Dutch East India Company

[6] Shares in the company could be purchased by any citizen of the Dutch Republic and subsequently bought and sold in open-air secondary markets (one of which became the Amsterdam Stock Exchange).

[7] The company possessed quasi-governmental powers, including the ability to wage war, imprison and execute convicts,[8] negotiate treaties, strike its own coins, and establish colonies.

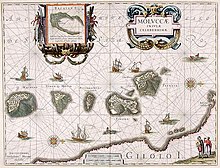

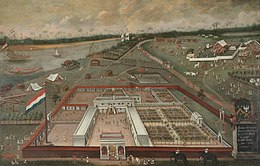

[12] Having been set up in 1602 to profit from the Malukan spice trade, the VOC established a capital in the port city of Jayakarta in 1619 and changed its name to Batavia (now Jakarta).

The monogram's versatility, flexibility, clarity, simplicity, symmetry, timelessness, and symbolism are considered notable characteristics of the VOC's professionally designed logo.

During the four-ship exploratory expedition by Frederick de Houtman in 1595 to Banten, the main pepper port of West Java, the crew clashed with both Portuguese and indigenous Javanese.

Houtman's expedition then sailed east along the north coast of Java, losing twelve crew members to a Javanese attack at Sidayu and killing a local ruler in Madura.

[23] East of Solor, on the island of Timor, Dutch advances were halted by an autonomous and powerful group of Portuguese Eurasians called the Topasses.

Investment in these expeditions was a very high-risk venture, not only because of the usual dangers of piracy, disease and shipwreck, but also because the interplay of inelastic demand and relatively elastic supply[e] of spices could make prices tumble, thereby ruining prospects of profitability.

[26] In 1602, the Dutch government followed suit, sponsoring the creation of a single "United East Indies Company" that was also granted monopoly over the Asian trade.

The governor-general effectively became the main administrator of the VOC's activities in Asia, although the Heeren XVII, a body of 17 shareholders representing different chambers, continued to officially have overall control.

The Straits of Malacca were strategic but became dangerous following the Portuguese conquest, and the first permanent VOC settlement in Banten was controlled by a powerful local ruler and subject to stiff competition from Chinese and English traders.

[23] In 1604, a second English East India Company voyage commanded by Sir Henry Middleton reached the islands of Ternate, Tidore, Ambon and Banda.

[35] Although this caused outrage in Europe and a diplomatic crisis, the English quietly withdrew from most of their Indonesian activities (except trading in Banten) and focused on other Asian interests.

Silver and copper from Japan were used to trade with the world's wealthiest empires, Mughal India and Qing China, for silk, cotton, porcelain, and textiles.

Through the seventeenth century VOC trading posts were also established in Persia, Bengal, Malacca, Siam, Formosa (now Taiwan), as well as the Malabar and Coromandel coasts in India.

This structural change in the commodity composition of the VOC's trade started in the early 1680s, after the temporary collapse of the EIC around 1683 offered an excellent opportunity to enter these markets.

This reflects the basic change in the VOC's circumstances that had occurred: it now operated in new markets for goods with an elastic demand, in which it had to compete on an equal footing with other suppliers.

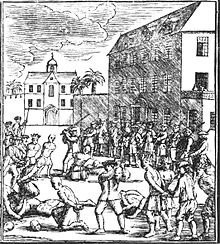

[60] This massacre of the Chinese was deemed sufficiently serious for the board of the VOC to start an official investigation into the Government of the Dutch East Indies for the first time in its history.

[63] Most of the possessions of the former VOC were subsequently occupied by Great Britain during the Napoleonic wars, but after the new United Kingdom of the Netherlands was created by the Congress of Vienna, some of these were restored to this successor state of the Dutch Republic by the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814.

Under the 1,143 tenderers were 39 Germans and no fewer than 301 from the Southern Netherlands (roughly present Belgium and Luxembourg, then under Habsburg rule), of whom Isaac le Maire was the largest subscriber with ƒ85,000.

[73][74][75] Initially the largest single shareholder in the VOC and a bewindhebber sitting on the board of governors, Le Maire apparently attempted to divert the firm's profits to himself by undertaking 14 expeditions under his own accounts instead of those of the company.

Since his large shareholdings were not accompanied by greater voting power, Le Maire was soon ousted by other governors in 1605 on charges of embezzlement, and was forced to sign an agreement not to compete with the VOC.

[76][77][78] In 1622, the history's first recorded shareholder revolt also happened among the VOC investors who complained that the company account books had been "smeared with bacon" so that they might be "eaten by dogs."

However, it unleashed a wave of criticism, since such romantic views about the Dutch Golden Age ignores the inherent historical associations with colonialism, exploitation and violence.

According to Marsely L. Kahoe in The Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art, "it is misleading to understand Batavia, as some scholars have, as representing a pragmatic and egalitarian order that was later corrupted by the colonial situation.

"[86] There was an extraordinarily high mortality rate among employees of the VOC due to shipwrecks, illnesses such as scurvy and dysentery, and clashes with rival trading companies and pirates.

Although the exact number remains uncertain, it is estimated that around 14,000 people were killed, enslaved or fled elsewhere, with only 1,000 Bandanese surviving in the islands, and were spread throughout the nutmeg groves as forced labourers.

War broke out again in 1673 and continued until 1677, when Khoikhoi resistance was destroyed by a combination of superior European weapons and Dutch manipulation of divisions among the local people.

[95] The VOC's operations (trading posts and colonies) produced not only warehouses packed with spices, coffee, tea, textiles, porcelain and silk, but also shiploads of documents.

Data on political, economic, cultural, religious, and social conditions spread over an enormous area circulated between the VOC establishments, the administrative centre of the trade in Batavia (modern-day Jakarta), and the board of directors (the Heeren XVII [nl]/Gentlemen Seventeen) in the Dutch Republic.