Chinese painting

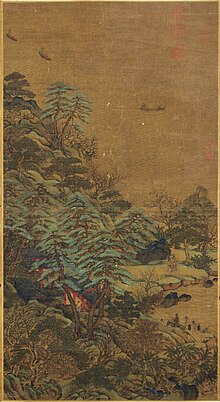

In the north, artists such as Jing Hao, Li Cheng, Fan Kuan, and Guo Xi painted pictures of towering mountains, using strong black lines, ink wash, and sharp, dotted brushstrokes to suggest rough stone.

In the south, Dong Yuan, Juran, and other artists painted the rolling hills and rivers of their native countryside in peaceful scenes done with softer, rubbed brushwork.

Original writings by famous calligraphers have been greatly valued throughout China's history and are mounted on scrolls and hung on walls in the same way that paintings are.

Even when these artists illustrated Confucian moral themes – such as the proper behavior of a wife to her husband or of children to their parents – they tried to make the figures graceful.

The emphasis laid upon landscape was grounded in Chinese philosophy; Taoism stressed that humans were but tiny specks in the vast and greater cosmos, while Neo-Confucianist writers often pursued the discovery of patterns and principles that they believed caused all social and natural phenomena.

[8] Artists mastered the formula of intricate and realistic scenes placed in the foreground, while the background retained qualities of vast and infinite space.

[12] Ever since the Southern and Northern dynasties (420–589), painting had become an art of high sophistication that was associated with the gentry class as one of their main artistic pastimes, the others being calligraphy and poetry.

Anthony J. Barbieri-Low, a professor of early Chinese history at the University of California, Santa Barbara, points out that Song scholars' appreciation of art created by their peers was not extended to those who made a living simply as professional artists:[15] During the Northern Song (960–1126 CE), a new class of scholar-artists emerged who did not possess the tromp l'œil skills of the academy painters nor even the proficiency of common marketplace painters.

The scholar-artists considered that painters who concentrated on realistic depictions, who employed a colorful palette, or, worst of all, who accepted monetary payment for their work were no better than butchers or tinkers in the marketplace.

One of the greatest landscape painters given patronage by the Song court was Zhang Zeduan (1085–1145), who painted the original Along the River During the Qingming Festival scroll, one of the most well-known masterpieces of Chinese visual art.

[16] During the Southern Song period (1127–1279), court painters such as Ma Yuan and Xia Gui used strong black brushstrokes to sketch trees and rocks and pale washes to suggest misty space.

Jieziyuan Huazhuan (Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden), a five-volume work first published in 1679, has been in use as a technical textbook for artists and students ever since.

During the early Qing dynasty (1644–1911), painters known as Individualists rebelled against many of the traditional rules of painting and found ways to express themselves more directly through free brushwork.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, great commercial cities such as Yangzhou and Shanghai became art centers where wealthy merchant-patrons encouraged artists to produce bold new works.

Prominent Chinese artists who studied Western painting include Li Tiefu, Yan Wenliang, Xu Beihong, Lin Fengmian, Fang Ganmin and Liu Haisu.

Following the model of the Soviet Union, the early PRC endorsed historical oil painting and the state commissioned many artistic works in this style to represent the new nation by depicting major battles and other events leading the country's proclamation.

[11]: 137 The New Guohua Campaign asked painters to modernize the traditional style (which had historically been exclusive to China's ruling class) to portray the PRC's landscape.

One of the representative artists is Wei Dong who drew inspirations from eastern and western sources to express national pride and arrive at personal actualization.

A Thousand Miles of Rivers and Mountains by Wang Ximeng, celebrates the imperial patronage and builds up a bridge that ties the later emperors, Huizong, Shenzong with their ancestors, Taizu and Taizong.

Combining richness bright blue and turquoise pigments heritage from Tang dynasty with the vastness and solemn space and mountains from Northern Song, the scroll is a perfect representation of imperial power and aesthetic taste of the aristocrats.

The bridge is interpreted to have symbolic meaning that represents the road which hermits depart from capital city and their official careers and go back to the natural world.

[26] During Song dynasty, paintings with themes ranging from animals, flower, landscape and classical stories, are used as ornaments in imperial palace, government office and elites' residence for multiple purposes.

During Tang dynasty reign of Emperor Xianzong (805–820), the west wall of the xueshi yuan was covered by murals depicting dragon-like mountain scene.

The mural painted by Song artist Dong yu, closely followed the tradition of the Tang dynasty in depicting the misty sea surrounding the immortal mountains.

In his painting, Early Spring, the strong branches of the trees reflects the life force of the living creatures and implying the emperor's benevolent rule.

A hand roll Exemplary Womenby Ku Kai Zhi, a six Dynasty artist, depicted woman characters who may be a wife, a daughter or a widow.

Similar to another early Southern Song painter, Zhou Boju, both artists glorified their patrons by presenting the gigantic empire images in blue and green landscape painting.

The Taoism ideology of forgetfulness, self-cultivation, harmonizing with nature world, and purifying soul by entering the isolated mountains to mediate and seek medicine herbs create the scene of landscape painting.

For example, in Ku Kai-chih's "Nymph of the river" scroll and "The Admonitions of the Court Preceptress", audience are able to read narrative description and text accompanied by visualized images.

This assimilation is also recorded in a poem by poet from the Six Dynasties period who pointed out that the beauty and numinosity of the mountain can elevate the spiritual connection between human being and the spirits.