Histone acetyltransferase

Research has emerged, since, to show that lysine acetylation and other posttranslational modifications of histones generate binding sites for specific protein–protein interaction domains, such as the acetyllysine-binding bromodomain[citation needed].

Histone acetyltransferases can also acetylate non-histone proteins, such as nuclear receptors and other transcription factors to facilitate gene expression.

[2] Type A HATs are located in the nucleus and are involved in the regulation of gene expression through acetylation of nucleosomal histones in the context of chromatin.

Type B HATs are located in the cytoplasm and are responsible for acetylating newly synthesized histones prior to their assembly into nucleosomes.

The acetyl groups added by type B HATs to the histones are removed by HDACs once they enter the nucleus and are incorporated into chromatin.

These HATs are typically characterized by the presence of zinc fingers and chromodomains, and they are found to acetylate lysine residues on histones H2A, H3, and H4.

Several MYST family proteins contain zinc fingers as well as the highly conserved motif A found among GNATs that facilitates acetyl-CoA binding.

In addition to those that are members of the GNAT and MYST families, there are several other proteins found typically in higher eukaryotes that exhibit HAT activity.

ACTR (also known as RAC3, AIB1, and TRAM-1 in humans) shares significant sequence homology with SRC-1, in particular in the N-terminal and C-terminal (HAT) regions as well as in the receptor and coactivator interaction domains.

A table summarizing the different families of HATs along with their associated members, parent organisms, multisubunit complexes, histone substrates, and structural features is presented below.

(nuclear receptor coactivators) In general, HATs are characterized by a structurally conserved core region made up of a three-stranded β-sheet followed by a long α-helix parallel to and spanning one side of it.

[7][8] The core region, which corresponds to motifs A, B, and D of the GNAT proteins,[4] is flanked on opposite sides by N- and C-terminal α/β segments that are structurally unique for a given HAT family.

Many MYST proteins also contain a cysteine-rich, zinc-binding domain within the HAT region in addition to an N-terminal chromodomain, which binds to methylated lysine residues.

On a broader scale, the structures of the catalytic domains of GNAT proteins (Gcn5, PCAF) exhibit a mixed α/β globular fold with a total of five α-helices and six β-strands.

In addition, the residues in the active site of each enzyme are distinct, which suggests that they employ different catalytic mechanisms for acetyl group transfer.

Members of the GNAT family have a conserved glutamate residue that acts as a general base for catalyzing the nucleophilic attack of the lysine amine on the acetyl-CoA thioester bond.

[8] These HATs use an ordered sequential bi-bi mechanism wherein both substrates (acetyl-CoA and histone) must bind to form a ternary complex with the enzyme before catalysis can occur.

[4][8] Studies of yeast Esa1 from the MYST family of HATs have revealed a ping-pong mechanism involving conserved glutamate and cysteine residues.

Then, a glutamate residue acts as a general base to facilitate transfer of the acetyl group from the cysteine to the histone substrate in a manner analogous to the mechanism used by GNATs.

In human p300, Tyr1467 acts as a general acid and Trp1436 helps orient the target lysine residue of the histone substrate into the active site.

[4][5] In flies, acetylation of H4K16 on the male X chromosome by MOF in the context of the MSL complex is correlated with transcriptional upregulation as a mechanism for dosage compensation in these organisms.

The idea that acetylation can affect protein function in this manner has led to inquiry regarding the role of acetyltransferases in signal transduction pathways and whether an appropriate analogy to kinases and phosphorylation events can be made in this respect.

In contrast, Gcn5 acquires the ability to acetylate multiple sites in both histones H2B and H3 when it joins other subunits to form the SAGA and ADA complexes.

[8] However, data suggests that associated subunits may contribute to catalysis at least in part by facilitating productive binding of the HAT complex to its native histone substrates.

[8] Human MOF as well as yeast Esa1 and Sas2 are autoacetylated at a conserved active site lysine residue, and this modification is required for their function in vivo.

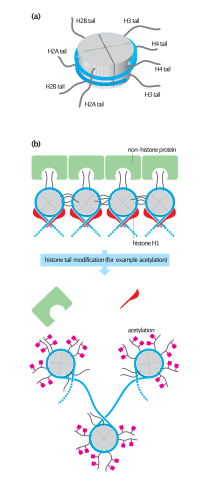

Acetylation is not the only regulatory post-translational modification to histones that dictates chromatin structure; methylation, phosphorylation, ADP-ribosylation, and ubiquitination have also been reported.

[29] The ability of histone acetyltransferases to manipulate chromatin structure and lay an epigenetic framework makes them essential in cell maintenance and survival.

The process of chromatin remodeling involves several enzymes, including HATs, that assist in the reformation of nucleosomes and are required for DNA damage repair systems to function.

The human premature aging syndrome Hutchinson Gilford progeria is caused by a mutational defect in the processing of lamin A, a nuclear matrix protein.

If garcinol is successful at inhibiting the process of non-homologous end joining, a DNA repair mechanism that shows preference in fixing double-strand breaks,[36] then it may serve as a radiosensitizer, a molecule that increases the sensitivity of cells to radiation damage.