Higgs boson

After a 40-year search, a subatomic particle with the expected properties was discovered in 2012 by the ATLAS and CMS experiments at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN near Geneva, Switzerland.

Similarly, measuring the speed of light in vacuum seems to give the identical result, whatever the location in time and space, and whatever the local gravitational field.

The importance of this fundamental question led to a 40-year search, and the construction of one of the world's most expensive and complex experimental facility to date, CERN's Large Hadron Collider (LHC),[28] in an attempt to create Higgs bosons and other particles for observation and study.

[29][31][7] The presence of the field, now confirmed by experimental investigation, explains why some fundamental particles have (a rest) mass, despite the symmetries controlling their interactions implying that they should be "massless".

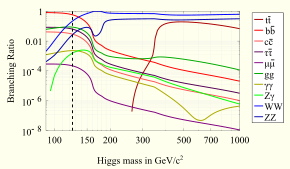

More studies are needed to verify with higher precision that the discovered particle has all of the properties predicted or whether, as described by some theories, multiple Higgs bosons exist.

Such theories are highly tentative and face significant problems related to unitarity, but may be viable if combined with additional features such as large non-minimal coupling, a Brans–Dicke scalar, or other "new" physics, and they have received treatments suggesting that Higgs inflation models are still of interest theoretically.

[l] If the masses of the Higgs boson and top quark are known more precisely, and the Standard Model provides an accurate description of particle physics up to extreme energies of the Planck scale, then it is possible to calculate whether the vacuum is stable or merely long-lived.

[55][n] It also suggests that the Higgs self-coupling λ and its βλ function could be very close to zero at the Planck scale, with "intriguing" implications, including theories of gravity and Higgs-based inflation.

The six authors of the 1964 PRL papers, who received the 2010 J. J. Sakurai Prize for their work; from left to right: Kibble, Guralnik, Hagen, Englert, Brout; right image: Higgs.

[24] These approaches were quickly developed into a full relativistic model, independently and almost simultaneously, by three groups of physicists: by François Englert and Robert Brout in August 1964;[69] by Peter Higgs in October 1964;[70] and by Gerald Guralnik, Carl Hagen, and Tom Kibble (GHK) in November 1964.

For example, Coleman found in a study that "essentially no-one paid any attention" to Weinberg's paper prior to 1971[85] and discussed by David Politzer in his 2004 Nobel speech.

[82][84] The resulting electroweak theory and Standard Model have accurately predicted (among other things) weak neutral currents, three bosons, the top and charm quarks, and with great precision, the mass and other properties of some of these.

[123][124] Using the combined analysis of two interaction types (known as 'channels'), both experiments independently reached a local significance of 5 sigma – implying that the probability of getting at least as strong a result by chance alone is less than one in three million.

[122] The two teams had been working 'blinded' from each other from around late 2011 or early 2012,[106] meaning they did not discuss their results with each other, providing additional certainty that any common finding was genuine validation of a particle.

[126] In November 2012, in a conference in Kyoto researchers said evidence gathered since July was falling into line with the basic Standard Model more than its alternatives, with a range of results for several interactions matching that theory's predictions.

[138] In early March 2013, CERN Research Director Sergio Bertolucci stated that confirming spin-0 was the major remaining requirement to determine whether the particle is at least some kind of Higgs boson.

On 14 March 2013 CERN confirmed the following: CMS and ATLAS have compared a number of options for the spin-parity of this particle, and these all prefer no spin and even parity [two fundamental criteria of a Higgs boson consistent with the Standard Model].

[146][147] The LHC's experimental work since restarting in 2015 has included probing the Higgs field and boson to a greater level of detail, and confirming whether less common predictions were correct.

[148][149][150] Gauge invariance is an important property of modern particle theories such as the Standard Model, partly due to its success in other areas of fundamental physics such as electromagnetism and the strong interaction (quantum chromodynamics).

(This can be seen by examining the Dirac Lagrangian for a fermion in terms of left and right handed components; we find none of the spin-half particles could ever flip helicity as required for mass, so they must be massless.

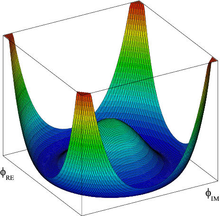

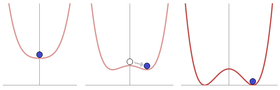

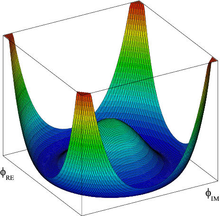

Below a certain extremely high energy level the existence of this non-zero vacuum expectation spontaneously breaks electroweak gauge symmetry which in turn gives rise to the Higgs mechanism and triggers the acquisition of mass by those particles interacting with the field.

The intractable problems of both underlying theories "neutralise" each other, and the residual outcome is that elementary particles acquire a consistent mass based on how strongly they interact with the Higgs field.

[v] While tachyons (particles that move faster than light) are a purely hypothetical concept, fields with imaginary mass have come to play an important role in modern physics.

[161][162] Under no circumstances do any excitations ever propagate faster than light in such theories – the presence or absence of a tachyonic mass has no effect whatsoever on the maximum velocity of signals (there is no violation of causality).

In the extreme energies of these collisions, the desired esoteric particles will occasionally be produced and this can be detected and studied; any absence or difference from theoretical expectations can also be used to improve the theory.

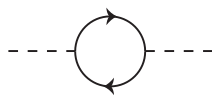

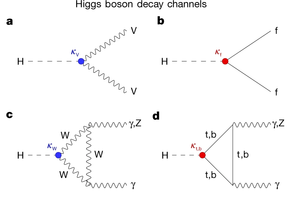

[2] However, this process is very relevant for experimental searches for the Higgs boson, because the energy and momentum of the photons can be measured very precisely, giving an accurate reconstruction of the mass of the decaying particle.

[199] While media use of this term may have contributed to wider awareness and interest,[200] many scientists feel the name is inappropriate[16][17][201] since it is sensational hyperbole and misleads readers;[202] the particle also has nothing to do with any God, leaves open numerous questions in fundamental physics, and does not explain the ultimate origin of the universe.

[205] Science writer Ian Sample stated in his 2010 book on the search that the nickname is "universally hate[d]" by physicists and perhaps the "worst derided" in the history of physics, but that (according to Lederman) the publisher rejected all titles mentioning "Higgs" as unimaginative and too unknown.

[206] Lederman begins with a review of the long human search for knowledge, and explains that his tongue-in-cheek title draws an analogy between the impact of the Higgs field on the fundamental symmetries at the Big Bang, and the apparent chaos of structures, particles, forces and interactions that resulted and shaped our present universe, with the biblical story of Babel in which the primordial single language of early Genesis was fragmented into many disparate languages and cultures.

But it is also incomplete and, in fact, internally inconsistent [...] This boson is so central to the state of physics today, so crucial to our final understanding of the structure of matter, yet so elusive, that I have given it a nickname: the God Particle.