Italian irredentism

During World War I the main "irredent lands" (terre irredente) were considered to be the provinces of Trento and Trieste and, in a narrow sense, irredentists referred to the Italian patriots living in these two areas.

The liberation of Italia irredenta was perhaps the strongest motive for Italy's entry into World War I and the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 satisfied many irredentist claims.

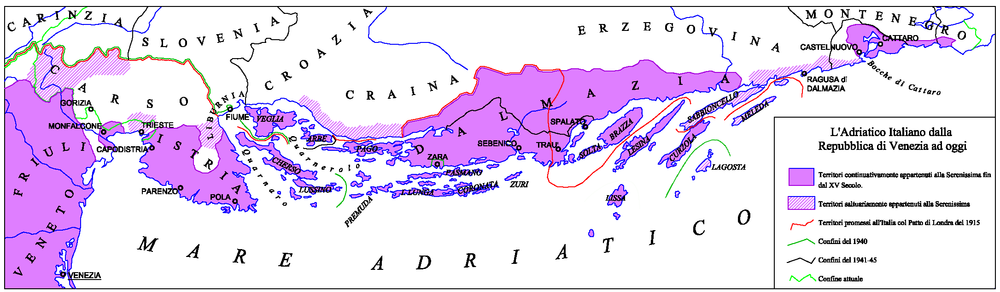

The areas targeted were Corsica, Dalmatia, Gorizia, Istria, Malta, County of Nice, Ticino, small parts of Grisons and of Valais, Trentino, Trieste and Fiume.

[9] Initially, the movement can be described as part of the more general nation-building process in Europe in the 19th and 20th centuries when the multi-national Austro-Hungarian, Russian and Ottoman Empires were being replaced by nation-states.

In Eastern Europe, where the Habsburg Empire had long asserted control over a variety of ethnic and cultural groups, nationalism appeared in a standard format.

[10] In the early 19th century the ideals of unification in a single Nation of all the territories populated by Italian-speaking people created the Italian irredentism.

The Kingdom of Sardinia again attacked the Austrian Empire in the Second Italian War of Independence of 1859, with the aid of France, resulting in the liberation of Lombardy.

[16] Giuseppe Garibaldi was elected in 1871 in Nice at the National Assembly where he tried to promote the annexation of his hometown to the newborn Italian unitary state, but he was prevented from speaking.

[17] Because of this denial, between 1871 and 1872 there were riots in Nice, promoted by the Garibaldini and called "Niçard Vespers",[18] which demanded the annexation of the city and its area to Italy.

Indeed, the final vote count on the referendum announced by the Court of Appeals was 130,839 in favour of annexation to France, 235 opposed and 71 void, showing questionable complete support for French nationalism (that motivated criticisms about rigged results).

On 16 March 1860, the provinces of Northern Savoy (Chablais, Faucigny and Genevois) sent to Victor Emmanuel II, to Napoleon III, and to the Swiss Federal Council a declaration - sent under the presentation of a manifesto together with petitions - where they were saying that they did not wish to become French and shown their preference to remain united to the Kingdom of Sardinia (or be annexed to Switzerland in the case a separation with Sardinia was unavoidable).

[11] However, after the Third Italian War of Independence (1866), when the Veneto and Friuli regions were ceded by the Austrians to the newly formed Kingdom of Italy, Istria and Dalmatia remained part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, together with other Italian-speaking areas on the eastern Adriatic.

[24] During the meeting of the Council of Ministers of 12 November 1866, Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria outlined a wide-ranging project aimed at the Germanization or Slavization of the areas of the empire with an Italian presence:[25] His Majesty expressed the precise order that action be taken decisively against the influence of the Italian elements still present in some regions of the Crown and, appropriately occupying the posts of public, judicial, masters employees as well as with the influence of the press, work in South Tyrol, Dalmatia and Littoral for the Germanization and Slavization of these territories according to the circumstances, with energy and without any regard.

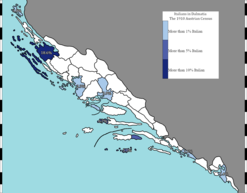

[31] Bartoli's evaluation was followed by other claims that Auguste de Marmont, the French Governor General of the Napoleonic Illyrian Provinces commissioned a census in 1809 which found that Dalmatian Italians comprised 29% of the total population of Dalmatia.

One consequence of irredentist ideas outside of Italy was an assassination plot organized against the Emperor Francis Joseph in Trieste in 1882, which was detected and foiled.

When the irredentist movement became troublesome to Italy through the activity of Republicans and Socialists, it was subject to effective police control by Agostino Depretis.

[40][41] Italy signed the Treaty of London (1915) and entered World War I with the intention of gaining those territories perceived by irredentists as being Italian under foreign rule.

In April 1918, in what he described as an open letter "to the American Nation" Paolo Thaon di Revel, Commander in Chief of the Italian navy, appealed to the people of the United States to support Italian territorial claims over Trento, Trieste, Istria, Dalmatia and the Adriatic, writing that "we are fighting to expel an intruder from our home".

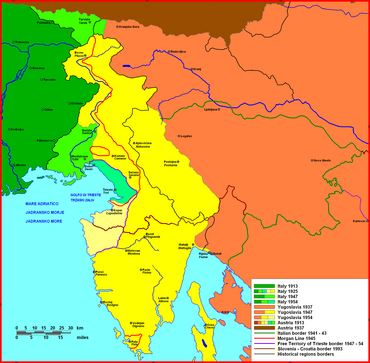

[43] The outcome of the World War I and the consequent settlement of the Treaty of Saint-Germain met some Italian claims, including many (but not all) of the aims of the Italia irredenta party.

In Dalmatia, despite the London Pact, only territories with Italian majority as Zara with some Dalmatian islands, such as Cherso, Lussino and Lagosta were annexed by Italy because Woodrow Wilson, supporting Yugoslav claims and not recognizing the treaty, rejected Italian requests on other Dalmatian territories, so this outcome was denounced as a "Mutilated victory".

The rhetoric of "Mutilated victory" was adopted by Benito Mussolini and led to the rise of Italian fascism, becoming a key point in the propaganda of Fascist Italy.

Historians regard "Mutilated victory" as a "political myth", used by fascists to fuel Italian imperialism and obscure the successes of liberal Italy in the aftermath of World War I.

Malta was heavily bombed, but was not occupied due to Erwin Rommel's request to divert to North Africa the forces that had been prepared for the invasion of the island.

Italy surrendered in September 1943 and over the following year, specifically between 2 November 1943 and 31 October 1944, Allied Forces bombarded the town fifty-four times.

Today, Italy, France, Malta, Greece, Croatia and Slovenia are all members of the European Union, while Montenegro and Albania are candidates for accession.

The 1947 Constitution of Italy established five autonomous regions (Sardinia, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Sicily, Aosta Valley and Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol), in recognition of their cultural and linguistic distinctiveness.

In the early 1990s, the breakup of Yugoslavia caused nationalistic sentiments to re-emerge in these areas; worthy of note in this regard are the demonstrations in Trieste on 6 October 1991 "for a new Italian irredentism".

These were promoted by the Italian Social Movement and inspired by rumours about negotiations for the passage through Trieste of the Yugoslav troops expelled from Slovenia during the Ten-Day War which saw the participation of thousands of people at the political rally in Piazza della Borsa followed by a long procession through the streets of the city, and on 8 November 1992, again in Trieste.

[64] The same Italian Social Movement and National Alliance asked for the review of the peace treaties signed by Italy after World War II, especially with regard to Zone B of the former Free Territory of Trieste, given that the qualification of Slovenia and Croatia as heirs of Yugoslavia was not a given and that the division of Istria between Slovenia and Croatia contradicted the clauses of the peace treaties which guaranteed the unity of the surviving Italian component in Istria (Istrian Italians), assigned to Yugoslavia after World War II, proposing the creation of an Istrian Euro-region also including the city of Rijeka.

[65] These claims, which also concerned Dalmatia (including islands such as Pag, Ugljan, Vis, Lastovo, Hvar, Korčula and Mljet) and the coast with the cities of Zadar, Šibenik, Trogir and Split, remained completely unheeded by all the Italian governments that followed one another in that period.