Population exchange between Greece and Turkey

It involved at least 1.6 million people (1,221,489 Greek Orthodox from Asia Minor, Eastern Thrace, the Pontic Alps and the Caucasus, and 355,000–400,000 Muslims from Greece),[2] most of whom were forcibly made refugees and de jure denaturalized from their homelands.

On 16 March 1922, Turkish Minister of Foreign Affairs Yusuf Kemal Tengrişenk stated that "[t]he Ankara Government was strongly in favour of a solution that would satisfy world opinion and ensure tranquillity in its own country", and that "[i]t was ready to accept the idea of an exchange of populations between the Greeks in Asia Minor and the Muslims in Greece".

[3][4] Eventually, the initial request for an exchange of population came from Eleftherios Venizelos in a letter he submitted to the League of Nations on 16 October 1922, following Greece's defeat in the Greco-Turkish War and two days after their accession of the Armistice of Mudanya.

The request intended to normalize relations de jure, since the majority of surviving Greek inhabitants of Turkey had fled from recent massacres to Greece by that time.

This was due to events that had a significant impact on the country's demographic structure, such as the First World War, the genocide of Assyrians, Greeks, and Armenians, and the population exchange between Greece and Turkey in 1923.

On January 31, 1917, the Chancellor of Germany, allied with the Ottomans during World War I, was reporting that: The indications are that the Turks plan to eliminate the Greek element as enemies of the state, as they did earlier with the Armenians.

The surviving Christian minorities within Turkey, particularly the Armenians and the Greeks, had sought protection from the Allies and thus continued to be seen as an internal problem, and as an enemy, by the Turkish National Movement.

By the time of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk's capture of Smyrna in September 1922, over a million Greek orthodox Ottoman subjects had fled their homes in Turkey.

Two weeks after the treaty, the Allied Powers turned over Istanbul to the Nationalists, marking the final departure of occupation armies from Anatolia and provoking another flight of Christian minorities to Greece.

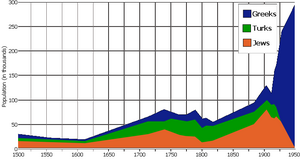

With this newly annexed population, the proportion of non-Greek minority groups in Greece rose to 13%, and following the end of the First World War, it had increased to 20%.

The government in Ankara still expected a thousand "Turkish-speakers" from the Çamëria to arrive in Turkey for settlement in Erdek, Ayvalık, Menteşe, Antalya, Senkile, Mersin, and Adana.

Ultimately, the Greek authorities decided to deport thousands of Muslims from Thesprotia, Larissa, Langadas, Drama, Edessa, Serres, Florina, Kilkis, Kavala, and Thessaloniki.

As the first official high commissioner for refugees, Nansen proposed and supervised the exchange, taking into account the interests of Greece, Turkey, and West European powers.

Because of the unanimous decision by the Greek and Turkish governments that minority protection would not suffice to ameliorate ethnic tensions after the First World War, population exchange was promoted as the only viable option.

[32]: 823–847 According to representatives from Ankara, the "amelioration of the lot of the minorities in Turkey' depended 'above all on the exclusion of every kind of foreign intervention and of the possibility of provocation coming from outside'.

When the Commission arrived in Greece, the Greek government had already settled provisionally 72,581 farming families, almost entirely in Macedonia, where the houses abandoned by the exchanged Muslims and the fertility of the land made their establishment practicable and auspicious.

In fact, Caglar Keyder noted that "what this drastic measure [Greek-Turkish population exchange] indicates is that during the war years Turkey lost ... [around 90 percent of the pre-war] commercial class, such that when the Republic was formed, the bureaucracy found itself unchallenged".

[36] The arrival of so many people in so short a period of time imposed significant costs on the Greek economy such as building housing and schools, importing enough food, providing health care, etc.

[39] Regardless of whether they settled in urban or rural areas, the vast majority of the refugees arrived in Greece impoverished and often sickly, placing enormous demands on the Greek health care system.

[43] Demagogic politicians quite consciously stoked tensions, portraying refugees as a parasitical class who by their very existence were overwhelming public services, as a way to gain votes.

[41] Aristeidis Stergiadis, the Greek High Commissioner in Smyrna remarked in August 1922 as the Turkish Army advanced upon the city: "Better that they stay here and be slain by Kemal [Ataturk], because if they go to Athens they will overthrow everything".

The impoverished slum districts of Thessaloniki where the refugees were concentrated became strongholds of the Greek Communist Party in the Great Depression together with the rural areas of Macedonia where tobacco farming was the main industry.

On the other hand, the Greek populations that left were skilled workers who engaged in transnational trade and business, as per previous capitulations policies of the Ottoman Empire.

Nonetheless, religion was utilized as a legitimizing factor or a "safe criterion" in marking ethnic groups as Turkish or as Greek in the population exchange.

However, due to the heterogeneous nature of these former Ottoman lands, many other ethnic groups posed social and legal challenges to the terms of the agreement for years after its signing.

[51] In Thessaloniki, which had the largest Jewish population in the Balkans, competition emerged between the Sephardic Jews who spoke Ladino and the refugees for jobs and businesses.

[53] A group of refugee merchants in Thessaloniki founded the republican and anti-Semitic EEE (Ethniki Enosis Ellados-National Union of Greece) party in 1927 to press for the removal of the Jews from the city, whom they saw as economic competitors.

The Ankara Government, led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, moved swiftly to implement its nationalist programme, which did not allow for the presence of significant non-Turkish minorities in Western Anatolia.

[63] The Turks and other Muslims of Western Thrace were exempted from this transfer as were the Greeks of Constantinople (Istanbul) and the Aegean Islands of Imbros (Gökçeada) and Tenedos (Bozcaada).

Countries also faced other practical challenges: for example, even decades after, one could notice certain hastily developed parts of Athens, residential areas that had been quickly erected on a budget while receiving the fleeing Asia Minor population.

Demotic Greek speakers in yellow, Pontic Greek speakers in orange, and Cappadocian Greek speakers in green. Towns are shown as dots, and cities as squares. [ 27 ]