Filial piety

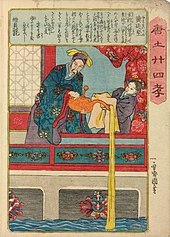

[citation needed] Filial piety is considered a key virtue in Chinese and other East Asian cultures, and it is the main subject of many stories.

[21] It is the fundamental principle of Confucian morality:[22] filial piety was seen as the basis for an orderly society, together with loyalty of the ministers toward the ruler, and servitude of the wife toward the husband.

[28] Care means making sure parents are comfortable in every single way: this involves food, accommodation, clothes, hygiene, and basically to have them "see and hear pleasurable things" (in Confucius' words)[29] and to have them live without worry.

[36] Nevertheless, filial piety mostly identified the child's duty, and in this, it differed from the Roman concept of patria potestas, which defined mostly the father's authoritative power.

[36][15] Jordan states that in classical Chinese thought, "remonstrance" was part of filial piety, meaning that a pious child needs to dissuade a parent from performing immoral actions.

[43] According to the Neo-Confucian philosopher Cheng Hao (1032–1085 CE), relationships and their corresponding roles "belong to the eternal principle of the cosmos from which there is no escape between heaven and earth".

[44] The idea of filial piety became popular in China because of the many functions it had and many roles it undertook, as the traditional Confucian scholars such as Mencius (4th century BCE) regarded the family as a fundamental unit that formed the root of the nation.

Though the virtue of xiào was about respect by children toward their parents, it was meant to regulate how the young generation behaved toward elders in the extended family and in society in general.

Mencius teaches that ministers should overthrow an immoral tyrant, should he harm the state; the loyalty to the king was considered conditional, not as unconditional as in filial piety towards one parents.

Yang defined it as a "specific, complex syndrome or set of cognition, affects, intentions, and behaviors concerning being good or nice to one's parents".

[64] Psychologists have found correlations[clarification needed] between filial piety and lower socio-economic status, female gender, elders, minorities, and non-westernized cultures.

Filial piety has also been related to[specify] an orientation to the past, resistance to cognitive change, superstition and fatalism, dogmatism, authoritarianism, conformism, a belief in the superiority of one's culture, and a lack of active, critical, and creative learning attitudes.

[65] Ho connects the value of filial piety with authoritarian moralism and cognitive conservatism in Chinese patterns of socialization, basing this on findings among subjects in Hong Kong and Taiwan.

Cognitive moralism he derives from social psychologist Anthony Greenwald, and is a "disposition to preserve existing knowledge structures" and resistance to change.

He concludes that filial piety appears to have a negative effect on psychological development, but at the same time, partly explains the high motivation of Chinese people to achieve academic results.

[69] Francis Hsu argued that pro-family attitudes informed by filial piety, when taken on the level of the family at large, can lead to nepotism and corruption, and are at tension with the good of the state as whole.

Texts such as the Classic of Changes (10th–4th century BCE) may contain early references to the parallel conception of the filial son and the loyal minister.

[27] Behavior regarded as unfilial such as mistreating or abandoning one's parents or grandparents, or refusing to complete the mourning period for them, was punished by exile and beating, or worse.

[30][79] The promotion of filial piety in this manner, as part of the idea of li, was a less confrontational way to create order in society than resorting to law.

[79] During the early Confucian period, the principles of filial piety were brought back by Japanese and Korean students to their respective homelands, where they became central to the education system.

Later scholarship, led by people such as John Strong and Gregory Schopen, has come to believe that filial piety was part of Buddhist doctrine since early times.

[94] Sun Chuo (c. 300–380) further argued that monks were working to ensure the salvation of all people and making their family proud by doing so,[94] and Liu Xie stated that Buddhists practiced filial piety by sharing merit with their departed relatives.

Huiyuan (334–416) responded that although monks did not express such piety, they did pay homage in heart and mind; moreover, their teaching of morality and virtue to the public helped support imperial rule.

[99][98] The Ullambana Sūtra introduced the idea of transfer of merit through the story of Mulian Saves His Mother and led to the establishment of the Ghost Festival.

[103] Nevertheless, although critics of Buddhism did not have much impact during this time, this changed in the period leading up to the Neo-Confucianist revival, when Emperor Wu Zong (841–845) started the Great Anti-Buddhist Persecution, citing lack of filial piety as one of his reasons for attacking Buddhist institutions.

In China, Buddhism continued to uphold a role in state rituals and mourning rites for ancestors until late imperial times (13th–20th century).

The duties of the obedient child were much more precisely and rigidly prescribed, to the extent that legal scholar Hsu Dau-lin argued about this period that it "engendered a highly authoritarian spirit which was entirely alien to Confucius himself".

The late imperial Chinese held patriarchalism high as an organizing principle of society, as laws and punishments gradually became more strict and severe.

[110] For this reason, China developed a more critical stance towards filial piety and other aspects of Confucianism than other East Asian countries, including not only Japan, but also Taiwan.

[6] As of 2009[update], care-giving of elderly people by the young had not undergone any revolutionary changes in the PRC, and family obligations still remained strong, "almost automatic".