Health and safety hazards of nanomaterials

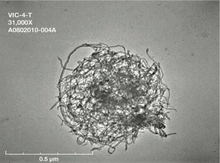

Of the possible hazards, inhalation exposure appears to present the most concern, with animal studies showing pulmonary effects such as inflammation, fibrosis, and carcinogenicity for some nanomaterials.

[1][2] Nanotechnology is the manipulation of matter at the atomic scale to create materials, devices, or systems with new properties or functions, with potential applications in energy, healthcare, industry, communications, agriculture, consumer products, and other sectors.

[3]: 1–3 As with any new technology, the earliest exposures are expected to occur among workers conducting research in laboratories and pilot plants, making it important that they work in a manner that is protective of their safety and health.

[4]: 2–6 [5]: 3–5 Ongoing verification of hazard controls can occur through monitoring of airborne nanomaterial concentrations using standard industrial hygiene sampling methods, and an occupational health surveillance program may be instituted.

Dust generation is affected by the particle shape, size, bulk density, and inherent electrostatic forces, and whether the nanomaterial is a dry powder or incorporated into a slurry or liquid suspension.

Factors such as size, shape, water solubility, and surface coating directly affect a nanoparticle's potential to penetrate the skin.

At this time, it is not fully known whether skin penetration of nanoparticles would result in adverse effects in animal models, although topical application of raw SWCNT to nude mice has been shown to cause dermal irritation, and in vitro studies using primary or cultured human skin cells have shown that carbon nanotubes can enter cells and cause release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, oxidative stress, and decreased viability.

Ingestion may also accompany inhalation exposure because particles that are cleared from the respiratory tract via the mucociliary escalator may be swallowed.

[8]: 12 There is concern that engineered carbon nanoparticles, when manufactured on an industrial scale, could pose a dust explosion hazard, especially for processes such as mixing, grinding, drilling, sanding, and cleaning.

However, for dusts of organic materials such as coal, flour, methylcellulose, and polyethylene, severity ceases to increase as the particle size is reduced below ~50 μm.

[5]: 17–18 One study found that the likelihood of an explosion but not its severity increases significantly for nanoscale metal particles, and they can spontaneously ignite under certain conditions during laboratory testing and handling.

Powders of nanomaterials are unlikely to present an unusual fire hazard as compared to their cardboard or plastic packaging, as they are usually produced in small quantities, with the exception of carbon black.

It increases the cost-effectiveness of occupational safety and health because hazard control methods are integrated early into the process, rather than needing to disrupt existing procedures to include them later.

For example, using a nanomaterial slurry or suspension in a liquid solvent instead of a dry powder will reduce dust exposure.

[3]: 11–12 Examples of local exhaust systems include fume hoods, gloveboxes, biosafety cabinets, and vented balance enclosures.

They include training on best practices for safe handling, storage, and disposal of nanomaterials, proper awareness of hazards through labeling and warning signage, and encouraging a general safety culture.

Some examples of good work practices include cleaning work spaces with wet-wiping methods or a HEPA-filtered vacuum cleaner instead of dry sweeping with a broom, avoiding handling nanomaterials in a free particle state, storing nanomaterials in containers with tightly closed lids.

Normal safety procedures such as hand washing, not storing or consuming food in the laboratory, and proper disposal of hazardous waste are also administrative controls.

[3]: 17–18 Other examples are limiting the time workers are handling a material or in a hazardous area, and exposure monitoring for the presence of nanomaterials.

[4]: 14–15 Personal protective equipment (PPE) must be worn on the worker's body and is the least desirable option for controlling hazards.

PPE normally used for typical chemicals are also appropriate for nanomaterials, including wearing long pants, long-sleeve shirts, and closed-toed shoes, and the use of safety gloves, goggles, and impervious laboratory coats.

[17] In the United States, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration requires fit testing and medical clearance for use of respirators,[18] and the Environmental Protection Agency requires the use of full face respirators with N100 filters for multi-walled carbon nanotubes not embedded in a solid matrix, if exposure is not otherwise controlled.

Organizations including GoodNanoGuide,[24] Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory,[25] and Safe Work Australia[26] have developed control banding tools that are specific for nanomaterials.

[4]: 31–33 The GoodNanoGuide control banding scheme is based only on exposure duration, whether the material is bound, and the extent of knowledge of the hazards.

[28] The NIOSH Manual of Analytical Methods includes guidance on electron microscopy of filter samples of carbon nanotubes and nanofibers,[29] and additionally some NIOSH methods developed for other chemicals can be used for off-line analysis of nanomaterials, including their morphology and geometry, elemental carbon content (relevant for carbon-based nanomaterials), and elemental makeup.

[4]: 34–35 The related topic of medical screening focuses on the early detection of adverse health effects for individual workers, to provide an opportunity for intervention before disease processes occur.

[4]: 34–35 It is recommended that a nanomaterial spill kit be assembled prior to an emergency and include barricade tape, nitrile or other chemically impervious gloves, an elastomeric full-facepiece respirator with P100 or N100 filters (fitted appropriately to the responder), adsorbent materials such as spill mats, disposable wipes, sealable plastic bags, walk-off sticky mats, a spray bottle with deionized water or another appropriate liquid to wet dry powders, and a HEPA-filtered vacuum.

[5]: 20–22 The General Duty Clause of the Occupational Safety and Health Act requires all employers to keep their workplace free of serious recognized hazards.

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health does not issue regulations, but conducts research and makes recommendations to prevent worker injury and illness.

[31] Under the REACH regulation, companies have the responsibility of collecting information on the properties and uses of substances that they manufacture or import at or above quantities of 1 ton per year, including nanomaterials.