Arabic diacritics

The Arabic script is a modified abjad, where all letters are consonants, leaving it up to the reader to fill in the vowel sounds.

It is, however, not uncommon for authors to add diacritics to a word or letter when the grammatical case or the meaning is deemed otherwise ambiguous.

As the normal Arabic text does not provide enough information about the correct pronunciation, the main purpose of tashkīl (and ḥarakāt) is to provide a phonetic guide or a phonetic aid; i.e. show the correct pronunciation for children who are learning to read or foreign learners.

Moreover, ḥarakāt are used in ordinary texts in individual words when an ambiguity of pronunciation cannot easily be resolved from context alone.

In art and calligraphy, ḥarakāt might be used simply because their writing is considered aesthetically pleasing.

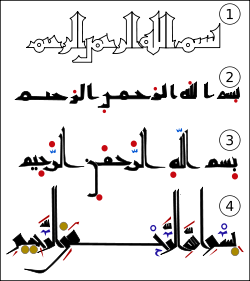

An example of a fully vocalised (vowelised or vowelled) Arabic from the Bismillah: بِسْمِ ٱللَّٰهِ ٱلرَّحْمَٰنِ ٱلرَّحِيمِ bismi l-lāhi r-raḥmāni r-raḥīm In the name of God, the All-Merciful, the Especially-Merciful.

There is some ambiguity as to which tashkīl are also ḥarakāt; the tanwīn, for example, are markers for both vowels and consonants.

The fatḥah ⟨فَتْحَة⟩ is a small diagonal line placed above a letter, and represents a short /a/ (like the /a/ sound in the English word "cat").

Although paired with a plain letter creates an open front vowel (/a/), often realized as near-open (/æ/), the standard also allows for variations, especially under certain surrounding conditions.

A similar "back" quality is undergone by other vowels as well in the presence of such consonants, however not as drastically realized as in the case of fatḥah.

A similar diagonal line below a letter is called a kasrah ⟨كَسْرَة⟩ and designates a short /i/ (as in "me", "be") and its allophones [i, ɪ, e, e̞, ɛ] (as in "Tim", "sit").

[4] When a kasrah is placed before a plain letter ⟨ﻱ⟩ (yā’), it represents a long /iː/ (as in the English word "steed").

The ḍammah ⟨ضَمَّة⟩ is a small curl-like diacritic placed above a letter to represent a short /u/ (as in "duke", shorter "you") and its allophones [u, ʊ, o, o̞, ɔ] (as in "put", or "bull").

[4] When a ḍammah is placed before a plain letter ⟨و⟩ (wāw), it represents a long /uː/ (like the 'oo' sound in the English word "swoop").

The dagger alif occurs in only a few words, but they include some common ones; it is seldom written, however, even in fully vocalised texts.

The maddah ⟨مَدَّة⟩ is a tilde-shaped diacritic, which can only appear on top of an alif (آ) and indicates a glottal stop /ʔ/ followed by a long /aː/.

It occurs in phrases and sentences (connected speech, not isolated/dictionary forms): Like the superscript alif, it is not written in fully vocalized scripts, except for sacred texts, like the Quran and Arabized Bible.

The i‘jām (إِعْجَام; sometimes also called nuqaṭ)[6] are the diacritic points that distinguish various consonants that have the same form (rasm), such as ⟨ص⟩ /sˤ/, ⟨ض⟩ /dˤ/.

Typically, Egyptians do not use dots under final yā’ (ي), which looks exactly like alif maqṣūrah (ى) in handwriting and in print.

The same unification of yā and alif maqṣūrā has happened in Persian, resulting in what the Unicode Standard calls "Arabic Letter Farsi Yeh", that looks exactly the same as yā in initial and medial forms, but exactly the same as alif maqṣūrah in final and isolated forms.

A superscript stroke known as jarrah, resembling a long fatħah, was used for a contracted (assimilated) sin.

[7] These signs, collectively known as ‘alāmātu-l-ihmāl, are still occasionally used in modern Arabic calligraphy, either for their original purpose (i.e. marking letters without i‘jām), or often as purely decorative space-fillers.

The small ک above the kāf in its final and isolated forms ⟨ك ـك⟩ was originally an ‘alāmatu-l-ihmāl that became a permanent part of the letter.

Previously this sign could also appear above the medial form of kāf, when that letter was written without the stroke on its ascender.

This is important to note, as without the diacritic present, there is no way to distinguish between tone markers and I‘jām i.e. dots that are used for purpose of phonetic distinctions of consonants.

[14][15] According to tradition, the first to commission a system of ḥarakāt was Ali who appointed Abu al-Aswad al-Du'ali for the task.

Abu al-Aswad devised a system of dots to signal the three short vowels (along with their respective allophones) of Arabic.

Another complication was that the i‘jām had been introduced by then, which, while they were short strokes rather than the round dots seen today, meant that without a color distinction the two could become confused.

It is useful to avoid ambiguity in applications such as Arabic machine translation, text-to-speech, and information retrieval.

[18][19] For Modern Standard Arabic, the state-of-the-art algorithm has a word error rate (WER) of 4.79%.