Historic recurrence

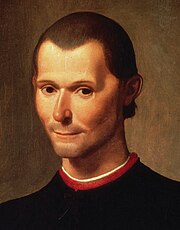

"[12] In the Islamic world, Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406) wrote that asabiyyah (social cohesion or group unity) plays an important role in a kingdom's or dynasty's cycle of rise and fall.

"[15] "Other minor cases of recurrence thinking", he writes, "include the isolation of any two specific events which bear a very striking similarity, and the preoccupation with parallelism, that is, with resemblances, both general and precise, between separate sets of historical phenomena" (emphasis in original).

[15] G. W. Trompf notes that most western concepts of historic recurrence imply that "the past teaches lessons for ... future action"—that "the same ... sorts of events which have happened before ... will recur".

[7] One such recurring theme was early offered by Poseidonius (a Greek polymath, native to Apamea, Syria; c. 135–51 BCE), who argued that dissipation of the old Roman virtues had followed the removal of the Carthaginian challenge to Rome's supremacy in the Mediterranean world.

In the case of each empire, growth had resulted from consolidation against an external enemy; Rome herself, in response to Hannibal's threat posed at Cannae, had risen to great-power status within a mere five decades.

With Rome's world dominion, however, aristocracy had been supplanted by a monarchy, which in turn tended to decay into tyranny; after Augustus Caesar, good rulers had alternated with tyrannical ones.

[24]In 1377, the Arab scholar Ibn Khaldun, in his Muqaddima (or Prolegomena), wrote that when nomadic tribes become united by asabiyya—Arabic for "group feeling", "social solidarity", or "clannism"—their superior cohesion and military prowess puts urban dwellers at their mercy.

The ruler, who can no longer rely on fierce warriors for his defense, will have to raise extortionate taxes to pay for other sorts of soldiers, and this in turn may lead to further problems that result in the eventual downfall of his dynasty or state.

[27] Sir Arthur Keith's theory of a species-wide amity-enmity complex suggests that human conscience evolved as a duality: people are driven to protect members of their in-group, and to hate and fight enemies who belong to an out-group.

[k] On 27 April 1521, Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan, in the Philippine Islands, foolhardily, with only four dozen men, confronted 1,500 natives who defied his attempt to Christianize them and was killed.

[44][m] Humans tend to behave in accordance with the principles of social physics described by the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes after he had met the Italian physicist Galileo Galilei in 1636 in Florence.

John Vaillant writes, in reference to the global-warming crisis, of "the self-protective tendency to favor the status quo over a potentially disruptive scenario one has not witnessed personally.

"[48] While it was clear from the laws of physics that rising levels of "greenhouse gases" in Earth's atmosphere must eventually cause disastrous climate warming, with consequently enhanced droughts, floods, forest fires, and cyclones,[49] people were easily lulled into complacency by the mendacities of fossil-fuel interests.

Similarly, navies continue building aircraft carriers, at enormous expense, despite their clear vulnerability to attack, because their construction creates civilian jobs and because, says Stephen Wrage, political science teacher at the U.S.

Ascendance, according to Amis, had passed to the United States, and Americans such as Saul Bellow, Norman Mailer, Philip Roth, and John Updike began writing huge novels.

[61] Gabriel García Márquez, in his novel The Autumn of the Patriarch (1975), ... create[d] a composite character: a mythical, unnamed autocrat who has held sway, seemingly forever, over an invented Caribbean country akin to Costaguana in Joseph Conrad's Nostromo.

To portray him, García Márquez drew upon a motley cohort of Latin American caudillos ... as well as Spain's Generalissimo Francisco Franco ...[62]Ruth Ben-Ghiat in Strongmen: Mussolini to the Present (2020), writes Ariel Dorfman, documents the "viral recurrence" around the world, over the past century, of despots and authoritarians "with comparable strategies of control and mendacity".

Ben-Ghiat divides the narrative into three – at times, overlapping – periods:[63] The era of fascist takeovers runs from 1919 and the ascent of Mussolini until Hitler's defeat in 1945, with Franco as the third member of this atrocious trio ... [In] the next phase, the age of military coups (1950–1990) [t]he main representatives ... are Pinochet, Muammar Qaddafi, and Mobutu Sese Seko, along with minor figures like Idi Amin, Saddam Hussein, and Mohamed Siad Barre.

Ben-Ghiat primarily dissects Silvio Berlusconi, Vladimir Putin, and Donald Trump, with Viktor Orbán, Jair Bolsonaro, Rodrigo Duterte, Narendra Modi, and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan given perfunctory assessments.

Nor is there mention of Indonesia's Suharto or the Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, "though the CIA engineered coups that led to both ... lording it over their lands, and the agency can also be linked to Pinochet's military putsch in Chile."

Some notable practitioners of political mendacity discussed by Mount include Julius Caesar, Cesare Borgia, Queen Elizabeth I, Oliver Cromwell, Robert Clive, Napoleon, Winston Churchill, Tony Blair, Boris Johnson, and Donald Trump.