Greece runestones

[9] The older version of the Westrogothic law, which was written down by Eskil Magnusson, the lawspeaker of Västergötland 1219–1225, stated that "no man may receive an inheritance (in Sweden) while he dwells in Greece".

[20] However, as noted by Jansson (1987), the fact that most of these runestones were raised in Uppland and Södermanland does not necessarily mean that their number reflects the composition of the Scandinavians in the Varangian Guard.

A view held by scholars such as Erik Moltke and Sven B. F. Jansson holds that the runestones were primarily the result of the many Viking expeditions from Scandinavia,[22] or to cite Jansson (1987): When the great expeditions were over, the old trade routes closed, and the Viking ships no longer made ready each spring for voyages to east and west, then that meant the end of the carving and setting up of rune stones in the proper sense of the term.

[23] Sawyer (2000), on the other hand, reacts against this commonly held view and comments that the vast majority of the runestones were raised in memory of people who are not reported to have died abroad.

There is a long-standing practice of writing transliterations of the runes in Latin characters in boldface and transcribing the text into a normalized form of the language with italic type.

[28] The linguistic significance of the inscriptions lies in the use of the haglaz (ᚼ) rune to denote the velar approximant /ɣ/ (as in Ragnvaldr), something that would become common after the close of the Viking Age.

[45] Considering Ragnvald's background, it is not surprising that he rose to become an officer of the Varangian Guard: he was a wealthy chieftain who brought many ambitious soldiers to Greece.

[46] * rahnualtrRagnvaldr* litlet* ristarista* runarrunaʀ* efʀæftiʀ* fastuiFastvi,* moþurmoður* sinasina,* onemsOnæms* totʀdottiʀ,* todoii* aiþiÆiði.* kuþGuðhialbihialpi* antand* henahænnaʀ.

litu ' rita : stain þino * iftiʀ * o-hu... ...an hon fil o kriklontr kuþ hi-lbi sal...]... letu {} retta {} stæin þenna {} æftiʀ {} ... ... Hann fell a Grikklandi.

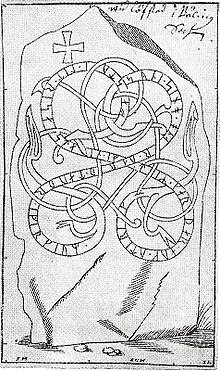

"[70]Runestone U 518 (location) is in the RAK style[72] and is raised on the southern side of a piny slope some 700 m (2,300 ft) north-east of the main building of the homestead Västra Ledinge.

[76] In 1887, the parishioners decided to extract both U 540 and U 541 from the church and with financial help from the Royal Swedish Academy of Letters, History and Antiquities the stones were removed and attached outside the northern wall.

[90][91] ikimuntrIngimundr' ukokþorþrÞorðr,* [iarlIarl' ukokuikibiarnVigbiorn(?)* lituletu' risaræisa* stainstæin' at]atikifastIngifast,* faþurfaður[* sinsinn,sturn*maþrstyrimaðr,'] sumsum' forfor' tiltil* girkhaGirkia' hutut,' sunsunn' ionhaIona(?),* ukok* atat* igulbiarnIgulbiorn.* inEnybiʀØpiʀ[* ristiristi.

Olof Celsius noted that Peringskiöld had been wrong and that the stone was intact, although it gives an impression of being split in two,[97] and the same observation was made by Richard Dybeck in 1866.

stniltr ' lit * rita stain þino ' abtiʀ ' uiþbiurn ' krikfara ' buanta sin kuþ hialbi hos| |salu| |uk| |kuþs u muþiʀ osmuntr kara sun markaþi{} Stæinhildr {} let {} retta stæin þenna {} æptiʀ {} Viðbiorn {} Grikkfara, {} boanda sinn.

(He) steered a cargo-ship; he came to Greek harbours; died at home ... ... cut the runes ..."* liutrLiutr: sturimaþrstyrimaðr* ritiretti: stainstæin: þinsaþennsa: aftiræftiʀ: sunusunu* sinasina.: saSahithet: akiAki,: simssem'sutiutifursfors.: sturþ(i)Styrði* -(n)ari[k]nærri,* kuamkvam*: hnhannkrikGrikkia.* : hafnirHæfniʀ,: haimahæimatudo: ...-mu-.........(k)(a)(r)......(i)ukhiogg(?)(r)(u)-(a)ru[n]aʀ(?)* ......

*] [fastui * lit * risa stain * iftiʀ * karþar * auk * utirik suni * sino * onar uarþ tauþr i girkium *]Fastvi {} let {} ræisa stæin {} æftiʀ {} Gærðar {} ok {} Otrygg, syni {} sina.

)× iukhiogg× uln⟨uln⟩.×] [+] ui—(a)n [× (b)a-]iʀ × (i)þrn + ʀftʀh × fraitʀn × bruþur × [is](ʀ)n × þuþʀ × kʀkum (×) [þulʀ × iuk × uln ×]{} Vi[st]æinn {} ⟨ba-iʀ⟩ {} ⟨iþrn⟩ {} æftiʀ {} Frøystæin, {} broður {} sinn, {} dauðr [i] Grikkium.

: ansuar : auk : ern... ... [: faþur sin : han : enta]þis : ut i : krikum (r)uþr : —...unk——an——{} Andsvarr {} ok {} Ærn... ... {} faður sinn.

George Stephens reported in 1857 that its former position had been on a barrow at a small path near Ryckesta, but that it had been moved in 1830 to the avenue of the manor Täckhammar and reerected on a wooded slope some 14 paces from the entrance to the highway.

This analysis was accepted by Brate & Wessén although they noted that the name contains ʀ instead of the expected r,[118] whereas the Rundata corpus gives the slightly different form Þryðríkr.

[28] He was one of the sons of the "good man" Gulli, and the runestone describes a situation that may have been common for Scandinavian families at this time: the stone was made on the orders of Özur's niece, Þorgerðr, in memory of her uncles who were all dead.

[137] * þukirÞorgærðr(?)* resþiræisþi* stinstæin* þansiþannsi* eftiʀæftiʀ* asurAssur,* sensinn* muþur*bruþurmoðurbroður* sinsinn,* iaʀeʀ* eataþisændaðis* austraustr* ii* krikumGrikkium.

* * þukir * resþi * stin * þansi * eftiʀ * asur * sen * muþur*bruþur * sin * iaʀ * eataþis * austr * i * krikum *{} Þorgærðr(?)

The brave valiant man Ásmundr fell at Fœri; Ôzurr met his end in the east in Greece; Halfdan was killed at Holmr (Bornholm?

[142] : askataAsgauta/Askatla: aukok: kuþmutrGuðmundr: þauþau: risþuræisþu: kumlkumbl: þ[i](t)aþetta: iftiʀæftiʀ: u-aukO[ddl]aug(?),: iaʀeʀ: buki|byggi|ii: haþistaþumHaðistaðum.: anHann: uaʀvaʀ: buntibondi: kuþrgoðr,: taþrdauðr: ii: ki[(r)]k[(i)(u)(m)]Grikkium(?).

Djurklou considered its placement to be unhelpful because a part of the runic band was buried in the soil, so he commanded an honourable farmer to select a group of men and remove the stone from the wall.

In 1922, the runologist Kinander learnt from a local farmer that some 40 years earlier, the runestone had been seen walled into a bridge that was part of the country road, and the inscription had been upwards.

[151] It has been dated to the late 11th century,[152] and although the interpretation of its message is uncertain, scholars have generally accepted von Friesen's analysis that it commemorates the travels of two Gotlanders to Greece, Jerusalem, Iceland and the Muslim world (Serkland).

[153] The inscription created a sensation as it mentions four distant countries that were the targets of adventurous Scandinavian expeditions during the Viking Age, but it also stirred some doubts as to its authenticity.

Moreover, v Friesen commented that there could be no expert on Old Swedish that made a forgery while he correctly wrote krikiaʀ as all reference books of the time incorrectly told that the form was grikir.