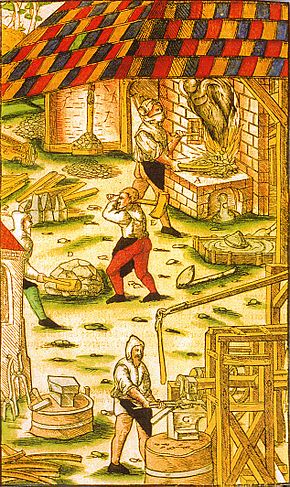

Hammer mill

[2] These mills, which were original driven by water wheels, but later also by steam power, became increasingly common as tools became heavier over time and therefore more difficult to manufacture by hand.

The hammer mills smelted iron ore using charcoal in so-called bloomeries (Georgius Agricola 1556, Rennherden, Rennfeuer or Rennofen: from Rinnen = "rivulets" of slag or Zrennherd from Zerrinnen = "to melt away").

In these smelting ovens, which were equipped with bellows also driven by water power, the ore was melted into a glowing clump of soft, raw iron, fluid slag and charcoal remnants.

The iron was not fluid as it would be in a modern blast furnace, but remained a doughy, porous lump mainly due to the presence of liquid slag.

The Upper Palatinate was one of the European centres of iron smelting and its many hammer mills led to its nickname as the "Ruhrgebiet of the Middle Ages".

Steelworkers in Thiers, France used hammer mills, powered by the Durolle River in the Vallée des Rouets, for the production of knives and other cutlery until the middle of the 19th century.

It runs for 120 kilometres, linking numerous historical industrial sites, which represent several centuries, with cultural and natural monuments.