine that had been used to kill millions in the early 1930s.

[89] Russian Trotskyist historian Vadim Rogovin argued that Stalin had destroyed thousands of foreign communists capable of leading socialist change in their respective countries.

[citation needed] A series of documents discovered in the Central Committee archives in 1992 by Vladimir Bukovsky demonstrate that there were limits for arrests and executions as for all other activities in the planned economy.

[163] Not only did foreign correspondents from the West fail to report on the purges, but in many Western nations (especially France), attempts were made to silence or discredit these witnesses;[164] according to Robert Conquest, Jean-Paul Sartre took the position that evidence of the camps should be ignored so the French proletariat would not be discouraged.

[165] According to Robert Conquest in his 1968 book The Great Terror: Stalin's Purge of the Thirties, with respect to the trials of former leaders, some Western observers were unintentionally or intentionally ignorant of the fraudulent nature of the charges and evidence, notably Walter Duranty of The New York Times, a Russian speaker; the American Ambassador, Joseph E. Davies, who reported, "proof ... beyond reasonable doubt to justify the verdict of treason";[166] and Beatrice and Sidney Webb, authors of Soviet Communism: A New Civilization.

He called them in 1941 "the great purges", and described how over four years they affected "the top fourth or fifth, to estimate it conservatively, of the Party itself, of the Army, Navy, and Air Force leaders and then of the new Bolshevik intelligentsia, the foremost technicians, managers, supervisors, scientists".

The first of these sources were the revelations of Nikita Khrushchev, which particularly affected the American editors of the Communist Party USA newspaper, the Daily Worker, who, following the lead of The New York Times, published the Secret Speech in full.

In his secret speech to the 20th CPSU congress in February 1956 (which was made public a month later), Khrushchev referred to the purges as an "abuse of power" by Stalin which resulted in enormous harm to the country.

Khrushchev later claimed in his memoirs that he had initiated the process, overcoming objections and protests from the rest of Party leadership, but the transcripts belie this, although they show differences of opinion regarding the contents.

"[189] In the late 1980s, with the formation of the Memorial Society and similar organisations across the Soviet Union at a time of Gorbachev's glasnost ("openness and transparency") it became possible not only to speak about the Great Terror but to begin locating the killing grounds of 1937–1938 and identifying those who lay buried there.

Robert Conquest emphasized Stalin's paranoia, focused on the Moscow show trial of "Old Bolsheviks", and analyzed the carefully planned and systematic destruction of the Communist Party.

[25] According to an October 1993 study published in The American Historical Review, much of the Great Purge was directed against the widespread banditry and criminal activity which was occurring in the Soviet Union at the time.

"[204]According to Nikita Khrushchev's 1956 speech, "On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences", and to historian Robert Conquest, a great number of accusations, notably those presented at the Moscow show trials, were based on forced confessions, often obtained through torture,[205] and on loose interpretations of Article 58 of the RSFSR Penal Code, which dealt with counter-revolutionary crimes.

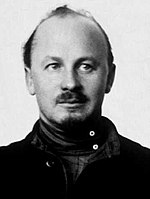

Red Army Air Forces , fell victim to the " Latvian Operation " in 1938