Classical Chinese

Starting in the 2nd century CE, use of Literary Chinese spread to the countries surrounding China, including Vietnam, Korea, Japan, and the Ryukyu Islands, where it represented the only known form of writing.

Each additionally developed systems of readings and annotations that enabled non-Chinese speakers to interpret Literary Chinese texts in terms of the local vernacular.

While not static throughout its history, its evolution has traditionally been guided by a conservative impulse: many later changes in the varieties of Chinese are not reflected in the literary form.

Due to millennia of this evolution, Literary Chinese is only partially intelligible when read or spoken aloud for someone only familiar with modern vernacular forms.

The Oxford Handbook of Classical Chinese Literature states that this adoption came mainly from diplomatic and cultural ties with China, while conquest, colonization, and migration played smaller roles.

[8] Unlike Latin and Sanskrit, historical Chinese language theory consisted almost exclusively of lexicography, as opposed to the study of grammar and syntax.

Additionally, words are generally not restricted to use as certain parts of speech: many characters may function as either a noun, verb, or adjective.

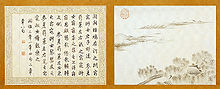

[14] Beyond differences in grammar and vocabulary, Classical Chinese can be distinguished by its literary qualities: an effort to maintain parallelism and rhythm is typical, even in prose works.

Prior to the literary revolution in China that began with the 1919 May Fourth Movement, prominent examples of vernacular Chinese literature include the 18th-century novel Dream of the Red Chamber.

However, even with knowledge of its grammar and vocabulary, works in Literary Chinese can be difficult for native vernacular speakers to understand, due to its frequent allusions and references to other historical literature, as well as the extremely laconic style.

Japan is the only country that maintains the tradition of creating Literary Chinese poetry based on Tang-era tone patterns.

As the imperial examination system required the candidate to compose poetry in the shi genre, pronunciation in non-Mandarin speaking parts of China such as Zhejiang, Guangdong and Fujian is either based on everyday speech, such as in Standard Cantonese, or is based on a special set of pronunciations borrowed from Classical Chinese, such as in Southern Min.

In practice, all varieties of Chinese combine the two extremes of pronunciation: that according to a prescribed system, versus that based on everyday speech.

However, some modern Chinese varieties have certain phonological characteristics that are closer to the older pronunciations than others, as shown by the preservation of certain rhyme structures.

The poem underlines how language had become impractical for modern speakers: when spoken aloud, Literary Chinese is largely incomprehensible.

Romanizations have been devised to provide distinct spellings for Literary Chinese words, together with pronunciation rules for various modern varieties.