Blast furnace

The end products are usually molten metal and slag phases tapped from the bottom, and waste gases (flue gas) exiting from the top of the furnace.

[2] The downward flow of the ore along with the flux in contact with an upflow of hot, carbon monoxide-rich combustion gases is a countercurrent exchange and chemical reaction process.

According to this broad definition, bloomeries for iron, blowing houses for tin, and smelt mills for lead would be classified as blast furnaces.

It reacts with calcium oxide (burned limestone) and forms silicates, which float to the surface of the molten pig iron as slag.

As the material travels downward, the counter-current gases both preheat the feed charge and decompose the limestone to calcium oxide and carbon dioxide: The calcium oxide formed by decomposition reacts with various acidic impurities in the iron (notably silica), to form a fayalitic slag which is essentially calcium silicate, CaSiO3:[8] As the iron(II) oxide moves down to the area with higher temperatures, ranging up to 1200 °C degrees, it is reduced further to iron metal: The carbon dioxide formed in this process is re-reduced to carbon monoxide by the coke: The temperature-dependent equilibrium controlling the gas atmosphere in the furnace is called the Boudouard reaction: The pig iron produced by the blast furnace has a relatively high carbon content of around 4–5% and usually contains too much sulphur, making it very brittle, and of limited immediate commercial use.

The efficiency of the process was further enhanced by the practice of preheating the combustion air (hot blast), patented by Britishh inventor James Beaumont Neilson in 1828.

Originally it was thought that the Chinese started casting iron right from the beginning, but this theory has since been debunked[clarification needed] by the discovery of 'more than ten' iron digging implements found in the tomb of Duke Jing of Qin (d. 537 BC), whose tomb is located in Fengxiang County, Shaanxi (a museum exists on the site today).

[24][25] The primary advantage of the early blast furnace was in large scale production and making iron implements more readily available to peasants.

The oldest known blast furnaces in the West were built in Durstel in Switzerland, the Märkische Sauerland in Germany, and at Lapphyttan in Sweden, where the complex was active between 1205 and 1300.

[36] The Caspian region may also have been the source for the design of the furnace at Ferriere, described by Filarete,[37] involving a water-powered bellows at Semogo in Valdidentro in northern Italy in 1226.

[42] At Laskill, an outstation of Rievaulx Abbey and the only medieval blast furnace so far identified in Britain, the slag produced was low in iron content.

[43][44][45] Its date is not yet clear, but it probably did not survive until Henry VIII's Dissolution of the Monasteries in the late 1530s, as an agreement (immediately after that) concerning the "smythes" with the Earl of Rutland in 1541 refers to blooms.

Due to the increased demand for iron for casting cannons, the blast furnace came into widespread use in France in the mid 15th century.

From there, they spread first to the Pays de Bray on the eastern boundary of Normandy and from there to the Weald of Sussex, where the first furnace (called Queenstock) in Buxted was built in about 1491, followed by one at Newbridge in Ashdown Forest in 1496.

[57][58][59] However, in many areas of the world charcoal was cheaper while coke was more expensive even after the Industrial Revolution: e. g., in the US charcoal-fueled iron production fell in share to about a half ca.

[62] Darby's original blast furnace has been archaeologically excavated and can be seen in situ at Coalbrookdale, part of the Ironbridge Gorge Museums.

Within a few years of the introduction, hot blast was developed to the point where fuel consumption was cut by one-third using coke or two-thirds using coal, while furnace capacity was also significantly increased.

According to Global Energy Monitor, the blast furnace is likely to become obsolete to meet climate change objectives of reducing carbon dioxide emission,[72] but BHP disagrees.

[73] The oxygen blast furnace (OBF) process, developed from the 1970s to the 1990s, has been extensively studied theoretically because of the potentials of promising energy conservation and CO2 emission reduction.

Modern furnaces are equipped with an array of supporting facilities to increase efficiency, such as ore storage yards where barges are unloaded.

Rail-mounted scale cars or computer controlled weight hoppers weigh out the various raw materials to yield the desired hot metal and slag chemistry.

Some of these bell-less systems also implement a discharge chute in the throat of the furnace (as with the Paul Wurth top) in order to precisely control where the charge is placed.

[85] The iron making blast furnace itself is built in the form of a tall structure, lined with refractory brick, and profiled to allow for expansion of the charged materials as they heat during their descent, and subsequent reduction in size as melting starts to occur.

[82] The "casthouse" at the bottom half of the furnace contains the bustle[clarification needed] pipe, water cooled copper tuyeres and the equipment for casting the liquid iron and slag.

[82] The exhaust gasses of a blast furnace are generally cleaned in the dust collector – such as an inertial separator, a baghouse, or an electrostatic precipitator.

[93] Using hydrogen gas as a reductant to produce DRI (so called H2-DRI) from iron ore, which is then used as a feedstock for an EAF provides a technologically feasible, low emission alternative to blast furnaces.

By treating BFG with carbon capture technology prior to use for heat exchange and energy recovery within the plant, a portion of these emissions can be abated.

[95] At the time, this would have increased steel production costs by 15–20%,[88] [citation needed] presenting a barrier to decarbonisation for steelmakers which typically operate with margins of 8–10%.

ULCOS (Ultra Low CO2 Steelmaking)[97] was a European programme exploring processes to reduce blast furnace emissions by at least 50%.

Technologies identified include carbon capture and storage (CCS) and alternative energy sources and reductants such as hydrogen, electricity and biomass.

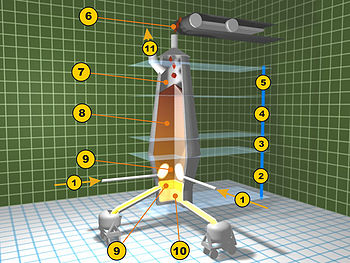

- Iron ore + limestone sinter

- Coke

- Elevator

- Feedstock inlet

- Layer of coke

- Layer of sinter pellets of ore and limestone

- Hot blast (around 1200 °C)

- Removal of slag

- Tapping of molten pig iron

- Slag pot

- Torpedo car for pig iron

- Dust cyclone for separation of solid particles

- Cowper stoves for hot blast

- Smoke stack

- Feed air for Cowper stoves (air pre-heaters)

- Powdered coal

- Coke oven

- Coke

- Blast furnace gas downcomer

- Hot blast from Cowper stoves

- Melting zone ( bosh )

- Reduction zone of ferrous oxide ( barrel )

- Reduction zone of ferric oxide ( stack )

- Pre-heating zone ( throat )

- Feed of ore, limestone, and coke

- Exhaust gases

- Column of ore, coke and limestone

- Removal of slag

- Tapping of molten pig iron

- Collection of waste gases