Pinyin

Matteo Ricci, a Jesuit missionary in China, wrote the first book that used the Latin alphabet to write Chinese, entitled Xizi Qiji (西字奇蹟; 'Miracle of Western Letters') and published in Beijing in 1605.

[1] Twenty years later, fellow Jesuit Nicolas Trigault published 'Aid to the Eyes and Ears of Western Literati' (西儒耳目資; Xīrú ěrmù zī)) in Hangzhou.

[3] During the late Qing, the reformer Song Shu (1862–1910) proposed that China adopt a phonetic writing system.

A student of the scholars Yu Yue and Zhang Taiyan, Song had observed the effect of the kana syllabaries and Western learning during his visits to Japan.[which?]

Zhou, often called "the father of pinyin",[5][6][7][8] worked as a banker in New York when he decided to return to China to help rebuild the country after the People's Republic was established.

[5] Hanyu Pinyin incorporated different aspects from existing systems, including Gwoyeu Romatzyh (1928), Latinxua Sin Wenz (1931), and the diacritics from bopomofo (1918).

A revised Pinyin scheme was proposed by Wang Li, Lu Zhiwei and Li Jinxi, and became the main focus of discussion among the group of Chinese linguists in June 1956, forming the basis of Pinyin standard later after incorporating a wide range of feedback and further revisions.

[10] The first edition of Hanyu Pinyin was approved and officially adopted at the Fifth Session of the 1st National People's Congress on 11 February 1958.

It was then introduced to primary schools as a way to teach Standard Chinese pronunciation and used to improve the literacy rate among adults.

[12]: 200 During the height of the Cold War the use of pinyin system over Wade–Giles and Yale romanizations outside of China was regarded as a political statement or identification with the mainland Chinese government.

[14][15] In 2001, the Chinese government issued the National Common Language Law, providing a legal basis for applying pinyin.

[16] Chinese phonology is generally described in terms of sound pairs of two initials (声母; 聲母; shēngmǔ) and finals (韵母; 韻母; yùnmǔ).

This is distinct from the concept of consonant and vowel sounds as basic units in traditional (and most other phonetic systems used to describe the Chinese language).

Previously, the practice varied among different passport issuing offices, with some transcribing as "LV" and "NV" while others used "LU" and "NU".

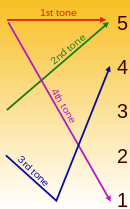

[20] In the pinyin system, four main tones of Mandarin are shown by diacritics: ā, á, ǎ, and à.

There is an exception for syllabic nasals like /m/, where the nucleus of the syllable is a consonant: there, the diacritic will be carried by a written dummy vowel.

That is, in the absence of a written nucleus the finals have priority for receiving the tone marker, as long as they are vowels; if not, the medial takes the diacritic.

This has drawn some criticism as it may lead to confusion when uninformed speakers apply either native or English assumed pronunciations to words.

However, this problem is not limited only to pinyin, since many languages that use the Latin alphabet natively also assign different values to the same letters.

In particular, Chinese characters retain semantic cues that help distinguish differently pronounced words in the ancient classical language that are now homophones in Mandarin.

Pinyin is not designed to transcribe varieties other than Standard Chinese, which is based on the phonological system of Beijing Mandarin.

Pinyin has also become the dominant Chinese input method in mainland China, in contrast to Taiwan, where bopomofo is most commonly used.

Families outside of Taiwan who speak Mandarin as a mother tongue use pinyin to help children associate characters with spoken words which they already know.

[32] Chinese families outside of Taiwan who speak some other language as their mother tongue use the system to teach children Mandarin pronunciation when learning vocabulary in elementary school.

Pinyin's role in teaching pronunciation to foreigners and children is similar in some respects to furigana-based books with hiragana letters written alongside kanji (directly analogous to bopomofo) in Japanese, or fully vocalised texts in Arabic.

The tone-marking diacritics are commonly omitted in popular news stories and even in scholarly works, as well as in the traditional Mainland Chinese Braille system, which is similar to pinyin, but meant for blind readers.

Alternatively, some touchscreen devices allow users to input characters graphically by writing with a stylus, with concurrent online handwriting recognition.

Chinese characters and words can be sorted for convenient lookup by their Pinyin expressions alphabetically,[36] according to their inherited order originating with the ancient Phoenicians.

The ruling Kuomintang (KMT) party resisted its adoption, preferring the system by then used in mainland China and internationally.

Attempts to make Hanyu Pinyin standard in Taiwan have had uneven success, with most place and proper names remaining unaffected, including all major cities.