History of Detroit

They were joined by traders from Montreal and Quebec; all had to contend with the powerful Five Nations of the League of the Iroquois (Haudenosaunee), who took control of the southern shores of Lakes Erie and Huron through the Beaver Wars of the 17th century.

Immigration grew initially for the lucrative inland and Great Lakes connected fur trade, based on continuing relations with influential Native American chiefs and interpreters.

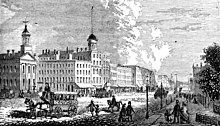

After Detroit rebuilt in the early 19th century, a thriving community soon sprang up, and by the Civil War, over 45,000 people were living in the city,[23] primarily spread along Jefferson Avenue to the east and Fort Street to the west.

In addition to attracting the best workers in Detroit, Ford's high wage policy effectively stopped the massive turnover rate, raised productivity, lowered overall labor costs and helped to propel the Model T to industry dominance.

At this time, the hardships of life in the Jim Crow South and the promise of manufacturing jobs in the North brought African Americans to Detroit in large numbers in the Great Migration.

Supported by Detroit's business, professional, and Protestant religious communities, the League campaigned for a new city charter, an anti-saloon ordinance, and the open shop whereby a worker could get a job even if he did not belong to a labor union.

Although many people began to pile into Detroit, Thomas Sugrue, author of "The Origins of the Urban Crisis", suggests, "Beginning in the 1920s—and certainly by the 1940s—class and race became more important than ethnicity as a guide to the city's residential geography."

It expanded its borders exponentially by annexing all or part of the incorporated villages of Woodmere (1905), Delray (1905), Fairview (1907), St. Clair Heights (1918), and Warrendale (1925), as well as thousands of acres of land in the surrounding townships.

This changed after 1910 as the old-stock Protestant business leaders, especially from the automobile industry, led a Progressive Era crusade for efficiency, and elected their own men to office, typified by James J. Couzens (mayor, 1919–1922, US Senator, 1922–1936).

[75] The anti public-housing movement appropriated World War II rhetoric to denounce public housing as a communist conspiracy, a catalyst of racial struggle that would "destroy traditional American values".

The United States preached the gospel of freedom and human rights abroad while discriminatory federal policy, executed by a racist city government, robbed Black Detroiters of safe and affordable housing.

a large well-paid middle class black community emerged; like their white counterparts, they wanted to own single family homes, fought for respectability, and left the blight and crime of the slums as fast as possible for outlying districts and suburbs.

Detroit played a major role in the civil rights movement of the 1960s; the Model Cities Program was a key component of President Lyndon B. Johnson's Great Society and War on Poverty.

Highly controversial was his using eminent domain to purchase and raze a 465-acre inner-city neighborhood known as Poletown that was home to 3,500 people, mostly Polish property owners, in order to make way for a half-billion-dollar General Motors Cadillac assembly plant.

The closed auto plants were also often abandoned in a period before strong environmental regulation, causing the sites to become so-called "brownfields", unattractive to potential replacement businesses because of the pollution hangover from decades of industrial production.

[125] The mass migration of hopeful blacks from the Jim Crow-perpetuated racism and segregation of the South into Northern neighborhoods coupled with sluggish housing construction flooded Detroit with overpopulation, limited funding, and residential mistreatment.

In particular, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) and the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) effectively marked the racial boundaries of Detroit to determine the actuarial soundness of urban neighborhoods.

[132] By preventing black from the ability to attain mortgage loans from local banks, the New Deal private-public partnerships used redlining to protect the property values and investment opportunities for white middle-class homes.

Colorblind universalism within Detroit's housing market remained a far-fetched aspiration of Black families in their pursuit of homeownership as FHA-HUD policy failed to dismantle the segregative impulses of the real estate industry.

[139] Coupled with the ability of de jure discrimination to mandate residential segregation through policy, neighborhood associations curbed civil rights reform that sought to mitigate racism within housing.

The middle-class mentality of neighborhood associations would govern the political climate of Detroit as this anti-integration constituency resonated with politicians who would dispel public housing and the threat of racial invasion.

The 1949 mayoral election of Detroit pitted George Edwards, a UAW activist and public housing advocate, against Albert Cobo, a corporate executive and real estate investor.

Factors were a combination of changes in technology, increased automation, auto industry consolidation, taxation policies, the need for different kinds of manufacturing space, and the highway system construction that eased commuter transportation.

[146] Perceptions of "urban blight" and a need for "slum clearance" in these areas were fueled especially by (majority white) Detroit city planners, who classified over two-thirds of housing in Paradise Valley as substandard.

[149] Local government officials popularized the push for urban renewal in post-World War II Detroit in conjunction with real estate agents and bank owners, who stood to gain from investment in new buildings and wealthier residents.

The Oakland-Hastings Freeway, now called the I-375 Chrysler Highway, was laid directly along Hastings Street at the heart of the Black Bottom business district, and cut through the Lower East Side and Paradise Valley.

[160] In the aftermath of the riot, the Greater Detroit Board of Commerce launched a campaign to find jobs for ten thousand "previously unemployable" persons, a preponderant number of whom were black.

[219] Public transportation within the Downtown area has also been a target for private investors, as evidenced by Quicken Loans' investment in Detroit's QLine railcar, which currently runs a 3.3 miles (5.3 km) track along Woodward Avenue.

[232] Most CLTs are not built upon economically self-sustaining models, so they are forced to compete for external funding, taking away the CLT's autonomy, as all of the power is transferred into the hands of grant-funding organizations and private foundations.

[236] The city has hosted major sporting events—the 2005 MLB All-Star Game, 2006 Super Bowl XL, 2006 World Series, WrestleMania 23 in 2007 and the NCAA Final Four in April 2009—all of which prompted many improvements to the area.