Ancient Greek temple

This might include many subsidiary buildings, sacred groves or springs, animals dedicated to the deity, and sometimes people who had taken sanctuary from the law, which some temples offered, for example to runaway slaves.

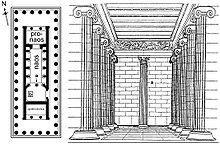

This led to the development of the peripteros, with a frontal pronaos (porch), mirrored by a similar arrangement at the back of the building, the opisthodomos, which became necessary for entirely aesthetic reasons.

Their self-aggrandisation, rivalry, desires to stabilise their spheres of influence, as well as the increasing conflict with Rome (partially played out in the field of culture), combined to release much energy into the revival of complex Greek temple architecture.

This limitation to smaller structures led to the development of a special form, the pseudoperipteros, which uses engaged columns along the naos walls to produce the illusion of a peripteral temple.

[27] The edicts of Theodosius I and his successors on the throne of the Roman Empire, banning pagan cults, led to the gradual closure of Greek temples, or their conversion into Christian churches.

There is no door connecting the opisthodomos with the naos; its existence is necessitated entirely by aesthetic considerations: to maintain the consistency of the peripteral temple and to ensure its visibility from all sides, the execution of the front has to be repeated at the rear.

The complex formed by the naos, pronaos, opisthodomos and possibly the adyton is enclosed on all four sides by the peristasis, usually a single row, rarely a double one, of columns.

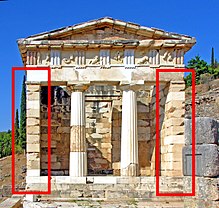

In contrast, the term peripteros or peripteral designates a temple surrounded by ptera (colonnades) on all four sides, each usually formed by a single row of columns.

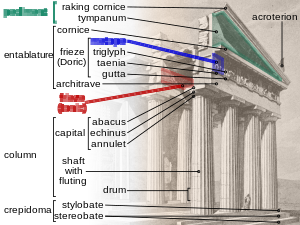

With the introduction of stone architecture, the protection of the porticos and the support of the roof construction was moved upwards to the level of the geison, depriving the frieze of its structural function and turning it into an entirely decorative feature.

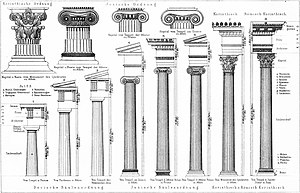

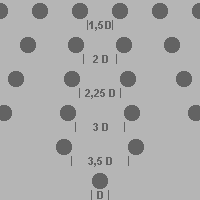

Columns could reach a height of 20 m. To design such large architectural bodies harmoniously, a number of basic aesthetic principles were developed and tested already on the smaller temples.

In the original temples, this would have been subject entirely to practical necessities, and always based on axial links between naos walls and columns, but the introduction of stone architecture broke that connection.

Only after a long phase of developments did the architects choose the alignment of the outer wall face with the adjacent column axis as the obligatory principle for Doric temples.

[29] To loosen up the mathematical strictness and to counteract distortions of human visual perception, a slight curvature of the whole building, hardly visible with the naked eye, was introduced.

In spite of the immense extra effort entailed in this perfection, the Parthenon, including its sculptural decoration, was completed in the record time of sixteen years (447 to 431).

The roofs were crowned by acroteria, originally in the form of elaborately painted clay disks, from the 6th century onwards as fully sculpted figures placed on the corners and ridges of the pediments.

Exceptions are found in the temples of Apollo at Bassae and of Athena at Tegea, where the southern naos wall had a door, potentially allowing more light into the interior.

[35] It was typically necessary to make a sacrifice or gift, and some temples restricted access either to certain days of the year, or by class, race, gender (with either men or women forbidden), or even more tightly.

Garlic-eaters were forbidden in one temple, in another women unless they were virgins; restrictions typically arose from local ideas of ritual purity or a perceived whim of the deity.

Hellenistic monarchs could appear as private donors in cities outside their immediate sphere of influence and sponsor public buildings, as exemplified by Antiochos IV, who ordered the rebuilding of the Olympieion at Athens.

[43] The increasing monumentalisation of stone buildings, and the transfer of the wooden roof construction to the level of the geison removed the fixed relationship between the naos and the peristasis.

This relationship between the axes of walls and columns, almost a matter of course in smaller structures, remained undefined and without fixed rules for nearly a century: the position of the naos "floated" within the peristasis.

In the light of this mutual influence it is not surprising that in the late 4th century BC temple of Zeus at Nemea, the front is emphasised by a pronaos two intercolumniations deep, while the opisthodomos is suppressed.

For example, innovations regarding the construction of the entablature developed in the west allowed the spanning of much wider spaces than before, leading to some very deep peristaseis and broad naoi.

The early temples also show no concern for the typical Doric feature of visibility from all sides, they regularly lack an opisthodomos; the peripteros only became widespread in the area in the 4th century.

The peristasis was of equal depth on all sides, eliminating the usual emphasis on the front, an opisthodomos, integrated into the back of the naos, is the first proper example in Ionic architecture.

This small ionic prostyle temple had engaged columns along the sides and back, the peristasis was thus reduced to a mere hint of a full portico facade.

All of these details suggest an Alexandrian workshop, since Alexandria showed the greatest tendency to combine Doric entablatures with Corinthian capitals and to do without the plinth under Attic bases.

The Corinthian order permitted a considerable increase of the material and technical effort invested in a building, which made its use attractive for the purposes of royals' self-aggrandisement.

The demise of the Hellenistic monarchies and the increasing power of Rome and her allies placed mercantile elites and sanctuary administrations in the positions of building sponsors.

The small temple of Apollo Epicurius at Bassae survived in a rural location with most of its columns and main architrave blocks in place, amid a jumble of fallen stone.