Distributed-element filter

The filter design is usually concerned only with inductance and capacitance, but because of this mixing of elements they cannot be treated as separate "lumped" capacitors and inductors.

These discontinuities present a reactive impedance to a wavefront travelling down the line, and these reactances can be chosen by design to serve as approximations for lumped inductors, capacitors or resonators, as required by the filter.

[4] The development of distributed-element filters was spurred on by the military need for radar and electronic counter measures during World War II.

When the war ended, the technology found applications in the microwave links used by telephone companies and other organisations with large fixed-communication networks, such as television broadcasters.

Nowadays the technology can be found in several mass-produced consumer items, such as the converters (figure 1 shows an example) used with satellite television dishes.

On the other hand, antenna structure dimensions are usually comparable to λ in all frequency bands and require the distributed-element model.

[11] Mason and Sykes' work was focused on the formats of coaxial cable and balanced pairs of wires – the planar technologies were not yet in use.

[16] The difficulty with Richards' transformation from the point of view of building practical filters was that the resulting distributed-element design invariably included series connected elements.

He published a set of transformations known as Kuroda's identities in 1955, but his work was written in Japanese and it was several years before his ideas were incorporated into the English-language literature.

In 1957, Leo Young at Stanford Research Institute published a method for designing filters which started with a distributed-element prototype.

[21] This caught on rapidly, and Barrett's stripline soon had fierce commercial competition from rival planar formats, especially triplate and microstrip.

[25] Much of this work was published by the group at Stanford led by George Matthaei, and also including Leo Young mentioned above, in a landmark book which still today serves as a reference for circuit designers.

[30] More recent research has concentrated on new or variant mathematical classes of the filters, such as pseudo-elliptic, while still using the same basic topologies, or with alternative implementation technologies such as suspended stripline and finline.

[31] The initial non-military application of distributed-element filters was in the microwave links used by telecommunications companies to provide the backbone of their networks.

[33] An emerging application is in superconducting filters for use in the cellular base stations operated by mobile phone companies.

Over a narrow range of frequencies, a stub can be used as a capacitor or an inductor (its impedance is determined by its length) but over a wide band it behaves as a resonator.

Stubs can also be used in conjunction with impedance transformers to build more complex filters and, as would be expected from their resonant nature, are most useful in band-pass applications.

[40] Coupled lines (figures 3(c-e)) can also be used as filter elements; like stubs, they can act as resonators and likewise be terminated short-circuit or open-circuit.

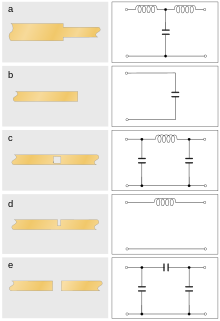

The filter consists of alternating sections of high-impedance and low-impedance lines which correspond to the series inductors and shunt capacitors in the lumped-element implementation.

In such cases, each element of the filter is λ/4 in length (where λ is the wavelength of the main-line signal to be blocked from transmission into the DC source) and the high-impedance sections of the line are made as narrow as the manufacturing technology will allow in order to maximise the inductance.

As well as the planar form shown, this structure is particularly well suited for coaxial implementations with alternating discs of metal and insulator being threaded on to the central conductor.

A stub that is narrow in comparison to λ can be taken as being connected on its centre-line and calculations based on that assumption will accurately predict filter response.

For a wide stub, however, calculations that assume the side branch is connected at a definite point on the main line leads to inaccuracies as this is no longer a good model of the transmission pattern.

It is particularly suitable for planar formats, is easily implemented with printed circuit technology and has the advantage of taking up no more space than a plain transmission line would.

The limitation of this topology is that performance (particularly insertion loss) deteriorates with increasing fractional bandwidth, and acceptable results are not obtained with a Q less than about 5.

This topology is straightforward to implement in planar technologies, but also particularly lends itself to a mechanical assembly of lines fixed inside a metal case.

As with the parallel-coupled line filter, the advantage of a mechanical arrangement that does not require insulators for support is that dielectric losses are eliminated.

The chief advantage of this design is that the upper stopband can be made very wide, that is, free of spurious passbands at all frequencies of interest.

A filter with similar properties can be constructed with λ/4 open-circuit stubs placed in series with the line and coupled together with λ/4 impedance transformers, although this structure is not possible in planar technologies.

Even structures that seem to have an "obvious" high-pass topology, such as the capacitive gap filter of figure 8, turn out to be band-pass when their behaviour for very short wavelengths is considered.

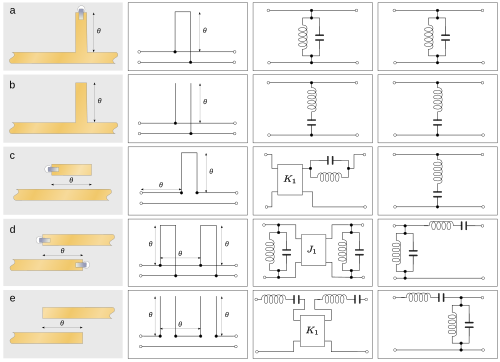

- A short-circuit stub in parallel with the main line.

- An open-circuit stub in parallel with the main line.

- A short-circuit line coupled to the main line.

- Coupled short-circuited lines.

- Coupled open-circuited lines.

represents a strap through the board making connection with the ground plane underneath.

represents a strap through the board making connection with the ground plane underneath.

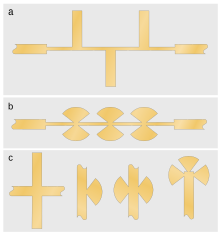

- Standard stubs on alternating sides of main line λ/4 apart.

- Similar construction using butterfly stubs.

- Various forms of stubs, respectively, doubled stubs in parallel, radial stub, butterfly stub (paralleled radial stubs), clover-leaf stub (triple paralleled radial stubs).