History of the Netherlands

[18] A Frankish identity emerged in the lower and middle Rhine valley during the first half of the 3rd century, forming a confederation of smaller Germanic groups[19] including the descendants of the Batavian rebels.

It was a large, flourishing trading place, three kilometers long and situated where the rivers Rhine and Lek diverge southeast of Utrecht near the modern town of Wijk bij Duurstede.

After Roman government in the area collapsed, the Franks expanded their territories until there were numerous small Frankish kingdoms, especially at Cologne, Tournai, Le Mans and Cambrai.

[41] These Viking raids occurred about the same time that French and German lords were fighting for supremacy over the middle empire that included the Netherlands, so their sway over this area was weak.

In addition to the growing independence of the towns, local rulers turned their counties and duchies into private kingdoms and felt little sense of obligation to the emperor who reigned over large parts of the nation in name only.

A common theory states that Frankish migration from either Flanders, Utrecht or both displaced the Frisians in Holland, however no evidence has been found in support of this theory and more recent studies have suggested that Frisians from the mouth of the Rhine adopted the Franconian language, feudal system and religion,[42][43][44] spreading this new 'Hollandic' identity northward over the centuries (the part of North Holland situated north of Alkmaar is still colloquially known as West Friesland).

By the early 11th century, Dirk III, Count of Holland was levying tolls on the Meuse estuary and was able to resist military intervention from his overlord, the Duke of Lower Lorraine.

Before that, towns were built north of the major rivers, Utrecht, Kampen, Deventer, Zwolle, Nijmegen, and Zutphen, but with the expansion of dikes and drainage, cultivable land was created and population expanded.

On the other hand, the intensely moralistic Dutch Protestants insisted their Biblical theology, sincere piety and humble lifestyle was morally superior to the luxurious habits and superficial religiosity of the ecclesiastical nobility.

[63] Alba then revoked all the prior treaties that Margaret, the Duchess of Parma had signed with the Protestants of the Netherlands and instituted the Inquisition to enforce the decrees of the Council of Trent.

His strategy was to offer generous terms for the surrender of a city: there would be no more massacres or looting; historic urban privileges were retained; there was a full pardon and amnesty; return to the Catholic Church would be gradual.

New Netherland was slowly settled during its first decades, partially as a result of policy mismanagement by the Dutch West India Company (WIC), and conflicts with Native Americans.

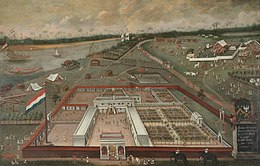

It had many world firsts—the first multinational corporation, the first company to issue stock, and the first megacorporation, possessing quasi-governmental powers, including the ability to wage war, negotiate treaties, coin money, and establish colonial settlements.

The VOC, one of the major European trading houses sailing the spice route to East Asia, had no intention of colonizing the area, instead wanting only to establish a secure base camp where passing ships could shelter, and where hungry sailors could stock up on fresh supplies of meat, fruit, and vegetables.

[85] Some free burghers continued to expand into the rugged hinterlands of the north and east, many began to take up a semi-nomadic pastoralist lifestyle, in some ways not far removed from that of the Khoikhoi they had displaced.

These were the first of the Trekboers (Wandering Farmers, later shortened to Boers), completely independent of official controls, extraordinarily self-sufficient, and isolated from the government and the main settlement in Cape Town.

Despised by his co-villagers and forced to subsist on the gleanings of the peasants, he combined drumming the catechism into the heads of his unruly charges with the duties of winding the town clock, ringing the church bells or digging its graves.

His principal use to the community was to keep its boys out of mischief when there was no labour for them in the fields, or setting the destitute orphans of the town to the 'useful arts' of picking tow or spinning crude flax.

This entirely overthrew the old order of things in the southern Netherlands: it abolished the privileges of the Catholic Church, and guaranteed equal protection to every religious creed and the enjoyment of the same civil and political rights to every subject of the king.

Other factors that contributed to this feeling were economic (the South was industrialising, the North had always been a merchants' nation) and linguistic (French was spoken in Wallonia and a large part of the bourgeoisie in Flemish cities).

They included the abolition of internal tariffs and guilds, a unified coinage system, modern methods of tax collection, standardized weights and measures, and the building of many roads, canals, and railroads.

The number of people employed in agriculture decreased, while the country made a strong effort to revive its stake in the highly competitive shipping and trade business.

After the harassment ended in the 1850s, a number of these dissidents eventually created the Christian Reformed Church in 1869; thousands migrated to Michigan, Illinois, and Iowa in the United States.

Dutch social and political life became divided by fairly clear-cut internal borders that were emerging as the society pillarized into three separate parts based on religion.

The members of different zuilen lived in close proximity in cities and villages, spoke the same language, and did business with one another, but seldom interacted informally and rarely intermarried.

Pillarization was officially recognized in the Pacification of 1917, whereby socialists and liberals achieved their goal of universal male suffrage and the religious parties were guaranteed equal funding of all schools.

A representative leader of science was Johannes Diderik van der Waals (1837–1923), a working class youth who taught himself physics, earned a PhD at the nation's leading school Leiden University, and in 1910 won the Nobel Prize for his discoveries in thermodynamics.

Its occasional messages serve an international community with diverse methodological approaches, archival experiences, teaching styles, and intellectual traditions, promotes discussion relevant to the region and to the different national histories in particular, with an emphasis on the Netherlands.

While agreeing that the intellectual milieus of late 19th and 20th centuries affected historians' interpretations, Cruz argued that writings about the revolt trace changing perceptions of the role played by small countries in the history of Europe.

He concluded that a serious crisis occurred in European civilization in 1900 because of the rise of anti-Semitism, extreme nationalism, discontent with the parliamentary system, depersonalization of the state, and the rejection of positivism.

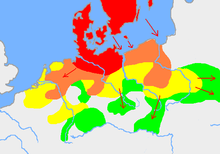

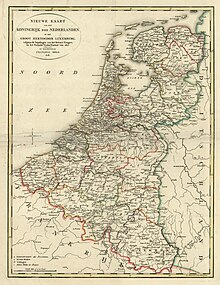

1 , 2 and 3 United Kingdom of the Netherlands (until 1830)

1 and 2 Kingdom of the Netherlands (after 1839)

2 Duchy of Limburg (1839–1867) (in the German Confederacy after 1839 as compensation for Waals-Luxemburg)

3 and 4 Kingdom of Belgium (after 1839)

4 and 5 Grand Duchy of Luxembourg (borders until 1839)

4 Province of Luxembourg (Waals-Luxemburg, to Belgium in 1839)

5 Grand Duchy of Luxembourg (German Luxemburg; borders after 1839)

In blue, the borders of the German Confederation .